Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles to settle in place. The particles that form a sedimentary rock are called sediment, and may be composed of geological detritus (minerals) or biological detritus. The geological detritus originated from weathering and erosion of existing rocks, or from the solidification of molten lava blobs erupted by volcanoes. The geological detritus is transported to the place of deposition by water, wind, ice or mass movement, which are called agents of denudation. Biological detritus was formed by bodies and parts of dead aquatic organisms, as well as their fecal mass, suspended in water and slowly piling up on the floor of water bodies. Sedimentation may also occur as dissolved minerals precipitate from water solution.

Till or glacial till is unsorted glacial sediment.

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand and silt can be carried in suspension in river water and on reaching the sea bed deposited by sedimentation; if buried, they may eventually become sandstone and siltstone through lithification.

An alluvial fan is an accumulation of sediments that fans outwards from a concentrated source of sediments, such as a narrow canyon emerging from an escarpment. They are characteristic of mountainous terrain in arid to semiarid climates, but are also found in more humid environments subject to intense rainfall and in areas of modern glaciation. They range in area from less than 1 square kilometer (0.4 sq mi) to almost 20,000 square kilometers (7,700 sq mi).

Conglomerate is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed of a substantial fraction of rounded to subangular gravel-size clasts. A conglomerate typically contains a matrix of finer-grained sediments, such as sand, silt, or clay, which fills the interstices between the clasts. The clasts and matrix are typically cemented by calcium carbonate, iron oxide, silica, or hardened clay.

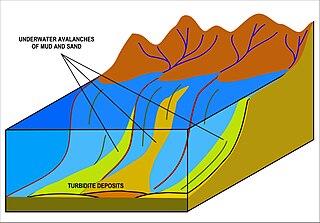

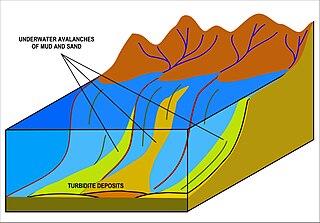

A turbidite is the geologic deposit of a turbidity current, which is a type of amalgamation of fluidal and sediment gravity flow responsible for distributing vast amounts of clastic sediment into the deep ocean.

Diamicton is a terrigenous sediment that is unsorted to poorly sorted and contains particles ranging in size from clay to boulders, suspended in an unconsolidated matrix of mud or sand. Today, the word has strong connotations to glaciation but can be used in a variety of geological settings.

Boulder clay is an unsorted agglomeration of clastic sediment that is unstratified and structureless and contains gravel of various sizes, shapes, and compositions distributed at random in a fine-grained matrix. The fine-grained matrix consists of stiff, hard, pulverized clay or rock flour. Boulder clay is also known as either known as drift clay; till; unstratified drift, geschiebelehm (German); argile á blocaux (French); and keileem (Dutch).

Mudrocks are a class of fine-grained siliciclastic sedimentary rocks. The varying types of mudrocks include siltstone, claystone, mudstone, slate, and shale. Most of the particles of which the stone is composed are less than 1⁄16 mm and are too small to study readily in the field. At first sight, the rock types appear quite similar; however, there are important differences in composition and nomenclature.

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus, chunks, and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks by physical weathering. Geologists use the term clastic to refer to sedimentary rocks and particles in sediment transport, whether in suspension or as bed load, and in sediment deposits.

Debris flows are geological phenomena in which water-laden masses of soil and fragmented rock rush down mountainsides, funnel into stream channels, entrain objects in their paths, and form thick, muddy deposits on valley floors. They generally have bulk densities comparable to those of rock avalanches and other types of landslides, but owing to widespread sediment liquefaction caused by high pore-fluid pressures, they can flow almost as fluidly as water. Debris flows descending steep channels commonly attain speeds that surpass 10 m/s (36 km/h), although some large flows can reach speeds that are much greater. Debris flows with volumes ranging up to about 100,000 cubic meters occur frequently in mountainous regions worldwide. The largest prehistoric flows have had volumes exceeding 1 billion cubic meters. As a result of their high sediment concentrations and mobility, debris flows can be very destructive.

The Roxbury Conglomerate, also informally known as Roxbury puddingstone, is a name for a rock formation that forms the bedrock underlying most of Roxbury, Massachusetts, now part of the city of Boston. The bedrock formation extends well beyond the limits of Roxbury, underlying part or all of Quincy, Canton, Milton, Dorchester, Dedham, Jamaica Plain, Brighton, Brookline, Newton, Needham, and Dover. It is named for exposures in Roxbury, Boston area.

In geology, a graded bed is one characterized by a systematic change in grain or clast size from one side of the bed to the other. Most commonly this takes the form of normal grading, with coarser sediments at the base, which grade upward into progressively finer ones. Such a bed is also described as fining upward. Normally graded beds generally represent depositional environments which decrease in transport energy as time passes, but these beds can also form during rapid depositional events. They are perhaps best represented in turbidite strata, where they indicate a sudden strong current that deposits heavy, coarse sediments first, with finer ones following as the current weakens. They can also form in terrestrial stream deposits.

A subaqueous fan is a fan-shaped deposit formed beneath water, and are commonly related to glaciers and crater lakes.

Stratigraphic cycles refer to the transgressive and regressive sequences bounded by unconformities in the stratagraphic record on the cratons. These cycles represent a large scale eustasy cycle since the Cambrian period with further sub-divisions of those units.

Marine sediment, or ocean sediment, or seafloor sediment, are deposits of insoluble particles that have accumulated on the seafloor. These particles have their origins in soil and rocks and have been transported from the land to the sea, mainly by rivers but also by dust carried by wind and by the flow of glaciers into the sea. Additional deposits come from marine organisms and chemical precipitation in seawater, as well as from underwater volcanoes and meteorite debris.

This glossary of geology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to geology, its sub-disciplines, and related fields. For other terms related to the Earth sciences, see Glossary of geography terms.

Submarine landslides are marine landslides that transport sediment across the continental shelf and into the deep ocean. A submarine landslide is initiated when the downwards driving stress exceeds the resisting stress of the seafloor slope material, causing movements along one or more concave to planar rupture surfaces. Submarine landslides take place in a variety of different settings, including planes as low as 1°, and can cause significant damage to both life and property. Recent advances have been made in understanding the nature and processes of submarine landslides through the use of sidescan sonar and other seafloor mapping technology.

Hemipelagic sediment, or hemipelagite, is a type of marine sediment that consists of clay and silt-sized grains that are terrigenous and some biogenic material derived from the landmass nearest the deposits or from organisms living in the water. Hemipelagic sediments are deposited on continental shelves and continental rises, and differ from pelagic sediment compositionally. Pelagic sediment is composed of primarily biogenic material from organisms living in the water column or on the seafloor and contains little to no terrigenous material. Terrigenous material includes minerals from the lithosphere like feldspar or quartz. Volcanism on land, wind blown sediments as well as particulates discharged from rivers can contribute to Hemipelagic deposits. These deposits can be used to qualify climatic changes and identify changes in sediment provenances.

The Bransfield Basin is a back-arc rift basin located off the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. The basin lies within a Northeast and Southwest trending strait that separates the peninsula from the nearby South Shetland Islands to the Northwest. The basin extends for more than 500 kilometres from Smith Island to a portion of the Hero Fracture Zone. The basin can be subdivided into three basins: Western, Central, and Eastern. The Western basin is 130 kilometres long by 70 kilometres wide with a depth of 1.3 kilometres, the Central basin is 230 kilometres long by 60 kilometres wide with a depth of 1.9 kilometres, and the Eastern basin is 150 kilometres long by 40 kilometres wide with a depth of over 2.7 kilometres. The three basins are separated by the Deception Island and Bridgeman Island. The moho depth in the region has been seismically interpreted to be roughly 34 kilometres deep.