Gnaeus Julius Agricola was a Roman general and politician responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. Born to a political family of senatorial rank, Agricola began his military career as a military tribune under governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus. In his subsequent career, he served in a variety of political positions in Rome. In 64, he was appointed quaestor in Asia province. Two years later, he was appointed Plebeian Tribune, and in 68, he was made praetor. During the Year of the Four Emperors in 69, he supported Vespasian, general of the Syrian army, in his bid for the throne.

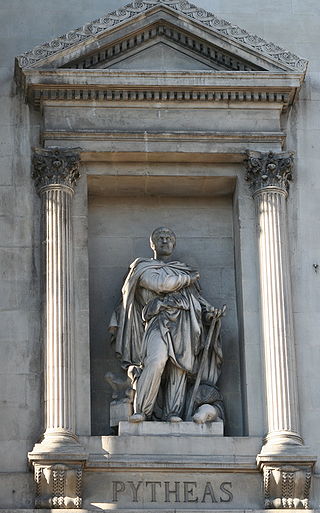

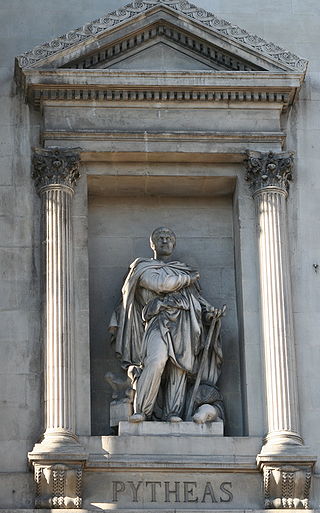

Pytheas of Massalia was a Greek geographer, explorer and astronomer from the Greek colony of Massalia. He made a voyage of exploration to Northern Europe in about 325 BC, but his account of it, known widely in antiquity, has not survived and is now known only through the writings of others.

The Suebi were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own names such as the Marcomanni, Quadi, Hermunduri, Semnones, and Lombards. New groupings formed later, such as the Alamanni and Bavarians, and two kingdoms in the Migration Period were simply referred to as Suebian.

The Roman conquest of Britain was the Roman Empire's conquest of most of the island of Britain, which was inhabited by the Celtic Britons. It began in earnest in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius, and was largely completed in the southern half of Britain by AD 87, when the Stanegate was established. The conquered territory became the Roman province of Britannia. Attempts to conquer northern Britain (Caledonia) in the following centuries were not successful.

The Menapii were a Belgic tribe dwelling near the North Sea, around present-day Cassel, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

The Lingones were a Gallic tribe of the Iron Age and Roman periods. They dwelled in the region surrounding the present-day city of Langres, between the provinces of Gallia Lugdunensis and Gallia Belgica.

The Sicambri, also known as the Sugambri or Sicambrians, were a Germanic people who during Roman times lived on the east bank of the river Rhine, in what is now Germany, near the border with the Netherlands. They were first reported by Julius Caesar, who described them as Germanic (Germani), though he did not necessarily define this in terms of language.

The Selgovae were a Celtic tribe of the late 2nd century AD who lived in what is now Kirkcudbrightshire and Dumfriesshire, on the southern coast of Scotland. They are mentioned briefly in Ptolemy's Geography, and there is no other historical record of them. Their cultural and ethnic affinity is commonly assumed to have been Brittonic.

Túathal Techtmar, son of Fíachu Finnolach, was a High King of Ireland, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition. He is said to be the ancestor of the Uí Néill and Connachta dynasties through his grandson Conn of the Hundred Battles. The name may also have originally referred to an eponymous deity, possibly even a local version of the Gaulish Toutatis.

The Angrivarii were a Germanic people of the early Roman Empire, who lived in what is now northwest Germany near the middle of the Weser river. They were mentioned by the Roman authors Tacitus and Ptolemy.

The Gutones were a Germanic people who were reported by Roman era writers in the 1st and 2nd centuries to have lived in what is now Poland. The most accurate description of their location, by the geographer Ptolemy, placed them east of the Vistula River.

The Novantae were people of the Iron age, as recorded in Ptolemy's Geography. The Novantae are thought to have lived in what is now Galloway and Carrick, in southwesternmost Scotland.

Drumanagh is a headland near the village of Loughshinny, in the north east of Dublin, Ireland. It features an early 19th-century Martello tower and a large Iron Age promontory fort which has produced Roman artefacts.

The Gangani (Γαγγανοι) were a people of ancient Ireland who are referred to in Ptolemy's 2nd-century Geography as living in the south-west of the island, probably near the mouth of the River Shannon, between the Auteini to the north and the Uellabori to the south. There appears to have been a people of the same name in north-west Wales, as Ptolemy calls the Llŷn Peninsula the "promontory of the Gangani".

The Vacomagi were a people of ancient Britain, known only from a single mention of them by the geographer Claudius Ptolemy. Their principal places are known from Ptolemy's map c.150 of Albion island of Britannia – from the First Map of Europe.

Daedala or Daidala was a city of the Rhodian Peraea in ancient Caria, or a small place, as Stephanus of Byzantium says, on the authority of Strabo.

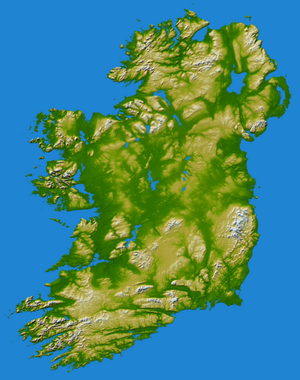

Hiberno-Roman relations refers to the relationships which existed between Ireland (Hibernia) and the ancient Roman Empire, which lasted from the 1st century BC to the 5th century AD in Western Europe. Ireland was one of the few areas of western Europe not conquered by Rome.

The Marsaci or Marsacii were a tribe in Roman imperial times, who lived within the area of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta, under Roman domination.

Lough Boderg is a lake on the River Shannon in County Roscommon and County Leitrim, Ireland.

Ptolemy's map of Ireland is a part of Ptolemy's "first European map" in the series of maps included in his Geography, which he compiled in the second century AD in Roman Egypt and which is the oldest surviving map of Ireland. Ptolemy's own maps do not survive, but is known from manuscript copies made during the Middle Ages and from the text of the Geography, which gives coordinates and place names. Ptolemy almost certainly never visited Ireland, but compiled the map based on military, trader and traveller reports and his own mathematical calculations. Given the creation process, the time period involved and the fact that the Greeks and Romans had limited contact with Ireland, it is considered remarkably accurate.