The Llangollen Canal is a navigable canal crossing the border between England and Wales. The waterway links Llangollen in Denbighshire, north Wales, with Hurleston in south Cheshire, via the town of Ellesmere, Shropshire. The name, which was coined in the 1980s, is a modern designation for parts of the historic Ellesmere Canal and the Llangollen navigable feeder, both of which became part of the Shropshire Union Canals in 1846.

Quarry Bank Mill in Styal, Cheshire, England, is one of the best preserved textile factories of the Industrial Revolution. Built in 1784, the cotton mill is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II* listed building. Quarry Bank Mill was established by Samuel Greg, and was notable for innovations both in machinery and also in its approach to labour relations, the latter largely as a result of the work of Greg's wife, Hannah Lightbody. The family took a somewhat paternalistic attitude toward the workers, providing medical care for all and limited education to the children, but all laboured roughly 72 hours per week until 1847 when a new law shortened the hours.

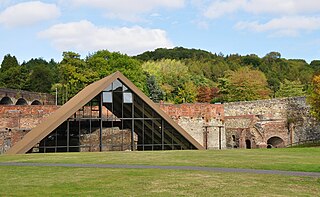

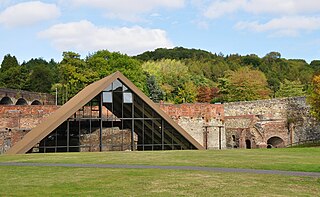

Coalbrookdale is a village in the Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called the Gorge.

The Stort Navigation is the canalised section of the River Stort running 22 kilometres (14 mi) from the town of Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, downstream to its confluence with the Lee Navigation at Feildes Weir near Rye House, Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire.

Blists Hill Victorian Town is an open-air museum built on a former industrial complex located in the Madeley area of Telford, Shropshire, England. The museum attempts to recreate the sights, sounds and smells of a Victorian Shropshire town in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is one of ten museums operated by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust.

Stonehouse is a town in the Stroud District of Gloucestershire in southwestern England.

The Shrewsbury Canal was a canal in Shropshire, England. Authorised in 1793, the main line from Trench to Shrewsbury was fully open by 1797, but it remained isolated from the rest of the canal network until 1835, when the Birmingham and Liverpool Junction Canal built the Newport Branch from Norbury Junction to a new junction with the Shrewsbury Canal at Wappenshall. After ownership passed to a series of railway companies, the canal was officially abandoned in 1944; many sections have disappeared, though some bridges and other structures can still be found. There is an active campaign to preserve the remnants of the canal and to restore the Norbury to Shrewsbury line to navigation.

London's architectural heritage involves many architectural styles from different historical periods. London's architectural eclecticism stems from its long history, continual redevelopment, destruction by the Great Fire of London and The Blitz, and state recognition of private property rights which have limited large scale state planning. This sets London apart from other European capitals such as Paris and Rome which are more architecturally homogeneous. London's architecture ranges from the Romanesque central keep of The Tower of London, the great Gothic church of Westminster Abbey, the Palladian royal residence Queen's House, Christopher Wren's Baroque masterpiece St Paul's Cathedral, the High Victorian Gothic of The Palace of Westminster, the industrial Art Deco of Battersea Power Station, the post-war Modernism of The Barbican Estate and the Postmodern skyscraper 30 St Mary Axe 'The Gherkin'.

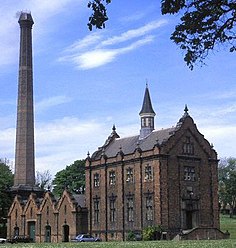

The Leeds Industrial Museum at Armley Mills is a museum of industrial heritage located in Armley, near Leeds, in West Yorkshire, Northern England. The museum includes collections of textile machinery, railway equipment and heavy engineering amongst others.

Cast-iron architecture is the use of cast iron in buildings and objects, ranging from bridges and markets to warehouses, balconies and fences. Refinements developed during the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century made cast iron relatively cheap and suitable for a range of uses, and by the mid-19th century it was common as a structural material, and particularly for elaborately patterned architectural elements such as fences and balconies, until it fell out of fashion after 1900 as a decorative material, and was replaced by modern steel and concrete for structural purposes.

Frog Island is an inner city area of Leicester, England, so named because it lies between the River Soar and the Soar Navigation. Frog Island is adjacent to the Woodgate area to the north, and Northgates to the South. The population of the island was at the 2011 census in the Abbey ward of Leicester City Council.

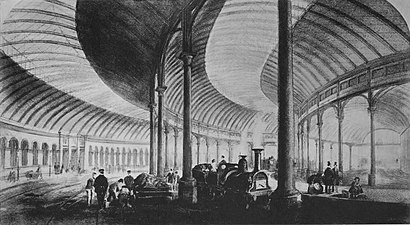

The architecture of Manchester demonstrates a rich variety of architectural styles. The city is a product of the Industrial Revolution and is known as the first modern, industrial city. Manchester is noted for its warehouses, railway viaducts, cotton mills and canals – remnants of its past when the city produced and traded goods. Manchester has minimal Georgian or medieval architecture to speak of and consequently has a vast array of 19th and early 20th-century architecture styles; examples include Palazzo, Neo-Gothic, Venetian Gothic, Edwardian baroque, Art Nouveau, Art Deco and the Neo-Classical.

The Wombridge Canal was a tub-boat canal in Shropshire, England, built to carry coal and iron ore from mines in the area to the furnaces where the iron was extracted. It opened in 1788, and parts of it were taken over by the Shrewsbury Canal Company in 1792, who built an inclined plane at Trench. It lowered tub boats 75 feet (23 m), and remained in operation until 1921, becoming the last operational canal inclined plane in the country. The canal had been little used since 1919, and closed with the closure of the plane.

Hanna, Donald and Wilson were a Scottish engineering and shipbuilding firm which flourished in the Victorian era.

The Hope Village Historic District is a historic rural mill settlement within Hope Village in Scituate, Rhode Island. Hope Village is located on a bend in the North Pawtuxet River in the southeastern corner of Scituate. Industrial activity has occurred in Hope Village since the mid-eighteenth century. Surviving industrial and residential buildings in the Historic District date back to the early 19th century. The village center sits at junction of Main Street and North Road. Hope Village radiates out from the center with houses on several smaller side streets in a compact configuration. Currently there is little commercial or industrial activity in Hope Village and none in the Historic District. The present stone mill building on the south side of Hope Village was built in 1844 by Brown & Ives of Providence, expanded in 1871 and modified in 1910. Approximately one quarter of the village's current housing stock was built as mill worker housing by various owners of Hope Mill.

The St Pancras Basin, also known as St Pancras Yacht Basin, is part of the Regent's Canal in the London Borough of Camden, England, slightly to the west of St Pancras Lock. Formerly known as the Midland Railway Basin, the canal basin is owned by Canal & River Trust, and since 1958 has been home to the St Pancras Cruising Club. The basin is affected by the large-scale developments in progress, related to King's Cross Central.

Industrial architecture is the design and construction of buildings serving industry. Such buildings rose in importance with the Industrial Revolution, starting in Britain, and were some of the pioneering structures of modern architecture.

The Museum of the Gorge, originally the Severn Warehouse, is one of the ten museums of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust. It portrays the history of the Ironbridge Gorge and the surrounding area of Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, England.

The Concord Gas Light Company Gasholder House is a historic gasholder house at Gas Street in Concord, New Hampshire. Built in 1888, it is believed to be the only such structure in the United States in which the enclosed gas containment unit is essentially intact. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2018. Since 2012, it has been owned by Liberty Utilities, a gas, water and electric company. In 2022, Liberty struck a deal with the city of Concord and the New Hampshire Preservation Alliance to begin emergency stabilization work on the building, so that planning for protection and future use can continue.

The Bromley-by-Bow gasholders are a group of seven cast iron Victorian gasholders in Twelvetrees Crescent, West Ham and named after nearby Bromley in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets.