Mahavira, also known as Vardhamana, was the founder of Jainism and the 24th Tirthankara. He was the spiritual successor of the 23rd Tirthankara Parshvanatha. Mahavira was born in the early 6th century BCE to a royal Jain family of ancient India. His mother's name was Trishala and his father's name was Siddhartha. They were lay devotees of Parshvanatha. Mahavira abandoned all worldly possessions at the age of about 30 and left home in pursuit of spiritual awakening, becoming an ascetic. Mahavira practiced intense meditation and severe austerities for twelve and a half years, after which he attained Kevala Jnana (omniscience). He preached for 30 years and attained moksha (liberation) in the 6th century BCE, although the year varies by sect.

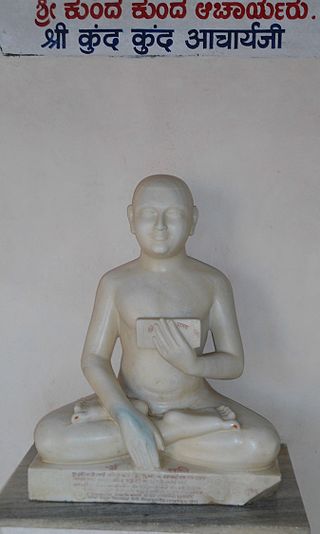

Acharya Virasena, also known as Veerasena, was a Digambara monk and belonged to the lineage of Acharya Kundakunda. He was an Indian mathematician and Jain philosopher and scholar. He was also known as a famous orator and an accomplished poet. His most reputed work is the Jain treatise Dhavala. The late Dr. Hiralal Jain places the completion of this treatise in 816 AD.

Ādi purāṇa is a 9th-century CE Sanskrit poem composed by Jinasena, a Digambara monk. It deals with the life of Rishabhanatha, the first Tirthankara.

Amoghavarsha I was the greatest emperor of the Rashtrakuta dynasty, and one of the most notable monarchs of Early Medieval India. His reign of 64 years is one of the longest precisely dated monarchical reigns on record. Many Kannada and Sanskrit scholars prospered during his rule, including the great Indian mathematician Mahaviracharya who wrote Ganita-sara-samgraha, Jinasena, Virasena, Shakatayan and Sri Vijaya.

Ācārya Bhadrabāhu was, according to both the Śvetāmbara and Digambara sects of Jainism, the last Shruta Kevalin in Jainism.

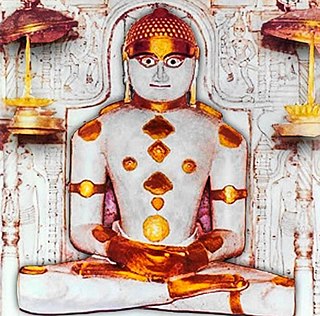

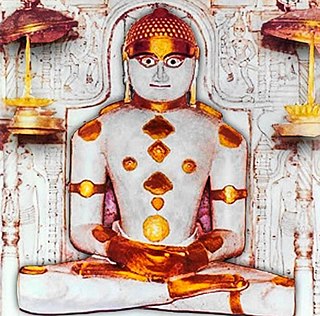

Rishabhanatha, also Rishabhadeva, Rishabha or Ikshvaku, is the first tirthankara of Jainism. He was the first of twenty-four teachers in the present half-cycle of time in Jain cosmology, and called a "ford maker" because his teachings helped one cross the sea of interminable rebirths and deaths. The legends depict him as having lived millions of years ago. He was the spiritual successor of Sampratti Bhagwan, the last Tirthankara of previous time cycle. He is also known as Ādinātha, as well as Adishvara, Yugadideva, Prathamarajeshwara and Nabheya. He is also known as Ikshvaku, establisher of the Ikshvaku dynasty. Along with Mahavira, Parshvanath, Neminath, and Shantinath, Rishabhanatha is one of the five Tirthankaras that attract the most devotional worship among the Jains.

Nemināth, also known as Nemi and Ariṣṭanemi, is the twenty-second tirthankara of Jainism in the present age. Neminath lived 81,000 years before the 23rd Tirthankar Parshvanath. According to traditional accounts, he was born to King Samudravijaya and Queen Shivadevi of the Yadu dynasty in the north Indian city of Sauripura. His birth date was the fifth day of Shravan Shukla of the Jain calendar. Krishna, who was the 9th and last Jain Vasudev, was his first cousin.

Mahapurana (महापुराण) or Trishashthilkshana Mahapurana is a major Jain text composed largely by Acharya Jinasena during the rule of Rashtrakuta ruler Amoghavarsha and completed by his pupil Gunabhadra in the 9th century CE. Mahapurana consists of two parts. The first part is Ādi purāṇa written by Acharya Jinasena in Sanskrit. The second part is Uttarapurana which is the section composed by Gunabhadra in Apabhraṃśa.

Rashtrakuta literature is the body of work created during the rule of the Rastrakutas of Manyakheta, a dynasty that ruled the southern and central parts of the Deccan, India between the 8th and 10th centuries. The period of their rule was an important time in the history of South Indian literature in general and Kannada literature in particular. This era was practically the end of classical Prakrit and Sanskrit writings when a whole wealth of topics were available to be written in Kannada. Some of Kannada's most famous poets graced the courts of the Rashtrakuta kings. Court poets and royalty created eminent works in Kannada and Sanskrit, that spanned such literary forms as prose, poetry, rhetoric, epics and grammar. Famous scholars even wrote on secular subjects such as mathematics. Rashtrakuta inscriptions were also written in expressive and poetic Kannada and Sanskrit, rather than plain documentary prose.

Kashtha Sangha was a Digambar Jain monastic order once dominant in several regions of North and Western India. It is considered to be a branch of Mula Sangh itself. It is said to have originated from a town named Kashtha.

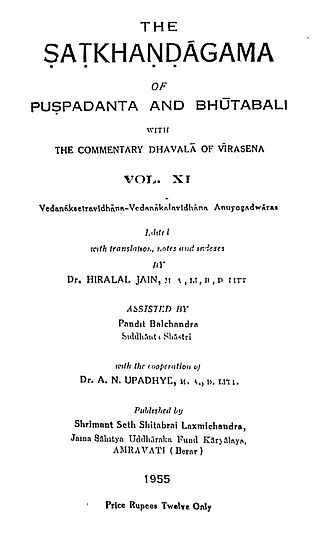

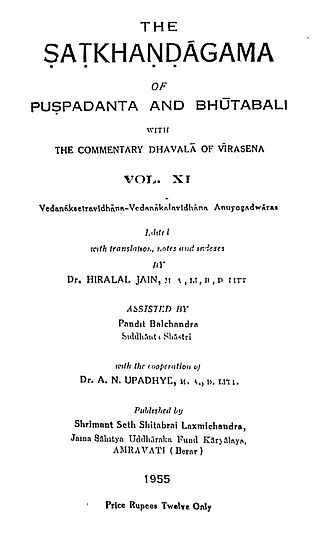

The Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama is the foremost and oldest Digambara Jain sacred text. According to Digambara tradition, the original teachings of lord Mahavira were passed on orally from Ganadhar, the chief disciple of Mahavira to his disciples and so on as they had the capability of listening and remembering it for always. But as the centuries passed there was downfall in these capabilities and so Ācārya Puṣpadanta and Bhūtabali penned down the teachings of Mahavira in Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama. Therefore the Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama is the most revered Digambara text that has been given the status of āgama.

Acharya Pujyapada or Pūjyapāda was a renowned grammarian and acharya belonging to the Digambara tradition of Jains. It was believed that he was worshiped by demigods on the account of his vast scholarship and deep piety, and thus, he was named Pujyapada. He was said to be the guru of King Durvinita of the Western Ganga dynasty.

Jainism is an ancient Indian religion belonging to the śramaṇa tradition. It prescribes ahimsa (non-violence) towards all living beings to the greatest possible extent. The three main teachings of Jainism are ahimsa, anekantavada (non-absolutism), aparigraha (non-possessiveness). Followers of Jainism take five main vows: ahimsa, satya, asteya, brahmacharya (chastity), and aparigraha. Monks follow them completely whereas śrāvakas (householders) observe them partially. Self-discipline and asceticism are thus major focuses of Jainism.

Jain literature refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the canonical Jain Agamas, which are written in Ardhamagadhi, a Prakrit language. Various commentaries were written on these canonical texts by later Jain monks. Later works were also written in other languages, like Sanskrit and Maharashtri Prakrit.

According to the Jain cosmology, the Śalākāpuruṣa "illustrious or worthy persons" are 63 illustrious beings who appear during each half-time cycle. They are also known as the triṣaṣṭiśalākāpuruṣa. The Jain universal or legendary history is a compilation of the deeds of these illustrious persons. Their life stories are said to be most inspiring.

Digambara is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being Śvetāmbara (white-clad). The Sanskrit word Digambara means "sky-clad", referring to their traditional monastic practice of neither possessing nor wearing any clothes.

Acharya Ravisena was a seventh century Digambara Jain Acharya, who wrote Padmapurana in Sanskrit in 678 AD. In Padmapurana, he mentions about a ceremony called suttakantha, which means the thread hanging from neck.

Samantabhadra was a Digambara acharya who lived about the later part of the second century CE. He was a proponent of the Jaina doctrine of Anekantavada. The Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra is the most popular work of Samantabhadra. Samantabhadra lived after Umaswami but before Pujyapada.

Guņabhadra was a Digambara monk in India. He co-authored Mahapurana along with Jinasena.

Uttarapurāṇa is a Jain text composed by Acharya Gunabhadra in the 9th century CE. According to the Digambara Uttarapurana text, Mahavira was born in Kundpur in the Kingdom of the Videhas.