Pharmaceutical policy is a branch of health policy that deals with the development, provision and use of medications within a health care system. It embraces drugs (both brand name and generic), biologics (products derived from living sources, as opposed to chemical compositions), vaccines and natural health products.

In many countries, an agency of the national government (in the U.S. the NIH, in the U.K. the MRC, and in India the DST) funds university researchers to study the causes of disease, which in some cases leads to the development of discoveries which can be transferred to pharmaceutical companies and biotechnology companies as a basis for drug development. By setting its budget, its research priorities and making decisions about which researchers to fund, there can be a significant impact on the rate of new drug development and on the disease areas in which new drugs are developed. For example, a major investment by the NIH into research on HIV in the 1980s certainly could be viewed as an important foundation for the many antiviral drugs that have subsequently been developed. [1]

While patent laws are written to apply to all inventions, whether mechanical, pharmaceutical, or electronic, the interpretations of patent law made by government patent granting agencies (the United States Patent and Trademark Office, for example) and courts, can be very subject-matter specific with significant impact on the incentives for drug development and the availability of lower-priced generic drugs. For example, a recent decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Pfizer v. Apotex, 480 F.3d 1348 (Fed.Cir.2007), held invalid a patent on the "pharmaceutical salt" formulation of a previously patented active ingredient. If that decision is not overturned by the United States Supreme Court, generic versions of the drug in controversy, Norvasc (amlodipine besylate) will be available much earlier. If the reasoning of the Federal Circuit in the case is applied more generally to other patents on pharmaceutical formulations, it would have a significant impact in speeding generic drug availability (and, conversely, some negative impact on the incentives and funding for the research and development of new drugs). [2]

This involves the approval of a product for sale in a jurisdiction. Typically a national agency such as the US Food and Drug Administration (specifically, the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, or CDER), the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency or Health Canada or Ukrainian Drug Registration Agency [3] is responsible for reviewing a product and approving it for sale. The regulatory process typically focuses on quality, safety and efficacy. To be approved for sale a product must demonstrate that it is generally safe (or has a favourable risk/benefit profile relative to the condition it is intended to treat), that it does what the manufacturer claims and that it is produced to high standards. Internal staff and expert advisory committees review products. Once approved, a product is given an approval letter or issued with a notice of compliance, indicating that it may now be sold in the jurisdiction. In some cases, such approvals may have conditions attached, requiring, for example additional 'post-marketing' trials to clarify an issue (such as efficacy in certain patient populations or interactions with other products) or criteria limiting the product to certain uses.

In many jurisdictions drug prices are regulated. For example, in the UK the Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme is intended to ensure that the National Health Service is able to purchase drugs at "reasonable prices". In Canada, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board examines drug pricing, compares the proposed Canadian price to that of seven other countries and determines if a price is "excessive" or not. In these circumstances, drug manufacturers must submit a proposed price to the appropriate regulatory agency. [4]

Once a regulatory agency has determined the clinical benefit and safety of a product and pricing has been confirmed (if necessary), a drug manufacturer will typically submit it for evaluation by a payer of some sort. Payers may be private insurance plans, governments (through the provision of benefits plans to insured populations or specialized entities like Cancer Care Ontario, which funds in-hospital oncology drugs) or health care organizations such as hospitals. At this point the critical issue is cost-effectiveness. This is where the discipline of pharmaco-economics is often applied. This is a specialized field of health economics that looks at the cost/benefit of a product in terms of quality of life, alternative treatments (drug and non-drug) and cost reduction or avoidance in other parts of the health care system (for example, a drug may reduce the need for a surgical intervention, thereby saving money). Structures like the UK's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and Canada's Common Drug Review evaluate products in this way. Some jurisdictions do not, however, evaluate products for cost-effectiveness. In some instances, individual drug benefit plans (or their administrators) may also evaluate products. Additionally, hospitals may have their own review committees (often called a Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee) to make decisions about which drugs to fund from the hospital budget.

Drug plan administrators may also apply their own pricing rules outside of that set by national pricing agencies. For example, British Columbia uses a pricing model called reference-based pricing to set the price of drugs in certain classes. Many US pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) use strategies like tiered formularies and preferred listings to encourage competition and downward pricing pressure, resulting in lower prices for benefits plans. Competitive procurement of this sort is common among large purchasers such as the US Veteran's Health Administration.

Typically, a manufacturer will provide an estimate of the projected use of a drug as well as the expected fiscal impact on a drug plan's budget. If necessary, a drug plan may negotiate a risk-sharing agreement to mitigate the potential for an unexpectedly large budget impact due to incorrect assumptions and projections.

Because the clinical trials used to generate information to support drug licensing are limited in scope and duration, drug plans may request ongoing post-market trials (often called Phase IV or pragmatic clinical trials) to demonstrate a product's 'real world safety and effectiveness.' These may take the form of a patient registry or other means of data collection and analysis.

Once a product is deemed cost-effective, a price negotiated (or applied in the case of a pricing model) and any risk-sharing agreement negotiated, the drug is placed on a drug list or formulary. Prescribers may choose drugs on the list for their patients, subject to any conditions or patient criteria. [5]

At the core of most reimbursement regimes is the drug list, or formulary. Managing this list can involve many different approaches. Negative lists – products that are not reimbursed under any circumstances are used in some jurisdictions (c.f. Germany). More dynamic formularies may have graduated listings such as Ontario's recent conditional listing model. As mentioned, formularies may be used to drive choice to lower cost drugs by structuring a sliding scale of co-payments favouring cheaper products or those for which there is a preferential agreement with the manufacturer. This is the principle underlying preferred drug lists used in many US state Medicaid programs. Some jurisdictions and plans (such as Italy) may also categorize drugs according to their 'essentialness' and determine the level of reimbursement the plan will provide and the portion that the patient is expected to pay.

Formularies may also segment drugs into categories for which a prior authorization is needed. This is usually done to limit the use of a high cost drug or one that has potential for inappropriate use (sometimes called 'off-label' as it involves using a product to treat conditions other than those for which its license was granted). In this circumstance a health care provider would have to seek permission to prescribe the product or the pharmacist would have to obtain permission prior to dispensing it. [6]

Depending on the structure of the health care system, drugs may be purchased by patients themselves, a health care organization on behalf of patients or an insurance plan (public or private). Hospitals typically limit eligibility to their in-patients. Private plans may be employer-sponsored such as Blue Cross, mandated by legislation, as in Quebec or consist of an outsourcing arrangement for a public plan, such as the US Medicare Part D scheme. Public plans may be structured in a variety of ways including:

Additionally, plans may be structured to respond to the 'catastrophic' impact of drug expenses incurred by those with serious diseases or high drug spending relative to income. These patient populations, often called 'medically needy,' may have all or part of their drug costs covered by 'plans of last resort,' (typically government-sponsored). One such plan is Ontario's Trillium Drug Program.

Pharmaceutical policy may also be used to respond to health crises. For example, Argentina launched REMEDIAR during its financial crisis of 2002. The government-sponsored program provides a specified list of essential drugs to primary care clinics in low-income neighbourhoods. Similarly, Brazil provides drugs for HIV/AIDS free to all citizens as a deliberate public health policy choice.

Eligibility policy also focuses on cost-sharing between a plan and the beneficiary (the insured person). Co-payments may be used to drive certain prescribing choices (for example, favouring generic over brand drugs or preferred over non-preferred products). Deductibles may be used as part of geared to income plans. [7]

Pharmaceutical policy may also attempt to shape and inform prescribing. Prescribing may be limited to physicians or include certain classes of health care providers such as nurse practitioners and pharmacists. There may be limitations placed on each class of provider. This may take the form of prescribing criteria for a drug, limiting its prescribing to a particular type of specialist physician for example (such as HIV/AIDS drugs to physicians with advanced training in this area), or it may involve special drug lists that a specific type of health care provider (such as a nurse practitioner) may prescribe from. [8]

Plans may also seek to influence prescribing by providing information to prescribers. This practice is often called 'academic detailing' to differentiate it from the detailing (provision of drug information) done by pharmaceutical companies. Organizations such as Australia's National Prescribing Service typify this technique, providing independent information, including head-to-head comparisons and cost-effectiveness information to prescribers to influence their choices. [9]

Additionally, efforts to promote the 'appropriate use' of medications may also involve other providers like pharmacists providing clinical consulting services. In settings such as hospitals and long-term care, pharmacists often collaborate closely with physicians to ensure optimal prescribing choices are made. In some jurisdictions, such as Australia, pharmacists are compensated for providing medication reviews for patients outside of acute or long-term care settings. Pharmacist collaboration with family physicians in order to improve prescribing may also be funded. [10]

Pharmaceutical policy may also encompass how drugs are provided to beneficiaries. This includes the mechanics of drug distribution and dispensing as well as the funding of such services. For example, some HMOs in the US use a 'central fill' approach where all prescriptions are packaged and shipped from a central location instead of at a community pharmacy. In other jurisdictions, retail pharmacies are compensated for dispensing drugs to eligible beneficiaries. A state-operated approach may also be taken, as with Sweden's Apoteket, which had the monopoly on retail pharmacy until 2009, and was not-for-profit. Pharmaceutical policy may also subsidize smaller, more marginal pharmacies, using the rationale that they are needed health care providers. The UK's Essential Small Pharmacies Scheme works this way. [11]

The British National Formulary (BNF) is a United Kingdom (UK) pharmaceutical reference book that contains a wide spectrum of information and advice on prescribing and pharmacology, along with specific facts and details about many medicines available on the UK National Health Service (NHS). Information within the BNF includes indication(s), contraindications, side effects, doses, legal classification, names and prices of available proprietary and generic formulations, and any other notable points. Though it is a national formulary, it nevertheless also includes entries for some medicines which are not available under the NHS, and must be prescribed and/or purchased privately. A symbol clearly denotes such drugs in their entry.

A pharmacist is a healthcare professional who specializes in the preparation, dispensing, and management of medications and who provides pharmaceutical advice and guidance. Pharmacists often serve as primary care providers in the community, and may offer other services such as health screenings and immunizations.

Pharmacy is the science and practice of discovering, producing, preparing, dispensing, reviewing and monitoring medications, aiming to ensure the safe, effective, and affordable use of medicines. It is a miscellaneous science as it links health sciences with pharmaceutical sciences and natural sciences. The professional practice is becoming more clinically oriented as most of the drugs are now manufactured by pharmaceutical industries. Based on the setting, pharmacy practice is either classified as community or institutional pharmacy. Providing direct patient care in the community of institutional pharmacies is considered clinical pharmacy.

A prescription, often abbreviated ℞ or Rx, is a formal communication from a physician or other registered healthcare professional to a pharmacist, authorizing them to dispense a specific prescription drug for a specific patient. Historically, it was a physician's instruction to an apothecary listing the materials to be compounded into a treatment—the symbol ℞ comes from the first word of a medieval prescription, Latin recipere, that gave the list of the materials to be compounded.

Prescription drug list prices in the United States continually are among the highest in the world. The high cost of prescription drugs became a major topic of discussion in the 21st century, leading up to the American health care reform debate of 2009, and received renewed attention in 2015. One major reason for high prescription drug prices in the United States relative to other countries is the inability of government-granted monopolies in the American health care sector to use their bargaining power to negotiate lower prices, and the American payer ends up subsidizing the world's R&D spending on drugs.

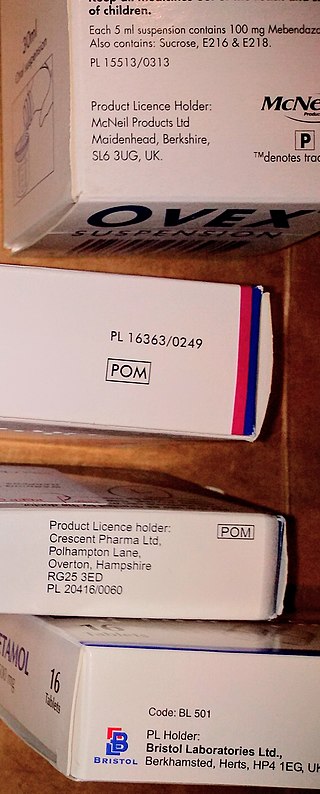

A prescription drug is a pharmaceutical drug that is permitted to be dispensed only to those with a medical prescription. In contrast, over-the-counter drugs can be obtained without a prescription. The reason for this difference in substance control is the potential scope of misuse, from drug abuse to practicing medicine without a license and without sufficient education. Different jurisdictions have different definitions of what constitutes a prescription drug.

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) is a program of the Australian Government that subsidises prescription medication for Australian citizens and permanent residents, as well as international visitors covered by a reciprocal health care agreement. The PBS is separate to the Medicare Benefits Schedule, a list of health care services that can be claimed under Medicare, Australia's universal health care insurance scheme.

Official website

An essential medicines policy is one that aims at ensuring that people get good quality drugs at the lowest possible price, and that doctors prescribe the minimum of required drugs in order to treat the patient's illness. The pioneers in this field were Sri Lanka and Chile.

Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) is a committee at a hospital or a health insurance plan that decides which drugs will appear on that entity's drug formulary. The committee usually consists of healthcare providers involved in prescribing, dispensing, and administering medications, as well as administrators who evaluate medication use. They must weigh the costs and benefits of each drug and decide which ones provide the most efficacy per dollar. This is one aspect of pharmaceutical policy. P&T committees utilize an evidence-based approach to drive change within health systems/plans by changing existing policies and bringing up-to-date research to support medical decision-making.

In the United States, a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) is a third-party administrator of prescription drug programs for commercial health plans, self-insured employer plans, Medicare Part D plans, the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program, and state government employee plans. According to the American Pharmacists Association, "PBMs are primarily responsible for developing and maintaining the formulary, contracting with pharmacies, negotiating discounts and rebates with drug manufacturers, and processing and paying prescription drug claims." PBMs operate inside of integrated healthcare systems, as part of retail pharmacies, and as part of insurance companies.

Many developing nations have developed national drug policies, a concept that has been actively promoted by the WHO. For example, the national drug policy for Indonesia drawn up in 1983 had the following objectives:

Clinical pharmacy is the branch of pharmacy in which clinical pharmacists provide direct patient care that optimizes the use of medication and promotes health, wellness, and disease prevention. Clinical pharmacists care for patients in all health care settings but the clinical pharmacy movement initially began inside hospitals and clinics. Clinical pharmacists often work in collaboration with physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other healthcare professionals. Clinical pharmacists can enter into a formal collaborative practice agreement with another healthcare provider, generally one or more physicians, that allows pharmacists to prescribe medications and order laboratory tests.

A pharmacy is a retail shop which provides pharmaceutical drugs, among other products. At the pharmacy, a pharmacist oversees the fulfillment of medical prescriptions and is available to counsel patients about prescription and over-the-counter drugs or about health problems and wellness issues. A typical pharmacy would be in the commercial area of a community.

Medication costs, also known as drug costs are a common health care cost for many people and health care systems. Prescription costs are the costs to the end consumer. Medication costs are influenced by multiple factors such as patents, stakeholder influence, and marketing expenses. A number of countries including Canada, parts of Europe, and Brazil use external reference pricing as a means to compare drug prices and to determine a base price for a particular medication. Other countries use pharmacoeconomics, which looks at the cost/benefit of a product in terms of quality of life, alternative treatments, and cost reduction or avoidance in other parts of the health care system. Structures like the UK's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and to a lesser extent Canada's Common Drug Review evaluate products in this way.

A formulary is a list of pharmaceutical drugs, often decided upon by a group of people, for various reasons such as insurance coverage or use at a medical facility. Traditionally, a formulary contained a collection of formulas for the compounding and testing of medication. Today, the main function of a prescription formulary is to specify particular medications that are approved to be prescribed at a particular hospital, in a particular health system, or under a particular health insurance policy. The development of prescription formularies is based on evaluations of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of drugs.

Electronic prescription is the computer-based electronic generation, transmission, and filling of a medical prescription, taking the place of paper and faxed prescriptions. E-prescribing allows a physician, physician assistant, pharmacist, or nurse practitioner to use digital prescription software to electronically transmit a new prescription or renewal authorization to a community or mail-order pharmacy. It outlines the ability to send error-free, accurate, and understandable prescriptions electronically from the healthcare provider to the pharmacy. E-prescribing is meant to reduce the risks associated with traditional prescription script writing. It is also one of the major reasons for the push for electronic medical records. By sharing medical prescription information, e-prescribing seeks to connect the patient's team of healthcare providers to facilitate knowledgeable decision making.

Specialty drugs or specialty pharmaceuticals are a recent designation of pharmaceuticals classified as high-cost, high complexity and/or high touch. Specialty drugs are often biologics—"drugs derived from living cells" that are injectable or infused. They are used to treat complex or rare chronic conditions such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, hemophilia, H.I.V. psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease and hepatitis C. In 1990 there were 10 specialty drugs on the market, around five years later nearly 30, by 2008 200, and by 2015 300.

Specialty pharmacy refers to distribution channels designed to handle specialty drugs — pharmaceutical therapies that are either high cost, high complexity and/or high touch. High touch refers to higher degree of complexity in terms of distribution, administration, or patient management which drives up the cost of the drugs. In the early years specialty pharmacy providers attached "high-touch services to their overall price tags" arguing that patients who receive specialty pharmaceuticals "need high levels of ancillary and follow-up care to ensure that the drug spend is not wasted on them." An example of a specialty drug that would only be available through specialty pharmacy is interferon beta-1a (Avonex), a treatment for MS that requires a refrigerated chain of distribution and costs $17,000 a year. Some specialty pharmacies deal in pharmaceuticals that treat complex or rare chronic conditions such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, hemophilia, H.I.V. psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or Hepatitis C. "Specialty pharmacies are seen as a reliable distribution channel for expensive drugs, offering patients convenience and lower costs while maximizing insurance reimbursements from those companies that cover the drug. Patients typically pay the same co-payments whether or not their insurers cover the drug." As the market demanded specialization in drug distribution and clinical management of complex therapies, specialized pharma (SP) evolved.„ Specialty pharmacies may handle therapies that are biologics, and are injectable or infused. By 2008 the pharmacy benefit management dominated the specialty pharmacies market having acquired smaller specialty pharmacies. PBMs administer specialty pharmacies in their network and can "negotiate better prices and frequently offer a complete menu of specialty pharmaceuticals and related services to serve as an attractive 'one-stop shop' for health plans and employers."

Separation of prescribing and dispensing, also called dispensing separation, is a practice in medicine and pharmacy in which the physician who provides a medical prescription is independent from the pharmacist who provides the prescription drug.