Piece-rate lists were the ways of assessing a cotton operatives pay in Lancashire in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They started as informal agreements made by one cotton master and their operatives then each cotton town developed their own list. Spinners merged all of these into two main lists which were used by all, while weavers used one 'unified' list. [1]

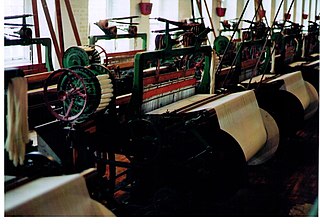

Early cotton spinning mills in Derbyshire and later in Manchester and Lancashire used cotton-jennies and mules. The proprietors put out the spun cotton to hand loom weavers who wove it into pieces for which they were paid. In the Pennine counties many established woollen weavers switched their looms to cotton and more entrepreneurs invested in cotton spinning mills. [2]

When cast iron power looms became reliable, the mill-owners added weaving sheds to their mills then employed relatively unskilled women and children (half-timers). Each minded four looms while a skilled tackler gaited the looms and kept them tuned. Mule-spinners and power loom weavers were also being paid by piece.

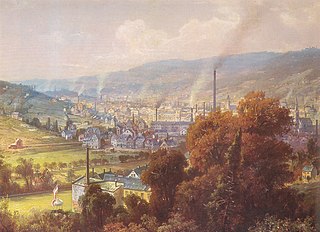

As the 18th century progressed each town developed a different specialism. Oldham was a spinning town producing fine counts while Wigan did coarse. Burnley became a weaving town, producing plain calicos for printing, while but Blackburn did fancies using Jacquard looms. In the 20th century there was consolidation into larger units of production. To the north-east thousand-loom sheds were built while to the south we saw the quarter of a million spindles Edwardian ring spinning mills. [3] Ring spinners were usually paid by the hour not the piece.

For the calculation of wages piece-rate lists were universally employed as regards the payment of full weavers and mule-spinners; some piecers got a definite share of the total wage thus assigned to a pair of mules, while others were paid a fixed weekly amount. Many ring-spinners were mainly paid an hourly wage. Other operatives were almost universally so paid by list, with the exception of the hands in the blowing-room and on the carding-machines. [4]

Individually negotiating with the spinner or weaver how much should be paid for each job clearly was not feasible and a table listing the payment for each task was drawn up by each employer. As operatives then moved to the proprietor who paid the most, 'lists' were put together to agree a standard between mills and sheds in a neighbourhood. The list ensured uniformity of treatment and became an item that demanded vigorous discussion to ensure the differentials were maintained. [3]

Spinning and weaving lists were most complicated; discounts were made in them for most incidents beyond the operatives' control. They could not cover all circumstances however, so much was left as to the manner of their application to private arrangement. [4]

The highest wages were earned by mule-spinners (who were all males); their assistants, known as piecers, were more poorly paid. Piecers would hope to eventually become "minders", i.e. mule-spinners in charge of mules. The division of the total wage paid on a pair of mules between the minder and the piecers was largely the result of the policy of the spinners' trade union. Almost without exception in Lancashire one minder took charge of a pair of mules with two or three piecers assisting. The wage of fine spinners about 25 to 35 above that of a coarse weaver. [5]

Among the weavers there was no rule as to the number of assistants to full weavers (who are both male and female), or, after the 'More looms system' came in, as to the number of looms managed by a weaver, but the proportion of assistants was less than in spinning branches. [5]

Discounts is the principle that no operative should suffer if he was allocated substandard cotton, or put on a machine that output a lower capacity. [6]

The history of lists stretches back to the first quarter of the 19th century as regards spinners, and to about the middle of the century generally as regards weavers, though a weaving list agreed to by eleven masters was drawn up as early as 1834. There are still many different district lists in use, but the favourite spinning lists are those of Oldham and Bolton, [7] and the weaving list most generally employed is that known as the "Uniform List" (1892), [8] which is a compromise between the lists of Blackburn, Preston and Burnley. [4]

A copy of the Bolton list of 1844 was published by the British Association Report in 1887, but this was not the first. [6] It is believed that the Bolton List for spinners dated from 1813 and this embraced discounts. It the 1830s there was much agitation to agree lists, and the Bolton list was often discussed. There was an Oldham List for weavers in 1834, this was in place fifteen years before the Oldham Weavers' Association was formed in 1859. The Burnley weaving list was drawn up in 1843 and the Blackburn lists for weaving, looming, winding, beam-warping and tape-sizing were drawn up by joint committees in 1853. [9]

In general, the pressure to adopt lists came from the operatives themselves. [lower-alpha 1] Many lists were drawn up and frequently revised, so by 1887, twenty two lists had been drawn up and most abandoned. [8] The Hyde, Stockport and Ashton lists were superseded by the Blackburn list (1853) for fine cloth- as had the Burnley, Chorley and Preston lists. When the Unified List was adopted in 1892, Ashton opted to stay with the Blackburn list. [10]

The lists attempted to achieve fairness, and as such were very complex and the emerging unions employed staff to check the calculations which were known as 'The Sorts'. [lower-alpha 2] David Shackleton, the future Independent Labour Party leader and MP for Clitheroe was employed by the Darwen Weavers', Winders' and Warpers' Association as secretary in 1894 . In two years, he recalculated 3,237 sorts and discovered 1290 underpayments. (40%) Some of these were honest mistakes other were due to the practice of 'nibbling'. [12] To put this in context Shackleton himself had attended a dame school and church primary schools for which his father was charged. He started work as a part-timer at the legal age of nine and full-time at 13. Though he attended night school classes he never progressed beyond a primary school level education. [13]

Lists continued until the 1920s

Under the "Particulars Clause", first included in a Factory Act 1891 and given extended application in 1895, the particulars required for the calculation of wages must be rendered by the employer. In spinning there used to be doubts about the quantity of work done, so the "indicator", which measures the length of yarn spun came into general use. The Oldham Spinning list differs from all others in that its basis is starts from an agreed normal time-wage. The piece-rates are reckoned so that can be achieved. But in effect this was implicit everywhere as when the average wages in a particular mill were lower than elsewhere for reasons not connected with the quality of labour (e.g. because of antiquated machinery or the low quality of the cotton used), the men demanded "allowances" to raise their wages to the normal level. [4]

In 1893, the Brooklands Agreement was entered into by masters and men in the cotton spinning industry. Under this agreement advances and reductions could not exceed 5% or succeed one another by a shorter period than twelve months and must be preceded by a consultation or 'conference'. Usually the changes were between 5% or 2.50%. The men agreed that formal conciliation would take place between the interested parties before a strike broke out. [4] [14]

James Hargreaves was an English weaver, carpenter and inventor who lived and worked in Lancashire, England. Hargreaves is credited with inventing the spinning jenny in 1764.

The spinning jenny is a multi-spindle spinning frame, and was one of the key developments in the industrialisation of textile manufacturing during the early Industrial Revolution. It was invented in 1764–1765 by James Hargreaves in Stan hill, Oswaldtwistle, Lancashire in England.

A power loom is a mechanized loom, and was one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. The first power loom was designed and patented in 1785 by Edmund Cartwright. It was refined over the next 47 years until a design by the Howard and Bullough company made the operation completely automatic. This device was designed in 1834 by James Bullough and William Kenworthy, and was named the Lancashire loom.

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

Textile manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution was centred in south Lancashire and the towns on both sides of the Pennines in the United Kingdom. The main drivers of the Industrial Revolution were textile manufacturing, iron founding, steam power, oil drilling, the discovery of electricity and its many industrial applications, the telegraph and many others. Railroads, steamboats, the telegraph and other innovations massively increased worker productivity and raised standards of living by greatly reducing time spent during travel, transportation and communications.

Samuel Oldknow (1756–1828) was an English cotton manufacturer.

The spinning mule is a machine used to spin cotton and other fibres. They were used extensively from the late 18th to the early 20th century in the mills of Lancashire and elsewhere. Mules were worked in pairs by a minder, with the help of two boys: the little piecer and the big or side piecer. The carriage carried up to 1,320 spindles and could be 150 feet (46 m) long, and would move forward and back a distance of 5 feet (1.5 m) four times a minute.

Platt Brothers, also known as Platt Bros & Co Ltd, was a British company based at Werneth in Oldham, North West England. The company manufactured textile machinery and were iron founders and colliery proprietors. By the end of the 19th century, the company had become the largest textile machinery manufacturer in the world, employing more than 12,000 workers.

Helmshore Mills are two mills built on the River Ogden in Helmshore, Lancashire. Higher Mill was built in 1796 for William Turner, and Whitaker's Mill was built in the 1820s by the Turner family. In their early life they alternated between working wool and cotton. By 1920 they were working shoddy as condensor mule mills; and equipment has been preserved and is still used. The mills closed in 1967 and they were taken over by the Higher Mills Trust, whose trustees included historian and author Chris Aspin and politician Dr Rhodes Boyson, who maintained it as a museum. The mills are said to the most original and best-preserved examples of both cotton spinning and woollen fulling left in the country that are still operational.

Bagley & Wright was a spinning, doubling and weaving company based in Oldham, Lancashire, England. The business, which was active from 1867 until 1924, 'caught the wave' of the cotton-boom that existed following the end of the American Civil War in 1865 and experienced rapid growth in the United Kingdom and abroad.

The Lancashire Loom was a semi-automatic power loom invented by James Bullough and William Kenworthy in 1842. Although it is self-acting, it has to be stopped to recharge empty shuttles. It was the mainstay of the Lancashire cotton industry for a century.

The Amalgamated Association of Operative Cotton Spinners and Twiners, also known as the Amalgamation, was a trade union in the United Kingdom which existed between 1870 and 1970. It represented male mule spinners in the cotton industry.

The Weavers' Triangle is an area of Burnley in Lancashire, England consisting mostly of 19th-century industrial buildings at the western side of town centre clustered around the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. The area has significant historic interest as the cotton mills and associated buildings encapsulate the social and economic development of the town and its weaving industry. From the 1980s, the area has been the focus of major redevelopment efforts.

Bancroft Shed was a weaving shed in Barnoldswick, Lancashire, England, situated on the road to Skipton. Construction was started in 1914 and the shed was commissioned in 1920 for James Nutter & Sons Limited. The mill closed on 22 December 1978 and was demolished. The engine house, chimneys and boilers have been preserved and maintained as a working steam museum. The mill was the last steam-driven weaving shed to be constructed and the last to close.

The more looms system was a productivity strategy introduced in the Lancashire cotton industry, whereby each weaver would manage a greater number of looms. It was an alternative to investing in the more productive Northrop automatic looms in the 1930s. It caused resentment, resulted in industrial action, and failed to achieve any significant cost savings.

"Kissing the shuttle" is the term for a process by which weavers used their mouths to pull thread through the eye of a shuttle when the pirn was replaced. The same shuttles were used by many weavers, and the practice was unpopular. It was outlawed in the U.S. state of Massachusetts in 1911 but continued even after it had been outlawed in Lancashire, England in 1952. The Lancashire cotton industry was loath to invest in hand-threaded shuttles, or in the more productive Northrop automatic looms with self-threading shuttles, which were introduced in 1902.

Harle Syke mill is a weaving shed in Briercliffe on the outskirts of Burnley, Lancashire, England. It was built on a green field site in 1856, together with terraced houses for the workers. These formed the nucleus of the community of Harle Syke. The village expanded and six other mills were built, including Queen Street Mill.

Steaming or artificial humidity was the process of injecting steam from boilers into cotton weaving sheds in Lancashire, England, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The intention was to prevent breakages in short-staple Indian Surat cotton which was introduced in 1862 during a blockade of American cotton at the time of the American Civil War. There was considerable concern about the health implications of steaming. Believed to cause ill health, this practice became the subject of much campaigning and investigation from the 1880s to the 1920s. A number of Acts of Parliament imposed modifications.

Ellen Hooton was a ten-year-old girl from Wigan who gave testimony to the Central Board of His Majesty's Commissioners for inquiring into the Employment of Children in Factories, 1833. She had been working for several years at a spinning frame, in a cotton mill along with other children. She worked from 5.30 am till 8 pm, six days a week and nine hours on a Saturday. She absconded at least 10 times and was punished by her overseers.

The Bolton and District Operative Cotton Spinners' Provincial Association (BOCSPA) was a trade union representing cotton spinners across central Lancashire, in England. It was the most important union of cotton spinners, and dominated the Spinners' Amalgamation.