A creation myth is a symbolic narrative of how the world began and how people first came to inhabit it. While in popular usage the term myth often refers to false or fanciful stories, members of cultures often ascribe varying degrees of truth to their creation myths. In the society in which it is told, a creation myth is usually regarded as conveying profound truths – metaphorically, symbolically, historically, or literally. They are commonly, although not always, considered cosmogonical myths – that is, they describe the ordering of the cosmos from a state of chaos or amorphousness.

In Greek mythology, Tartarus is the deep abyss that is used as a dungeon of torment and suffering for the wicked and as the prison for the Titans. Tartarus is the place where, according to Plato's Gorgias, souls are judged after death and where the wicked received divine punishment. Tartarus is also considered to be a primordial force or deity alongside entities such as the Earth, Night, and Time.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Zagreus was sometimes identified with a god worshipped by the followers of Orphism, the "first Dionysus", a son of Zeus and Persephone, who was dismembered by the Titans and reborn. In the earliest mention of Zagreus, he is paired with Gaia and called the "highest" god, though perhaps only in reference to the gods of the underworld. Aeschylus, however, links Zagreus with Hades, possibly as Hades' son, or as Hades himself. Noting "Hades' identity as Zeus' katachthonios alter ego", Timothy Gantz postulated that Zagreus, originally the son of Hades and Persephone, later merged with the Orphic Dionysus, the son of Zeus and Persephone.

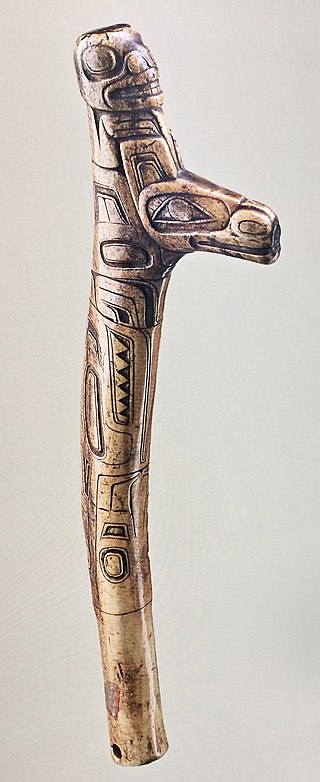

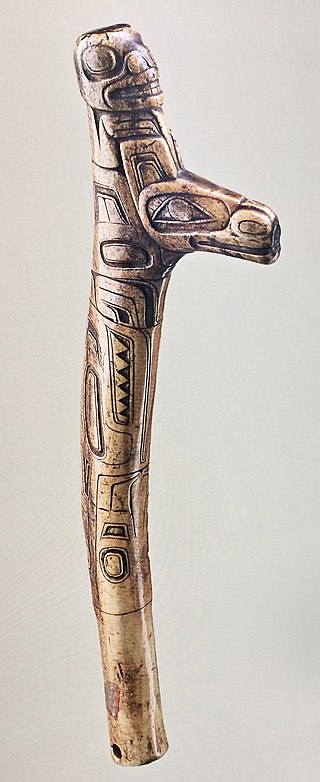

Tsimshian mythology is the mythology of the Tsimshian, an Aboriginal people in Canada and a Native American tribe in the United States. The majority of Tsimshian people live in British Columbia, while others live in Alaska.

The Tumbuka are an ethnic group living in Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. In Tumbuka mythology, Chiuta is the Supreme Creator and is symbolised in the sky by the rainbow.

A culture hero is a mythological hero specific to some group who changes the world through invention or discovery. Although many culture heroes help with the creation of the world, most culture heroes are important because of their effect on the world after creation. A typical culture hero might be credited as the discoverer of fire, agriculture, songs, tradition, law, or religion, and is usually the most important legendary figure of a people, sometimes as the founder of its ruling dynasty.

Afrocentrism is an approach to the study of world history that focuses on the history of people of recent African descent. It is in some respects a response to Eurocentric attitudes about African people and their historical contributions. It seeks to counter what it sees as mistakes and ideas perpetuated by the racist philosophical underpinnings of Western academic disciplines as they developed during and since Europe's Early Renaissance as justifying rationales for the enslavement of other peoples, in order to enable more accurate accounts of not only African but all people's contributions to world history. Afrocentricity deals primarily with self-determination and African agency and is a Pan-African point of view for the study of culture, philosophy, and history.

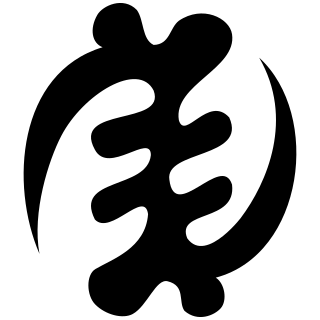

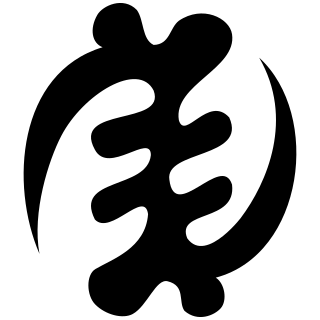

Onyame, Nyankopon (Onyankapon) and Odomankoma are the trinity of the supreme god of the Akan people of Ghana, who is most commonly known as Nyame. His name means "He who knows and sees everything", and "omniscient, omnipotent sky deity" in the Akan language.

Coyote is a mythological character common to many cultures of the Indigenous peoples of North America, based on the coyote animal. This character is usually male and is generally anthropomorphic, although he may have some coyote-like physical features such as fur, pointed ears, yellow eyes, a tail and blunt claws. The myths and legends which include Coyote vary widely from culture to culture.

The mythology of the Miwok Native Americans are myths of their world order, their creation stories and 'how things came to be' created. Miwok myths suggest their spiritual and philosophical world view. In several different creation stories collected from Miwok people, Coyote was seen as their ancestor and creator god, sometimes with the help of other animals, forming the earth and making people out of humble materials like feathers or twigs.

Many references to ravens exist in world lore and literature. Most depictions allude to the appearance and behavior of the wide-ranging common raven. Because of its black plumage, croaking call, and diet of carrion, the raven is often associated with loss and ill omen. Yet, its symbolism is complex. As a talking bird, the raven also represents prophecy and insight. Ravens in stories often act as psychopomps, connecting the material world with the world of spirits.

Death is frequently imagined as a personified force. In some mythologies, a character known as the Grim Reaper causes the victim's death by coming to collect that person's soul. Other beliefs hold that the Spectre of Death is only a psychopomp, a benevolent figure who serves to gently sever the last ties between the soul and the body, and to guide the deceased to the afterlife, without having any control over when or how the victim dies. Death is most often personified in male form, although in certain cultures Death is perceived as female . Death is also portrayed as one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

In mythology and the study of folklore and religion, a trickster is a character in a story who exhibits a great degree of intellect or secret knowledge and uses it to play tricks or otherwise disobey normal rules and defy conventional behavior.

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of deities, heroes, and mythological creatures, and the origins and significance of the ancient Greeks' own cult and ritual practices. Modern scholars study the myths to shed light on the religious and political institutions of ancient Greece, and to better understand the nature of myth-making itself.

Bantu mythology is the system of beliefs and legends of the Bantu people of Africa. Although Bantu peoples account for several hundred different ethnic groups, there is a high degree of homogeneity in Bantu cultures and customs, just as in Bantu languages.

Marimba Ani is an anthropologist and African Studies scholar best known for her work Yurugu, a comprehensive critique of European thought and culture, and her coining of the term "Maafa" for the African holocaust.

The theft of fire for the benefit of humanity is a theme that recurs in many world mythologies. This narrative is classified in the Motif-Index of Folk-Literature as motif A1415. Its recurrent themes include a trickster figure as the thief, and a supernatural guardian who hoards fire from humanity, often out of mistrust for humans.

Tano (Tanoɛ), whose true name is Ta Kora, but is often confused with Tano Akora, and is known as Tando to the Fante is the Abosom of war and strife in Akan mythology and Abosom of Thunder and Lightning in the Asante mythology of Ghana as well as the Agni mythology of the Ivory Coast. He represents the Tano River, which is located in Ghana. He is regarded as the highest atano, or Tano abosom in Akan mythology.

Owuo is the abosom of Death in the Asante and Akan mythology of West Ghana and the Krachi peoples of East Ghana and Togo. He is represented with the Adinkra symbol of a ladder. It is said that he was created by Odomankoma just so he could kill humans and possibly other deities, such as Odomankoma himself. He signifies the termination of the creative process in the world, a reference to him killing Odomankoma, the Great Creator