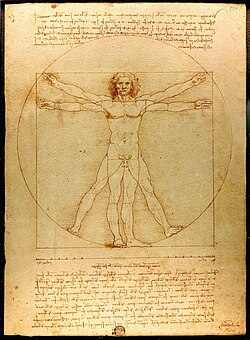

Body proportions is the study of artistic anatomy, which attempts to explore the relation of the elements of the human body to each other and to the whole. These ratios are used in depictions of the human figure and may become part of an artistic canon of body proportion within a culture. Academic art of the nineteenth century demanded close adherence to these reference metrics and some artists in the early twentieth century rejected those constraints and consciously mutated them.