Child sex tourism (CST) is tourism for the purpose of engaging in the prostitution of children, which is commercially facilitated child sexual abuse. The definition of child in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child is "every human being below the age of 18 years". Child sex tourism results in both mental and physical consequences for the exploited children, which may include sexually transmitted infections, "drug addiction, pregnancy, malnutrition, social ostracism, and death", according to the State Department of the United States. Child sex tourism, part of the multibillion-dollar global sex tourism industry, is a form of child prostitution within the wider issue of commercial sexual exploitation of children. Child sex tourism victimizes approximately 2 million children around the world. The children who perform as prostitutes in the child sex tourism trade often have been lured or abducted into sexual slavery.

Prostitution in New Zealand, brothel-keeping, living off the proceeds of someone else's prostitution, and street solicitation are legal in New Zealand and have been since the Prostitution Reform Act 2003 came into effect. Coercion of sex workers is illegal. The 2003 decriminalisation of brothels, escort agencies and soliciting, and the substitution of a minimal regulatory model, created worldwide interest; New Zealand prostitution laws are now some of the most liberal in the world.

Prostitution in Thailand is illegal. However, due to police corruption and an economic reliance on prostitution dating back to the Vietnam War, it remains a significant presence in the country. It results from poverty, low levels of education and a lack of employment in rural areas. Prostitutes mostly come from the northeastern (Isan) region of Thailand, from ethnic minorities or from neighbouring countries, especially Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos. UNAIDS in 2019 estimated the total population of sex workers in Thailand to be 43,000.

In Great Britain, the act of engaging in sex as part of an exchange of various sexual services for money is legal, but a number of related activities, including soliciting in a public place, kerb crawling, owning or managing a brothel, pimping and pandering, are illegal. In Northern Ireland, which previously had similar laws, paying for sex became illegal from 1 June 2015.

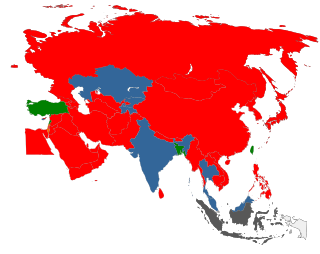

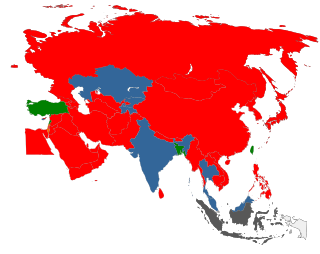

The legality of prostitution in Asia varies by country. There is often a significant difference in Asia between prostitution laws and the practice of prostitution. In 2011, the Asian Commission on AIDS estimated there were 10 million sex workers in Asia and 75 million male customers.

Prostitution in Ireland is legal. However, since March 2017, it has been an offence to buy sex. Third party involvement is also illegal. Since the law that criminalises clients came into being, with the purpose of reducing the demand for prostitution, the number of prosecutions for the purchase of sex increased from 10 to 92 between 2018 and 2020. In a report from UCD's Sexual Exploitation Research Programme the development is called ”a promising start in interrupting the demand for prostitution.”

Prostitution in Finland is legal, but soliciting in a public place and organised prostitution are illegal. According to a 2010 TAMPEP study, 69% of prostitutes working in Finland are migrants. As of 2009, there was little "visible" prostitution in Finland as it was mostly limited to private residences and nightclubs in larger metropolitan areas.

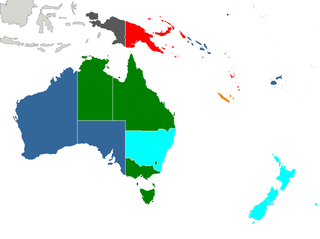

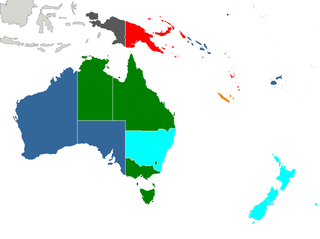

Prostitution or sex work in Australia is governed by state and territory laws, which vary considerably. Federal legislation also affects some aspects of sex work throughout Australia, and of Australian citizensabroad.

Prostitution in Belize is legal, but the buying of sexual services is not. Associated activities such as operating a brothel, loitering for the purposes of prostitution and soliciting sex are also illegal.

Current laws passed by the Parliament of Canada in 2014 make it illegal to purchase or advertise sexual services and illegal to live on the material benefits from sex work. The law officially enacted criminal penalties for "Purchasing sexual services and communicating in any place for that purpose."

Prostitution in Sierra Leone is legal and commonplace. Soliciting and 3rd party involvement are prohibited by the Sexual Offences Act 2012. UNAIDS estimate there are 240,000 prostitutes in the country. They are known locally as 'serpents' because of the hissing noise they use to attract clients.

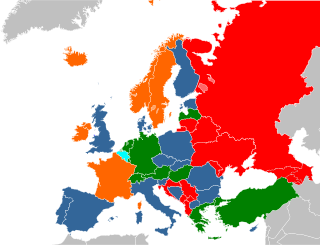

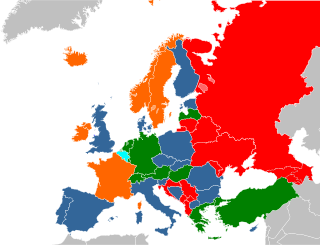

The legality of prostitution in Europe varies by country.

Prostitution in Scotland has been similar to that in England under the State of Union, but since devolution, the new Scottish Parliament has pursued its own policies.

There are a number of sexual offences under the law of England and Wales, the law of Scotland, and the law of Northern Ireland.

Prostitution laws varies widely from country to country, and between jurisdictions within a country. At one extreme, prostitution or sex work is legal in some places and regarded as a profession, while at the other extreme, it is considered a severe crime punishable by death in some other places.

The decriminalization of sex work is the removal of criminal penalties for sex work. Sex work, the consensual provision of sexual services for money or goods, is criminalized in most countries. Decriminalization is distinct from legalization.

Prostitution in Oceania varies greatly across the region. In American Samoa, for instance, prostitution is illegal, whereas in New Zealand most aspects of the trade are decriminalised.

The Nordic Criminal Model approach to sex work, also marketed as the end demand, equality model, neo-abolitionism, Nordic and Swedish model, is an approach to sex work that criminalises clients, third parties and many ways sex workers operate. This approach to criminalising sex work was developed in Sweden in 1999 on the debated radical feminist position that all sex work is sexual servitude and no person can consent to engage in commercial sexual services. The main objective of the model is to abolish the sex industry by punishing the purchase of sexual services. The model was also original developed to make working in the sex industry more difficult, as Ann Martin said when asked about their role in developing the model - "I think of course the law has negative consequences for women in prostitution but that’s also some of the effect that we want to achieve with the law... It shouldn’t be as easy as it was before to go out and sell sex."

Laura Lee was an Irish sex worker and civil rights activist, who became a campaigner for the rights of people in the sex industry.

There are a number of sexual offences under the law of Northern Ireland.