Related Research Articles

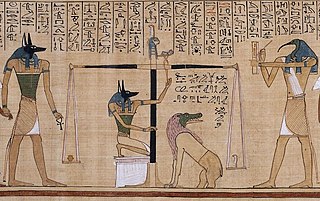

Anubis or Inpu, Anpu in Ancient Egyptian is the Greek name of the god of death, mummification, embalming, the afterlife, cemeteries, tombs, and the Underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head. Archeologists have identified Anubis's sacred animal as an Egyptian canid, the African golden wolf. The African wolf was formerly called the "African golden jackal", until a 2015 genetic analysis updated the taxonomy and the common name for the species. As a result, Anubis is often referred to as having a "jackal" head, but this "jackal" is now more properly called a "wolf".

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay further if kept in cool and dry conditions. Some authorities restrict the use of the term to bodies deliberately embalmed with chemicals, but the use of the word to cover accidentally desiccated bodies goes back to at least 1615 AD.

Egyptology is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious practices in the 4th century AD. A practitioner of the discipline is an "Egyptologist". In Europe, particularly on the Continent, Egyptology is primarily regarded as being a philological discipline, while in North America it is often regarded as a branch of archaeology.

The ancient Egyptians believed that a soul was made up of many parts. In addition to these components of the soul, there was the human body.

The Book of the Dead is an ancient Egyptian funerary text generally written on papyrus and used from the beginning of the New Kingdom to around 50 BCE. The original Egyptian name for the text, transliterated rw nw prt m hrw, is translated as Book of Coming Forth by Day or Book of Emerging Forth into the Light. "Book" is the closest term to describe the loose collection of texts consisting of a number of magic spells intended to assist a dead person's journey through the Duat, or underworld, and into the afterlife and written by many priests over a period of about 1,000 years.

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

Tomb KV60 is an ancient Egyptian tomb in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt. It was discovered by Howard Carter in 1903, and re-excavated by Donald P. Ryan in 1989. It is one of the more perplexing tombs of the Theban Necropolis, due to the uncertainty over the identity of one female mummy found there (KV60A). She is identified by some, such as Egyptologist Elizabeth Thomas, to be that of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Hatshepsut; This identification is advocated for by Zahi Hawass.

Tomb KV46 in the Valley of the Kings is the tomb of Yuya and his wife Tjuyu, the parents of Queen Tiye and Anen. It was discovered in February 1905 by James E. Quibell under the sponsorship of Theodore M. Davis. Despite robberies in antiquity, the undecorated tomb preserved a great deal of its original contents including chests, beds, chairs, a chariot, and numerous storage jars. Additionally, the riffled but undamaged mummies of Yuya and Tjuyu were found within their disturbed coffin sets. Prior to the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, this was considered to be one of the greatest discoveries in Egyptology.

Yuya was a powerful ancient Egyptian courtier during the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. He was married to Tjuyu, an Egyptian noblewoman associated with the royal family, who held high offices in the governmental and religious hierarchies. Their daughter, Tiye, became the Great Royal Wife of Amenhotep III. Yuya and Tjuyu are known to have had a son named Anen, who carried the titles "Chancellor of Lower Egypt", "Second Prophet of Amun","sm-priest of Heliopolis, and "Divine Father".

Tjuyu was an Egyptian noblewoman and the mother of queen Tiye, and the wife of Yuya. She is the grandmother of Akhenaten, and great grandmother of Tutankhamun.

The medicine of the ancient Egyptians is some of the oldest documented. From the beginnings of the civilization in the late fourth millennium BC until the Persian invasion of 525 BC, Egyptian medical practice went largely unchanged and included simple non-invasive surgery, setting of bones, dentistry, and an extensive set of pharmacopoeia. Egyptian medical thought influenced later traditions, including the Greeks.

Faiyum is a city in Middle Egypt. Located 100 kilometres southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyum Governorate. Originally called Shedet in Egyptian, the Greeks called it in Koinē Greek: Κροκοδειλόπολις, romanized: Krokodilópolis, and later Byzantine Greek: Ἀρσινόη, romanized: Arsinoë. It is one of Egypt's oldest cities due to its strategic location.

This is a glossary of ancient Egypt artifacts.

An embalming cache is a collection of material that was used by the ancient Egyptians in the mummification process and then buried either with or separately from the body. It is believed that because the materials had come in contact with the body, they had possibly absorbed part of it, and needed to be buried in order for the body to be complete in the afterlife.

Animal mummification was common in ancient Egypt. They mummified various animals. It was an enormous part of Egyptian culture, not only in their role as food and pets, but also for religious reasons. They were typically mummified for four main purposes—to allow beloved pets to go on to the afterlife, to provide food in the afterlife, to act as offerings to a particular god, and because some were seen as physical manifestations of specific deities that the Egyptians worshipped. Bastet, the cat goddess, is an example of one such deity. In 1888, an Egyptian farmer digging in the sand near Istabl Antar discovered a mass grave of felines, ancient cats that were mummified and buried in pits at great numbers.

The Book of Traversing Eternity is an ancient Egyptian funerary text used primarily in the Roman period of Egyptian history. The earliest known copies date to the preceding Ptolemaic Period, making it most likely that the book was composed at that time.

The Egyptian dog Abuwtiyuw, also transcribed as Abutiu, was one of the earliest documented domestic animals whose name is known. He is believed to have been a royal guard dog who lived in the Sixth Dynasty (2345–2181 BC), and received an elaborate ceremonial burial in the Giza Necropolis at the behest of a pharaoh whose name is unknown.

The Ancient Egyptian anatomical studies is an article about the history of anatomy within ancient Egypt.

The Apis Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian artifact, the work of scribes upon papyrus, concerning the Apis bull.

Tayt was an Egyptian goddess. Some attest her husband was Neper while others state she was possibly the consort of Hedjhotep.

References

- 1 2 Robert (Bob) Brier, Ronald S. Wade - Surgical Procedures during ancient Egyptian Mummification Chungará (Arica) v.33 n.1 Arica ene. 2001 [Retrieved 2015-06-29] (ed. see also this link)

- 1 2 3 4 G.E.Smith & W.R.Dawson (2013-10-28). Egyptian Mummies Hb (first page of Chapter III). Routledge, 28 Oct 2013, 256 pages. ISBN 978-1136188855 . Retrieved 2015-06-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christina Riggs (2014-06-05). Unwrapping Ancient Egypt: The Shroud, the Secret and the Sacred (p.81). Bloomsbury Publishing 5 Jun 2014, 336 pages. ISBN 978-0857855077 . Retrieved 2015-07-01.(ed. this source used to add < some Demotic notations, Papyrus of the Embalming Ritual, eleven acts, wrapping, >

- 1 2 Riggs, Christina (2010-01-22). Funerary rituals (Ptolemaic and Roman Periods) In Jacco Dieleman, Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. 1. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Retrieved 2015-06-29.(permalink [ permanent dead link ])

- ↑ Carol Andrews - Egyptian Mummies Harvard University Press 2004 (reprint, revised), 96 pages, ISBN 0674013913 [Retrieved 2015-06-30]

- ↑ Anne Burton - Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary (p.267) Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l'Empire romain, BRILL, 1973, 301 pages, ISBN 9004035141 [Retrieved 2015-06-30]