Modoc County is a county located in the far northeast corner of the U.S. state of California. Its population is 8,700 as of the 2020 census, down from 9,686 from the 2010 census. This makes it California's third-least-populous county. The county seat and only incorporated city is Alturas. Previous County seats include Lake City and Centerville. The county borders Nevada and Oregon. Much of Modoc County is federal land. Several federal agencies, including the United States Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, have employees assigned to the area, and their operations are a significant part of its economy and services. The county's official slogans include "The last best place" and "Where the West still lives".

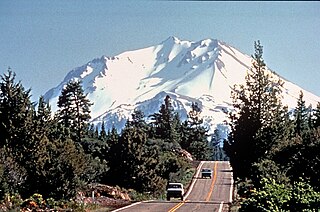

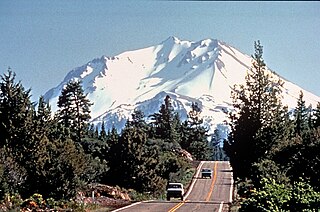

Siskiyou County is a county located in the northwestern portion of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 44,076. Its county seat is Yreka and its highest point is Mount Shasta. It falls within the Cascadia bioregion.

Lava Beds National Monument is located in northeastern California, in Siskiyou and Modoc counties. The monument lies on the northeastern flank of Medicine Lake Volcano, which is the largest volcano by area in the Cascade Range.

Ahjumawi Lava Springs State Park is a state park of California in the United States. It is located in remote northeastern Shasta County and is only accessible to the public by boat.

The Modoc War, or the Modoc Campaign, was an armed conflict between the Native American Modoc people and the United States Army in northeastern California and southeastern Oregon from 1872 to 1873. Eadweard Muybridge photographed the early part of the US Army's campaign.

The Modoc are an Indigenous American people who historically lived in the area which is now northeastern California and central Southern Oregon. Currently, they include two federally recognized tribes, the Klamath Tribes in Oregon and the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma, now known as the Modoc Nation.

The Battle of Lost River in November 1872 was the first battle in the Modoc War in the northwestern United States. The skirmish, which was fought near the Lost River along the California–Oregon border, was the result of an attempt by the U.S. 1st Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army to force a band of the Modoc tribe to relocate back to the Klamath Reservation, which they had left in objection of its conditions.

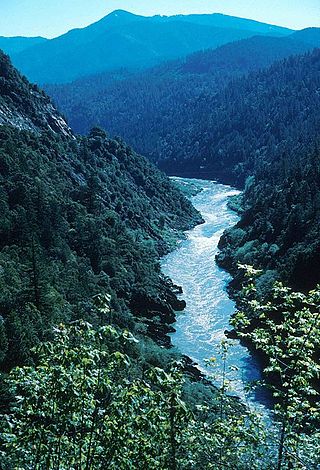

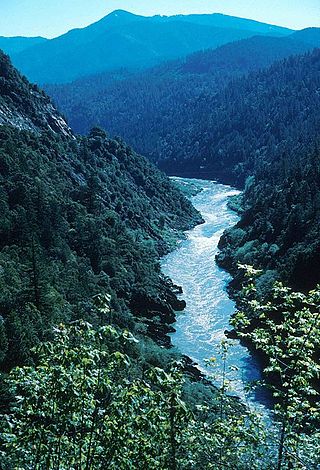

The Klamath River is a 257-mile (414 km) long river in southern Oregon and northern California. Beginning near Klamath Falls in the Oregon high desert, it flows west through the Cascade Range and Klamath Mountains before reaching the temperate rainforest of California's North Coast, where it empties into the Pacific Ocean. The Klamath River is the third-largest salmon and steelhead producing river on the west coast of the contiguous United States. The river's watershed – the Klamath Basin – encompasses more than 15,000 square miles (39,000 km2), and is known for its biodiverse forests, large areas of designated wilderness, and freshwater marshes that provide key migratory bird habitat.

Upper Klamath Lake is a large, shallow freshwater lake east of the Cascade Range in south-central Oregon in the United States. The largest body of fresh water by surface area in Oregon, it is approximately 25 miles (40 km) long and 8 miles (13 km) wide and extends northwest from the city of Klamath Falls. It sits at an average elevation of 4,140 feet (1,260 m).

The Williamson River of south-central Oregon in the United States is about 100 miles (160 km) long. It drains about 3,000 square miles (7,800 km2) east of the Cascade Range. Together with its principal tributary, the Sprague River, it provides over half the inflow to Upper Klamath Lake, the largest freshwater lake in Oregon. The lake's outlet is the Link River, which flows into Lake Ewauna and the Klamath River.

Lost River begins and ends in a closed basin in northern California and southern Oregon in the United States. The river, 60 miles (97 km) long, flows in an arc from Clear Lake Reservoir in Modoc County, California, through Klamath County, Oregon, to Tule Lake in Siskiyou County, California. About 46 mi (74 km) of Lost River are in Oregon, and 14 miles (23 km) are in California.

Goose Lake is a large alkaline lake in the Goose Lake Valley on the Oregon–California border in the United States. Like many other lakes in the Great Basin, it is a pluvial lake that formed from precipitation and melting glaciers during the Pleistocene epoch. The north portion of the lake is in Lake County, Oregon, and the south portion is in Modoc County, California. The mountains at the north end of the lake are part of the Fremont National Forest, and the south end of the lake is adjacent to Modoc National Forest lands. Most of the valley property around the lake is privately owned agricultural land, though Goose Lake State Recreation Area is on the Oregon side of the lake.

The Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway is a scenic byway and All-American Road in the U.S. states of California and Oregon. It is roughly 500 miles (800 km) long and travels north–south along the Cascade Range past numerous volcanoes. It is composed of two separate National Scenic Byways, the Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway - Oregon and Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway - California. The former includes Rim Drive within Crater Lake National Park, while the latter wholly includes the Lassen Scenic Byway within Lassen Volcanic National Park.

Tule Lake is an intermittent lake covering an area of 13,000 acres (53 km2), 8.0 km (5.0 mi) long and 4.8 km (3.0 mi) across, in northeastern Siskiyou County and northwestern Modoc County in California, along the border with Oregon.

The Klamath Basin is the region in the U.S. states of Oregon and California drained by the Klamath River. It contains most of Klamath County and parts of Lake and Jackson counties in Oregon, and parts of Del Norte, Humboldt, Modoc, Siskiyou, and Trinity counties in California. The 15,751-square-mile (40,790 km2) drainage basin is 35% in Oregon and 65% in California. In Oregon, the watershed typically lies east of the Cascade Range, while California contains most of the river's segment that passes through the mountains. In the Oregon-far northern California segment of the river, the watershed is semi-desert at lower elevations and dry alpine in the upper elevations. In the western part of the basin, in California, however, the climate is more of temperate rainforest, and the Trinity River watershed consists of a more typical alpine climate.

Lake Mojave is an ancient former lake fed by the Mojave River that, through the Holocene, occupied the Silver Lake and Soda Lake basins in the Mojave Desert of San Bernardino County, California. Its outlet may have ultimately emptied into the Colorado River north of Blythe.

Lake Manix is a former lake fed by the Mojave River in the Mojave Desert. It lies within San Bernardino County, California. Located close to Barstow, this lake had the shape of a cloverleaf and covered four basins named Coyote, Cady/Manix, Troy and Afton. It covered a surface area of 236 square kilometres (91 sq mi) and reached an altitude of 543 metres (1,781 ft) at highstands, although poorly recognizable shorelines have been found at altitudes of 547–558 metres (1,795–1,831 ft). The lake was fed by increased runoff during the Pleistocene and overflowed into the Lake Mojave basin and from there to Lake Manly in Death Valley, or less likely into the Bristol Lake basin and from there to the Colorado River.

Lake Corcoran was an ancient lake that covered the Central Valley of California.

Archeological Site 4-SK-4, nearest to Dorris, California, is a stratified archeological site that was a hunter-gatherer village west of Lower Klamath Lake. The site is located in the heart of the Klamath Basin wetlands, on the west shores of Sheepy Lake at Sheepy Creek. It has also been known as Nightfire Island and as Sheepy Island. Modern Modocs have called the island Shapasheni, meaning "where the sun and moon live", or "home of the sun and the moon.

The geology of California is highly complex, with numerous mountain ranges, substantial faulting and tectonic activity, rich natural resources and a history of both ancient and comparatively recent intense geological activity. The area formed as a series of small island arcs, deep-ocean sediments and mafic oceanic crust accreted to the western edge of North America, producing a series of deep basins and high mountain ranges.