A genetically modified organism (GMO) is any organism whose genetic material has been altered using genetic engineering techniques. The exact definition of a genetically modified organism and what constitutes genetic engineering varies, with the most common being an organism altered in a way that "does not occur naturally by mating and/or natural recombination". A wide variety of organisms have been genetically modified (GM), from animals to plants and microorganisms. Genes have been transferred within the same species, across species and even across kingdoms. New genes can be introduced, or endogenous genes can be enhanced, altered or knocked out.

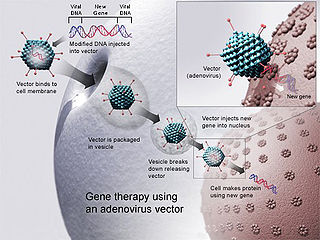

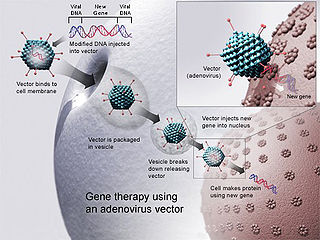

Gene therapy is a medical field which focuses on the utilization of the therapeutic delivery of nucleic acid into a patient's cells as a drug to treat disease. The first attempt at modifying human DNA was performed in 1980 by Martin Cline, but the first successful nuclear gene transfer in humans, approved by the National Institutes of Health, was performed in May 1989. The first therapeutic use of gene transfer as well as the first direct insertion of human DNA into the nuclear genome was performed by French Anderson in a trial starting in September 1990. It is thought to be able to cure many genetic disorders or treat them over time.

A designer baby is a baby whose genetic makeup has been selected or altered, often to include a particular gene or to remove genes associated with a disease. This process usually involves analysing a wide range of human embryos to identify genes associated with particular diseases and characteristics, and selecting embryos that have the desired genetic makeup; a process known as preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Other potential methods by which a baby's genetic information can be altered involve directly editing the genome – a person's genetic code – before birth. This process is not routinely performed and only one instance of this is known to have occurred as of 2019, where Chinese twins Lulu and Nana were edited as embryos, causing widespread criticism.

Genetically modified animals are animals that have been genetically modified for a variety of purposes including producing drugs, enhancing yields, increase resistance to disease, etc. The vast majority of genetically modified animals are at the research stage with the number close to entering the market remains small.

Michael W. Deem is the John W. Cox Professor of Biochemical and Genetic Engineering and Professor of Physics & Astronomy at Rice University in Houston, Texas. He is known for his work in parallel tempering and proposals to improve vaccine development by estimating the antigenic "distance" for any two samples of virus. His awards include a National Science Foundation CAREER Awards (1997), Top 100 Young Innovator, MIT Technology Review (1999) and Alfred P. Sloan Fellow (2000).

Genome editing, or genome engineering, or gene editing, is a type of genetic engineering in which DNA is inserted, deleted, modified or replaced in the genome of a living organism. Unlike early genetic engineering techniques that randomly inserts genetic material into a host genome, genome editing targets the insertions to site specific locations.

Genetic engineering can be accomplished using multiple techniques. There are a number of steps that are followed before a genetically modified organism (GMO) is created. Genetic engineers must first choose what gene they wish to insert, modify, or delete. The gene must then be isolated and incorporated, along with other genetic elements, into a suitable vector. This vector is then used to insert the gene into the host genome, creating a transgenic or edited organism. The ability to genetically engineer organisms is built on years of research and discovery on how genes function and how we can manipulate them. Important advances included the discovery of restriction enzymes and DNA ligases and the development of polymerase chain reaction and sequencing.

A gene drive is a genetic engineering technology that propagates a particular suite of genes throughout a population by altering the probability that a specific allele will be transmitted to offspring from the natural 50% probability. Gene drives can arise through a variety of mechanisms. They have been proposed to provide an effective means of genetically modifying specific populations and entire species.

Biotechnology risk is a form of existential risk that could come from biological sources, such as genetically engineered biological agents. These can come either intentionally or unintentionally. A chapter in biotechnology and biosecurity was published in Nick Bostrom's Global Catastrophic Risks, which covered risks such as viral agents. Since then, new technologies like CRISPR and gene drives have been introduced.

Josiah Zayner is a biohacker and scientist best known for his self-experimentation and his work making hands-on genetic engineering accessible to a lay audience, including CRISPR.

John Jin Zhang is a medical scientist who made important contributions in fertility research, and particularly in in vitro fertilization. He made headlines in September 2016 for successfully producing the world's first three-parent baby using the spindle transfer technique of mitochondrial replacement. Having obtained an M.D. from Zhejiang University School of Medicine, an M.Sc. from University of Birmingham, and a Ph.D. from University of Cambridge, he became the founder-director of New Hope Fertility Center in New York, USA.

Human germline engineering is the process by which the genome of an individual is edited in such a way that the change is heritable. This is achieved through genetic alterations within the germ cells, or the reproductive cells, such as the egg and sperm. Human Germline engineering is a type of genetic modification that directly manipulates the genome using molecular engineering techniques. Aside from germline engineering, genetic modification can be applied in another way, somatic genetic modification Somatic gene modification consists of altering somatic cells, which are all cells in the body that are not involved in reproduction. While somatic gene therapy does change the genome of the targeted cells, these cells are not within the germline, so the alterations are not heritable and cannot be passed on to the next generation.

Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua are a pair of identical crab-eating macaques that were created through somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), the same cloning technique that produced Dolly the sheep in 1996. They are the first cloned primates produced by this technique. Unlike previous attempts to clone monkeys, the donated nuclei came from fetal cells, not embryonic cells. The primates were both born at the Institute of Neuroscience of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai.

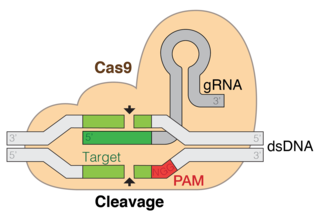

Off-target genome editing refers to nonspecific and unintended genetic modifications that can arise through the use of engineered nuclease technologies such as: clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALEN), meganucleases, and zinc finger nucleases (ZFN). These tools use different mechanisms to bind a predetermined sequence of DNA (“target”), which they cleave, creating a double-stranded chromosomal break (DSB) that summons the cell's DNA repair mechanisms and leads to site-specific modifications. If these complexes do not bind at the target, often a result of homologous sequences and/or mismatch tolerance, they will cleave off-target DSB and cause non-specific genetic modifications. Specifically, off-target effects consist of unintended point mutations, deletions, insertions inversions, and translocations.

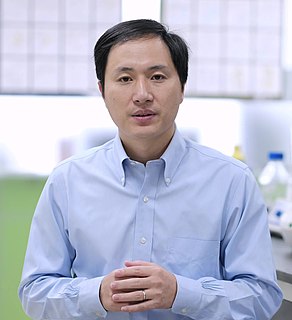

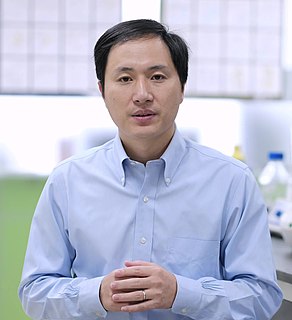

He Jiankui is a Chinese biophysics researcher who was an associate professor in the Department of Biology of the Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech) in Shenzhen, China. Earning his Ph.D. from Rice University in Texas on protein evolution including that of CRISPR, He Jiankui learned gene-editing technique (CRISPR/Cas9) as a postdoctoral researcher at Standford University in California.

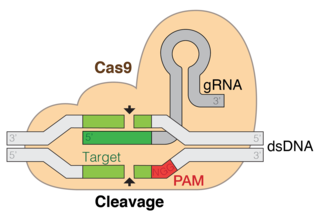

CRISPR gene editing is a method by which the genomes of living organisms may be edited. It is based on a simplified version of the bacterial CRISPR/Cas (CRISPR-Cas9) antiviral defense system. By delivering the Cas9 nuclease complexed with a synthetic guide RNA (gRNA) into a cell, the cell's genome can be cut at a desired location, allowing existing genes to be removed and/or new ones added.

Human Nature is a 2019 documentary film directed by Adam Bolt and written by Adam Bolt and Regina Sobel. Producers of the film include Greg Boustead, Elliot Kirschner and Dan Rather.

Chen Hu was a Chinese military physician and stem cell researcher. He served as Director of the PLA Institute of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Research and the Beijing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Therapy Laboratory. Known for his research on hematopoietic stem cell therapy for leukemia, he was awarded the State Science and Technology Progress Award in 2015 and the Ho Leung Ho Lee Prize in 2016. In 2017, he and Deng Hongkui engineered resistance to HIV in mice using CRISPR gene editing, and for the first time used the technique on an AIDS patient. He died of a sudden heart attack before their findings were published.

Deng Hongkui is a Chinese immunologist and stem cell researcher. He is a Changjiang Professor, the Boya Chair Professor, and Director of the Institute of Stem Cell Research at Peking University. He was awarded US$1.9 million by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for his research on vaccines for HIV and hepatitis C. In 2017, he and Chen Hu engineered resistance to HIV in mice using CRISPR gene editing, and for the first time used the technique on an AIDS patient.

Unnatural Selection is a 2019 TV documentary series that presents an overview of genetic engineering and particularly, the DNA-editing technology of CRISPR, from the perspective of scientists, corporations and biohackers working from their home. It was released by Netflix on October 18, 2019.