The Hutu, also known as the Abahutu, are a Bantu ethnic or social group which is native to the African Great Lakes region. They mainly live in Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda where they form one of the principal ethnic groups alongside the Tutsi and the Great Lakes Twa.

The Tutsi, also called Watusi, Watutsi or Abatutsi, are an ethnic group of the African Great Lakes region. They are a Bantu-speaking ethnic group and the second largest of three main ethnic groups in Rwanda and Burundi.

The Nilotic peoples are people indigenous to the Nile Valley who speak Nilotic languages. They inhabit South Sudan, Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, the eastern border area of Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. Among these are the Burun-speaking peoples, Teso people also known as Iteso or people of Teso, Karo peoples, Luo peoples, Ateker peoples, Kalenjin peoples, Karamojong people also known as the Karamojong or Karimojong, Datooga, Dinka, Nuer, Atwot, Lotuko, and the Maa-speaking peoples.

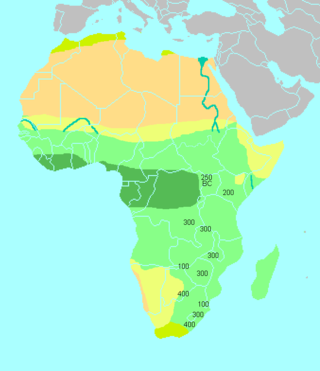

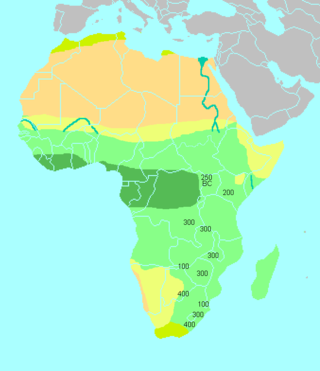

The Bantu expansion was a major series of migrations of the original Proto-Bantu-speaking group, which spread from an original nucleus around West-Central Africa. In the process, the Proto-Bantu-speaking settlers displaced, eliminated or absorbed pre-existing hunter-gatherer and pastoralist groups that they encountered.

Banyamulenge is a community from the Democratic Republic of the Congo's South Kivu province. The Banyamulenge are culturally and socially distinct from the Tutsi of South Kivu, with most speaking Kinyamulenge, a mix of Kinyarwanda, Kirundi, Ha language, and Swahili. Banyamulenge are often discriminated against in the DRC due to their Tutsi phenotype, similar to that of people living in the Horn of Africa, their insubordination towards colonial rule, their role in Mobutu's war against and victory over the Simba Rebellion, which was supported by the majority of other tribes in South Kivu, their role during the First Congo War and subsequent regional conflicts (Rally for Congolese Democracy–Goma, Movement for the Liberation of the Congo, National Congress for the Defence of the People, and more importantly for the fact that two of the most influential presidents of their country declared them as enemy of the State both in 1996 and 1998.

Lactase persistence or lactose tolerance is the continued activity of the lactase enzyme in adulthood, allowing the digestion of lactose in milk. In most mammals, the activity of the enzyme is dramatically reduced after weaning. In some human populations though, lactase persistence has recently evolved as an adaptation to the consumption of nonhuman milk and dairy products beyond infancy. Lactase persistence is very high among northern Europeans, especially Irish people. Worldwide, most people are lactase non-persistent, and are affected by varying degrees of lactose intolerance as adults. However, lactase persistence and lactose intolerance can overlap.

The Rendille are a Cushitic ethnic group inhabiting the Eastern Province of Kenya.

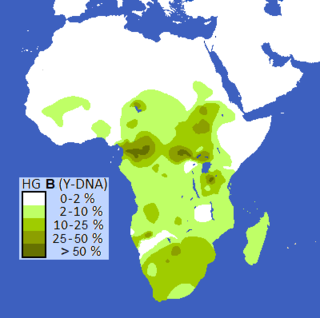

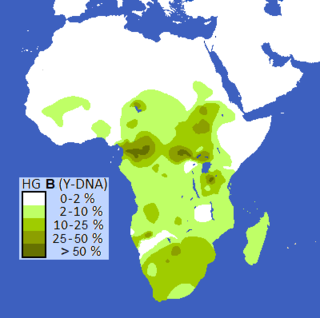

Haplogroup B (M60) is a human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup common to paternal lineages in Africa. It is a primary branch of the haplogroup BT.

The Iraqw People are a Cushitic ethnic group inhabiting the northern Tanzanian regions. They dwells in southwestern Arusha and Manyara regions of Tanzania, near the Rift Valley. The Iraqw people then settled in the southeast of Ngorongoro Crater in northern Karatu District, Arusha Region, where the majority of them still reside. In the Manyara region, the Iraqw are a major ethnic group, specifically in Mbulu District, Babati District and Hanang District.

The Banyarwanda are a Bantu ethnolinguistic supraethnicity. The Banyarwanda are also minorities in neighboring Burundi, DR Congo, Uganda, Tanzania.

Hutu Power is a ethnic supremacist ideology that asserts the ethnic superiority of Hutu, often in the context of being superior to Tutsi and Twa, and that therefore they are entitled to dominate and murder these two groups and other minorities. Espoused by Hutu extremists, widespread support for the ideology led to the 1994 Rwandan genocide against Tutsi and their family members, the moderate Hutu who opposed the killings, and Twa who were deemed traitors. Hutu Power political parties and movements included the Akazu, the Coalition for the Defence of the Republic and its Impuzamugambi paramilitary militia, and the governing National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development and its Interahamwe paramilitary militia. The theory of Hutu people being superior is most common in Rwanda and Burundi, where they make up the majority of the population. Due to its sheer destructiveness, the ideology has been compared to historical Nazism in the Western world.

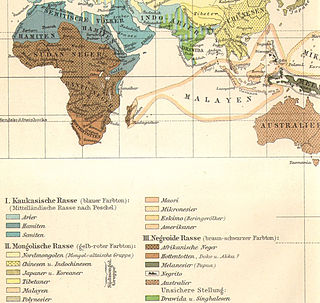

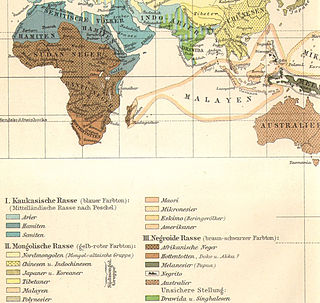

Hamites is the name formerly used for some Northern and Horn of Africa peoples in the context of a now-outdated model of dividing humanity into different races; this was developed originally by Europeans in support of colonialism and slavery. The term was originally borrowed from the Book of Genesis, in which it refers to the descendants of Ham, son of Noah.

Haplogroup E-M75 is a human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. Along with haplogroup E-P147, it is one of the two main branches of the older haplogroup E-M96.

Ethnic groups in Burundi include the three main indigenous groups of Hutu, Tutsi and Twa that have largely been emphasized in the study of the country's history due to their role in shaping it through conflict and consolidation. Burundi's ethnic make-up is similar to that of neighboring Rwanda. Additionally, recent immigration has also contributed to Burundi's ethnic diversity. Throughout the country's history, the relation between the ethnic groups has varied, largely depending on internal political, economic and social factors and also external factors such as colonialism. The pre-colonial era, despite having divisions between the three groups, saw greater ethnic cohesion and fluidity dependent on socioeconomic factors. During the colonial period under German and then Belgian rule, ethnic groups in Burundi experienced greater stratifications and solidification through biological arguments separating the groups and indirect colonial rule that increased group tensions. The post-independence Burundi has experienced recurring inter-ethnic violence especially in the political arena that has, in turn, spilled over to society at large leading to many casualties throughout the decades. The Arusha Agreement served to end the decades-long ethnic tensions, and the Burundian government has stated commitment to creating ethnic cohesion in the country since, yet recent waves of violence and controversies under the Pierre Nkurunziza leadership have worried some experts of potential resurfacing of ethnic violence. Given the changing nature of ethnicity and ethnic relations in the country, many scholars have approached the topic theoretically to come up with primordial, constructivist and mixed arguments or explanations on ethnicity in Burundi.

The largest ethnic groups in Rwanda are the Hutus, which make up about 85% of Rwanda's population; the Tutsis, which are 14%; and the Twa, which are around 1%. Starting with the Tutsi feudal monarchy rule of the 10th century, the Hutus were a subjugated social group. Belgian colonization also contributed to the tensions between the Hutus and Tutsis. The Belgians and later the Hutus propagated the myth that Hutus were the superior ethnicity. The resulting tensions would eventually foster the slaughtering of Tutsis in the Rwandan genocide. Since then, policy has changed to recognize one main ethnicity: "Rwandan".

The Rwandan Revolution, also known as the Hutu Revolution, Social Revolution, or Wind of Destruction, was a period of ethnic violence in Rwanda from 1959 to 1961 between the Hutu and the Tutsi, two of the three ethnic groups in Rwanda. The revolution saw the country transition from a Tutsi monarchy under Belgian colonial authority to an independent Hutu-dominated republic.

The African Pygmies are a group of ethnicities native to Central Africa, mostly the Congo Basin, traditionally subsisting on a forager and hunter-gatherer lifestyle. They are divided into three roughly geographic groups:

Sarah Anne Tishkoff is an American geneticist and the David and Lyn Silfen Professor in the Department of Genetics and Biology at the University of Pennsylvania. She also serves as a director for the American Society of Human Genetics and is an associate editor at PLOS Genetics, G3, and Genome Research. She is also a member of the scientific advisory board at the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

The genetic history of Africa summarizes the genetic makeup and population history of African populations in Africa, composed of the overall genetic history, including the regional genetic histories of North Africa, West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa, as well as the recent origin of modern humans in Africa. The Sahara served as a trans-regional passageway and place of dwelling for people in Africa during various humid phases and periods throughout the history of Africa.

Rwanda's prehistory is a relatively unexplored concept as compared to other regions of Africa. Most archaeological works regarding Rwanda past 1994 are associated with conflict and ethnic violence. However more recently, archaeologists have been attempting to focus on archaeological works from the first and second millennia A.D. For example, some archaeological research has been focusing on the Nyiginya Kingdom, which is the pre-colonial predecessor of the current Rwandan state. Other research has been focusing on the excavations of the earliest agricultural sites, likely from the Iron Age, as well as ceramics to indicate chronology of when certain agricultural groups migrated to Rwanda.