William Shakespeare was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon". His extant works, including collaborations, consist of some 39 plays, 154 sonnets, three long narrative poems and a few other verses, some of uncertain authorship. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright. Shakespeare remains arguably the most influential writer in the English language, and his works continue to be studied and reinterpreted.

Shakespearean tragedy is the designation given to most tragedies written by playwright William Shakespeare. Many of his history plays share the qualifiers of a Shakespearean tragedy, but because they are based on real figures throughout the history of England, they were classified as "histories" in the First Folio. The Roman tragedies—Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra and Coriolanus—are also based on historical figures, but because their sources were foreign and ancient, they are almost always classified as tragedies rather than histories. Shakespeare's romances were written late in his career and published originally as either tragedy or comedy. They share some elements of tragedy, insofar as they feature a high-status central character, but they end happily like Shakespearean comedies. Almost three centuries after Shakespeare's death, the scholar F. S. Boas also coined a fifth category, the "problem play," for plays that do not fit neatly into a single classification because of their subject matter, setting, or ending. Scholars continue to disagree on how to categorize some Shakespearean plays.

Cymbeline, also known as The Tragedie of Cymbeline or Cymbeline, King of Britain, is a play by William Shakespeare set in Ancient Britain and based on legends that formed part of the Matter of Britain concerning the early historical Celtic British King Cunobeline. Although it is listed as a tragedy in the First Folio, modern critics often classify Cymbeline as a romance or even a comedy. Like Othello and The Winter's Tale, it deals with the themes of innocence and jealousy. While the precise date of composition remains unknown, the play was certainly produced as early as 1611.

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio. A masque involved music, dancing, singing and acting, within an elaborate stage design, in which the architectural framing and costumes might be designed by a renowned architect, to present a deferential allegory flattering to the patron. Professional actors and musicians were hired for the speaking and singing parts. Masquers who did not speak or sing were often courtiers: the English queen Anne of Denmark frequently danced with her ladies in masques between 1603 and 1611, and Henry VIII and Charles I of England performed in the masques at their courts. In the tradition of masque, Louis XIV of France danced in ballets at Versailles with music by Jean-Baptiste Lully.

Tragicomedy is a literary genre that blends aspects of both tragic and comic forms. Most often seen in dramatic literature, the term can describe either a tragic play which contains enough comic elements to lighten the overall mood or a serious play with a happy ending. Tragicomedy, as its name implies, invokes the intended response of both the tragedy and the comedy in the audience, the former being a genre based on human suffering that invokes an accompanying catharsis and the latter being a genre intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter.

Drama was introduced to Britain from Europe by the Romans, and auditoriums were constructed across the country for this purpose.

In the First Folio, the plays of William Shakespeare were grouped into three categories: comedies, histories, and tragedies; and modern scholars recognise a fourth category, romance, to describe the specific types of comedy that appear in Shakespeare's later works.

This article presents a possible chronological listing of the composition of the plays of William Shakespeare.

John Fletcher was an English playwright. Following William Shakespeare as house playwright for the King's Men, he was among the most prolific and influential dramatists of his day; during his lifetime and in the Stuart Restoration, his fame rivalled Shakespeare's. Fletcher collaborated in writing plays, chiefly with Francis Beaumont or Philip Massinger, but also with Shakespeare and others.

The Complete Works of William Shakespeare is the standard name given to any volume containing all the plays and poems of William Shakespeare. Some editions include several works that were not completely of Shakespeare's authorship, such as The Two Noble Kinsmen, which was a collaboration with John Fletcher; Pericles, Prince of Tyre, the first two acts of which were likely written by George Wilkins; or Edward III, whose authorship is disputed.

David Martin Bevington was an American literary scholar. He was the Phyllis Fay Horton Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in the Humanities and in English Language & Literature, Comparative Literature, and the college at the University of Chicago, where he taught since 1967, as well as chair of Theatre and Performance Studies. "One of the most learned and devoted of Shakespeareans," so called by Harold Bloom, he specialized in British drama of the Renaissance, and edited and introduced the complete works of William Shakespeare in both the 29-volume, Bantam Classics paperback editions and the single-volume Longman edition. After accomplishing this feat, Bevington was often cited as the only living scholar to have personally edited Shakespeare's complete corpus.

Elizabethan literature refers to bodies of work produced during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603), and is one of the most splendid ages of English literature. In addition to drama and the theatre, it saw a flowering of poetry, with new forms like the sonnet, the Spenserian stanza, and dramatic blank verse, as well as prose, including historical chronicles, pamphlets, and the first English novels. Major writers include William Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser, Christopher Marlowe, Richard Hooker, Ben Jonson, Philip Sidney and Thomas Kyd.

Tales from Shakespeare is an English children's book written by the siblings Charles and Mary Lamb in 1807, intended "for the use of young persons" while retaining as much Shakespearean language as possible. Mary Lamb was responsible for retelling the comedies and Charles the tragedies. They omitted the more complex historical tales, including all Roman plays, and modified those they chose to retell in a manner sensitive to the needs of young children, but without resorting to actual censoring. However, subplots and sexual references were removed. They wrote the preface together.

Shakespeare's plays are a canon of approximately 39 dramatic works written by the English poet, playwright, and actor William Shakespeare. The exact number of plays as well as their classifications as tragedy, history, comedy, or otherwise is a matter of scholarly debate. Shakespeare's plays are widely regarded as among the greatest in the English language and are continually performed around the world. The plays have been translated into every major living language.

Dumbshow, also dumb show or dumb-show, is defined by the Oxford Dictionary of English as "gestures used to convey a meaning or message without speech; mime." In the theatre the word refers to a piece of dramatic mime in general, or more particularly a piece of action given in mime within a play "to summarise, supplement, or comment on the main action".

The Oxford Shakespeare is the range of editions of William Shakespeare's works produced by Oxford University Press. The Oxford Shakespeare is produced under the general editorship of Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor.

Beautiful Stories from Shakespeare is a 1907 collection published by E. Nesbit with the intention of entertaining young readers and retelling William Shakespeare's plays in a way they could be easily understood by younger readers. She also included a brief Shakespeare biography, a pronunciation guide to some of the more difficult names and a list of famous quotations, arranged by subject. Some editions are entitled Beautiful Stories from Shakespeare for Children.

Women in Shakespeare is a topic within the especially general discussion of Shakespeare's dramatic and poetic works. Main characters such as Dark Lady of the sonnets have elicited a substantial amount of criticism, which received added impetus during the second-wave feminism of the 1960s. A considerable number of book-length studies and academic articles investigate the topic, and several moons of Uranus are named after women in Shakespeare.

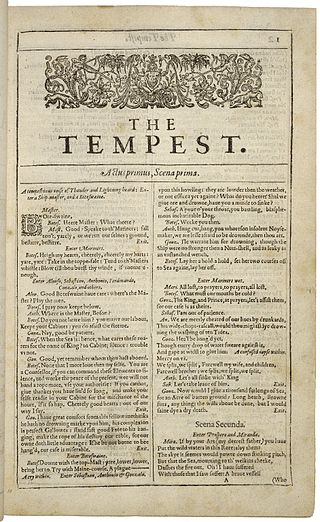

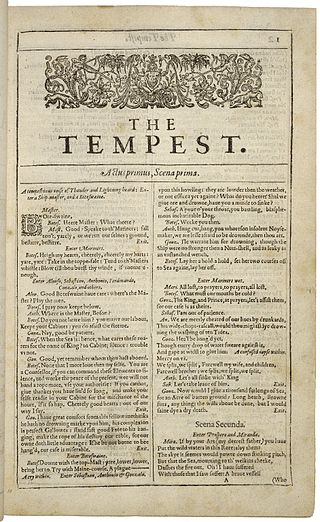

The Tempest is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that he wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, the rest of the story is set on a remote island, where Prospero, a wizard, lives with his daughter Miranda, and his two servants: Caliban, a savage monster figure, and Ariel, an airy spirit. The play contains music and songs that evoke the spirit of enchantment on the island. It explores many themes, including magic, betrayal, revenge, and family. In Act IV, a wedding masque serves as a play-within-a-play, and contributes spectacle, allegory, and elevated language.

Georgia Shakespeare was a professional, not-for-profit theatre company located in Atlanta, Georgia, in the United States on the campus of Oglethorpe University from 1985-2014. Georgia Shakespeare produced three plays annually, primarily between June and November. Twelve educational programs were developed in the history of Georgia Shakespeare. These programs included "The High School Tour", a "High School Acting Competition", "Camp Shakespeare", a "High School Conservatory", a "No Fear Shakespeare" training program for educators, after school residencies, school tours, student matinees, classes for professionals, and in-school workshops. At its peak, it welcomed 60,000 patrons annually to its performances.