Djoser was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom, and was the founder of that epoch. He is also known by his Hellenized names Tosorthros and Sesorthos. He was the son of King Khasekhemwy and Queen Nimaathap, but whether he was also the direct successor to their throne is unclear. Most Ramesside king lists identify a king named Nebka as preceding him, but there are difficulties in connecting that name with contemporary Horus names, so some Egyptologists question the received throne sequence. Djoser is known for his step pyramid, which is the earliest colossal stone building in ancient Egypt.

Khufu or Cheops was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty, in the first half of the Old Kingdom period. Khufu succeeded his father Sneferu as king. He is generally accepted as having commissioned the Great Pyramid of Giza, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but many other aspects of his reign are poorly documented.

The Turin King List, also known as the Turin Royal Canon, is an ancient Egyptian hieratic papyrus thought to date from the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II, now in the Museo Egizio in Turin. The papyrus is the most extensive list available of kings compiled by the ancient Egyptians, and is the basis for most chronology before the reign of Ramesses II.

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt is considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom by Egyptologists. It often is combined with the Eleventh, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth dynasties under the group title, Middle Kingdom. Some scholars only consider the 11th and 12th dynasties to be part of the Middle Kingdom.

The Westcar Papyrus is an ancient Egyptian text containing five stories about miracles performed by priests and magicians. In the papyrus text, each of these tales are told at the royal court of king Khufu (Cheops) by his sons. The story in the papyrus usually is rendered in English as, "King Cheops and the Magicians" and "The Tale of King Cheops' Court". In German, into which the text of the Westcar Papyrus was first translated, it is rendered as Die Märchen des Papyrus Westcar.

Johann Peter Adolf Erman was a German Egyptologist and lexicographer.

The Prophecy of Neferti is one of the few surviving literary texts from ancient Egypt. The story is set in the Old Kingdom, under the reign of King Snefru. However, the text should be attributed to an individual named Neferyt, who most likely composed it at the beginning of the Twelfth Dynasty. The nature of the literary text is argued upon. There are a number of different theories stating that the literature is a historical romance in pseudo-prophetic form, political literature, religious motivation as well as a literary text created to change and improve the situation in Egypt during the Twelfth Dynasty.

Sekhemre Khutawy Amenemhat Sobekhotep was an Egyptian pharaoh of the early 13th Dynasty.

Djedi is the name of a fictional ancient Egyptian magician appearing in the fourth chapter of a story told in the legendary Westcar Papyrus. He is said to have worked wonders during the reign of king (pharaoh) Khufu.

Nebka is the throne name of an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Third Dynasty during the Old Kingdom period, in the 27th century BCE. He is thought to be identical with the Hellenized name Νεχέρωχις recorded by the Egyptian priest Manetho of the much later Ptolemaic period.

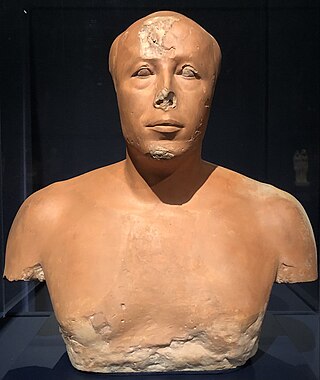

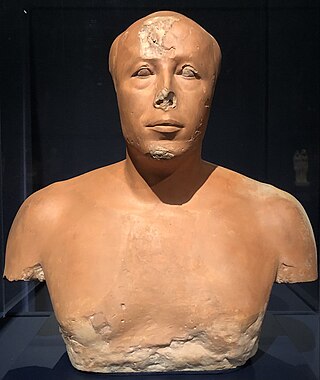

Ankhhaf was an Egyptian prince and served as an overseer during the reign of the Pharaoh Khufu, who is thought to have been Ankhhaf's half-brother. One of Ankhaf's titles is also as a vizier, but it is unknown which pharaoh he would have held this title under. He lived during Egypt's 4th Dynasty.

Ancient Egyptian literature was written in the Egyptian language from ancient Egypt's pharaonic period until the end of Roman domination. It represents the oldest corpus of Egyptian literature. Along with Sumerian literature, it is considered the world's earliest literature.

Sneferu, well known under his Hellenized name Soris, was the founding pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt during the Old Kingdom. Estimates of his reign vary, with for instance The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt suggesting a reign from around 2613 to 2589 BC, a reign of 24 years, while Rolf Krauss suggests a 30-year reign, and Rainer Stadelmann a 48-year reign. He built at least three pyramids that survive to this day and introduced major innovations in the design and construction of pyramids.

Djedi was an Egyptian prince who lived during Fourth Dynasty of Egypt. He was a son of Prince Rahotep and Nofret, grandson of pharaoh Sneferu and nephew of pharaoh Khufu. He had two brothers and three sisters. He is depicted in the tomb chapels of his parents and bears there the title "King's Acquaintance".

Kagemni I was an ancient Egyptian who lived from the end of the 3rd Dynasty to the beginning of the 4th Dynasty. He was a vizier to both Pharaoh Huni and Pharaoh Sneferu.

Baufra is the name of an alleged son of the ancient Egyptian king (pharaoh) Khufu from the 4th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. He is known from a story in the Papyrus Westcar and from a rock inscription at Wadi Hammamat. He is neither contemporarily nor archaeologically attested, which makes his historical figure disputable to scholars up to this day.

This page list topics related to ancient Egypt.

Ubaoner is the name of a fictitious ancient Egyptian magician appearing in the second chapter of a story told in the legendary Westcar Papyrus. He is said to have worked wonders during the reign of king (pharaoh) Nebka.

Rededjet is the name of a fictitious ancient Egyptian woman appearing as the heroic character in a story told in the legendary Westcar Papyrus. She is said to have fulfilled a prophecy by giving birth to three future kings that was forecast during the reign of Khufu by a magician named Dedi.

Netjerkare Siptah was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the seventh and last ruler of the Sixth Dynasty. Alternatively some scholars classify him as the first king of the Seventh or Eighth Dynasty. As the last king of the 6th Dynasty, Netjerkare Siptah is considered by some Egyptologists to be the last king of the Old Kingdom period.