Puffballs are a type of fungus featuring a ball-shaped fruit body that bursts on contact or impact, releasing a cloud of dust-like spores into the surrounding area. Puffballs belong to the division Basidiomycota and encompass several genera, including Calvatia, Calbovista and Lycoperdon. The puffballs were previously treated as a taxonomic group called the Gasteromycetes or Gasteromycetidae, but they are now known to be a polyphyletic assemblage.

Secotioid fungi produce an intermediate fruiting body form that is between the mushroom-like hymenomycetes and the closed bag-shaped gasteromycetes, where an evolutionary process of gasteromycetation has started but not run to completion. Secotioid fungi may or may not have opening caps, but in any case they often lack the vertical geotropic orientation of the hymenophore needed to allow the spores to be dispersed by wind, and the basidiospores are not forcibly discharged or otherwise prevented from being dispersed —note—some mycologists do not consider a species to be secotioid unless it has lost ballistospory.

The Boletales are an order of Agaricomycetes containing over 1300 species with a diverse array of fruiting body types. The boletes are the best known members of this group, and until recently, the Boletales were thought to only contain boletes. The Boletales are now known to contain distinct groups of agarics, puffballs, and other fruiting-body types.

Phallaceae is a family of fungi, commonly known as stinkhorns, within the order Phallales. Stinkhorns have a worldwide distribution, but are especially prevalent in tropical regions. They are known for their foul-smelling, sticky spore masses, or gleba, borne on the end of a stalk called the receptaculum. The characteristic fruiting-body structure, a single, unbranched receptaculum with an externally attached gleba on the upper part, distinguishes the Phallaceae from other families in the Phallales. The spore mass typically smells of carrion or dung, and attracts flies, beetles and other insects to help disperse the spores. Although there is great diversity in body structure shape among the various genera, all species in the Phallaceae begin their development as oval or round structures known as "eggs". The appearance of Phallaceae is often sudden, as gleba can erupt from the underground egg and burst open within an hour. According to a 2008 estimate, the family contains 21 genera and 77 species.

The Boletaceae are a family of mushroom-forming fungi, primarily characterised by small pores on the spore-bearing hymenial surface, instead of gills as are found in most agarics. Nearly as widely distributed as the agarics, the family is renowned for hosting some prime edible species highly sought after by mushroom hunters worldwide, such as the cep or king bolete . A number of rare or threatened species are also present in the family, that have become the focus of increasing conservation concerns. As a whole, the typical members of the family are commonly known as boletes.

Lycoperdon perlatum, popularly known as the common puffball, warted puffball, gem-studded puffball or devil's snuff-box, is a species of puffball fungus in the family Agaricaceae. A widespread species with a cosmopolitan distribution, it is a medium-sized puffball with a round fruit body tapering to a wide stalk, and dimensions of 1.5 to 6 cm wide by 3 to 10 cm tall. It is off-white with a top covered in short spiny bumps or "jewels", which are easily rubbed off to leave a netlike pattern on the surface. When mature it becomes brown, and a hole in the top opens to release spores in a burst when the body is compressed by touch or falling raindrops.

The Sclerodermataceae are a family of fungi in the order Boletales, containing several genera of unusual fungi that little resemble boletes. Taxa, which include species commonly known as the ‘hard-skinned puffballs’, ‘earthballs’, or 'earthstars', are widespread in both temperate and tropical regions. The best known members include the earthball Scleroderma citrinum, the dye fungus Pisolithus tinctorius and the 'prettymouths' of the genus Calostoma.

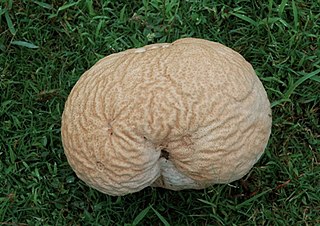

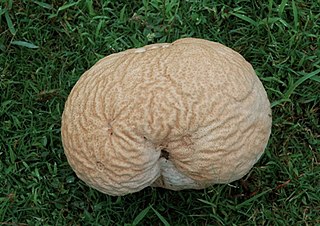

Calvatia craniiformis, commonly known as the brain puffball or the skull-shaped puffball, is a species of puffball fungus in the family Agaricaceae. It is found in Asia, Australia, and North America, where it grows on the ground in open woods. Its name, derived from the same Latin root as cranium, alludes to its resemblance to an animal's brain. The skull-shaped fruit body is 8–20 cm (3–8 in) broad by 6–20 cm (2–8 in) tall and white to tan. Initially smooth, the skin (peridium) develops wrinkles and folds as it matures, cracking and flaking with age. The peridium eventually sloughs away, exposing a powdery yellow-brown to greenish-yellow spore mass. The puffball is edible when the gleba is still white and firm, before it matures to become yellow-brown and powdery. Mature specimens have been used in the traditional or folk medicines of China, Japan, and the Ojibwe as a hemostatic or wound dressing agent. Several bioactive compounds have been isolated and identified from the brain puffball.

Bovista is a genus of fungi commonly known as the true puffballs. It was formerly classified within the now-obsolete order Lycoperdales, which, following a restructuring of fungal taxonomy brought about by molecular phylogeny, has been split; the species of Bovista are now placed in the family Agaricaceae of the order Agaricales. Bovista species have a collectively widespread distribution, and are found largely in temperate regions of the world. Various species have historically been used in homeopathic preparations.

Battarrea phalloides is an inedible species of mushroom in the family Agaricaceae, and the type species of the genus Battarrea. Known in the vernacular as the scaley-stalked puffball, sandy stiltball, or desert stalked puffball, it has a woody, slender, and shaggy or scaly stem that is typically up to 40 centimeters (15.7 in) in length. Although its general appearance resembles an agaric with stem and gills, atop the stem is a spore sac, consisting of a peridium and a powdery internal gleba. In maturity, the spore sac ruptures to release the spores. Battarrea phalloides is found in dry, sandy locations throughout the world, and has been collected from Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America. There is currently some disagreement in the literature as to whether the European B. stevensii is the same species as B. phalloides.

Handkea utriformis, synonymous with Lycoperdon utriforme, Lycoperdon caelatum or Calvatia utriformis, is a species of the puffball family Lycoperdaceae. A rather large mushroom, it may reach dimensions of up to 25 cm (10 in) broad by 20 cm (8 in) tall. It is commonly known as the mosaic puffball, a reference to the polygonal-shaped segments the outer surface of the fruiting body develops as it matures. Widespread in northern temperate zones, it is found frequently on pastures and sandy heaths, and is edible when young. H. utriformis has antibiotic activity against a number of bacteria, and can bioaccumulate the trace metals copper and zinc to relatively high concentrations.

Astraeus hygrometricus, commonly known as the hygroscopic earthstar, the barometer earthstar, or the false earthstar, is a species of fungus in the family Diplocystaceae. Young specimens resemble a puffball when unopened. In maturity, the mushroom displays the characteristic earthstar shape that is a result of the outer layer of fruit body tissue splitting open in a star-like manner. The false earthstar is an ectomycorrhizal species that grows in association with various trees, especially in sandy soils. A. hygrometricus was previously thought to have a cosmopolitan distribution, though it is now thought to be restricted to Southern Europe, and Astraeus are common in temperate and tropical regions. Its common names refer to the fact that it is hygroscopic (water-absorbing) and can open up its rays to expose the spore sac in response to increased humidity, then close them up again in drier conditions. The rays have an irregularly cracked surface, while the spore case is pale brown and smooth with an irregular slit or tear at the top. The gleba is white initially, but turns brown and powdery when the spores mature. The spores are reddish-brown and roughly spherical with minute warts, measuring 7.5–11 micrometers in diameter.

Astraeus is a genus of fungi in the family Diplocystaceae. The genus, which has a cosmopolitan distribution, contains nine species of earthstar mushroom. They are distinguished by the outer layer of flesh (exoperidium) that at maturity splits open in a star-shape manner to reveal a round spore sac. Additionally, they have a strongly hygroscopic character—the rays will open when moist, but when hot and dry will close to protect the spore sac. Species of Astraeus grow on the ground in ectomycorrhizal associations with trees and shrubs. Despite their similar appearance to the Geastrum earthstars, the species of Astraeus are not closely related.

Geastrum triplex is a fungus found in the detritus and leaf litter of hardwood forests around the world. It is commonly known as the collared earthstar, the saucered earthstar, or the triple earthstar—and less commonly by the alternative species name Geastrum indicum. It is the largest member of the genus Geastrum and expanded mature specimens can reach a tip-to-tip length of up to 12 centimeters.

Limnoperdon is a fungal genus in the monotypic family Limnoperdaceae. The genus is also monotypic, as it contains a single species, the aquatic fungus Limnoperdon incarnatum. The species, described as new to science in 1976, produces fruit bodies that lack specialized structures such as a stem, cap and gills common in mushrooms. Rather, the fruit bodies—described as aquatic or floating puffballs—are small balls of loosely interwoven hyphae. The balls float on the surface of the water above submerged twigs. Experimental observations on the development of the fruit body, based on the growth on the fungus in pure culture, suggest that a thin strand of mycelium tethers the ball above water while it matures. Fruit bodies start out as a tuft of hyphae, then become cup-shaped, and eventually enclose around a single chamber that contains reddish spores. Initially discovered in a marsh in the state of Washington, the fungus has since been collected in Japan, South Africa, and Canada.

Lycoperdon echinatum, commonly known as the spiny puffball or the spring puffball, is a type of puffball mushroom in the family Agaricaceae. The saprobic species has been found in Africa, Europe, Central America, and North America, where it grows on soil in deciduous woods, glades, and pastures. It has been proposed that North American specimens be considered a separate species, Lycoperdon americanum, but this suggestion has not been followed by most authors. Molecular analysis indicates that L. echinatum is closely related to the puffball genus Handkea.

The gasteroid fungi are a group of fungi in the Basidiomycota. Species were formerly placed in the obsolete class Gasteromycetes Fr., or the equally obsolete order Gasteromycetales Rea, because they produce spores inside their basidiocarps rather than on an outer surface. However, the class is polyphyletic, as such species—which include puffballs, earthballs, earthstars, stinkhorns, bird's nest fungi, and false truffles—are not closely related to each other. Because they are often studied as a group, it has been convenient to retain the informal (non-taxonomic) name of "gasteroid fungi".

Geastrum quadrifidum, commonly known as the rayed earthstar or four-footed earthstar, is an inedible species of mushroom belonging to the genus Geastrum, or earthstar fungi. First described scientifically by Christian Hendrik Persoon in 1794, G. quadrifidum is a cosmopolitan—but not common—species of Europe, the Americas, Africa, Asia, and Australasia. The fungus is a saprobe, feeding off decomposing organic matter present in the soil and litter of coniferous forests.

Calostoma cinnabarinum, commonly known as the stalked puffball-in-aspic,gelatinous stalked-puffball, or red slimy-stalked puffball, is a species of gasteroid fungus in the family Sclerodermataceae, and is the type species of the genus Calostoma. The fruit body has a distinctive color and overall appearance, featuring a layer of yellowish jelly surrounding a bright red, spherical head approximately 2 centimeters (0.8 in) in diameter atop a red or yellowish brown spongy stipe 1.5 to 4 cm tall. The innermost layer of the head is the gleba, containing clear or slightly yellowish elliptical spores, measuring 14–20 micrometers (μm) long by 6–9 μm across. The spore surface features a pattern of small pits, producing a net-like appearance. A widely distributed species, it grows naturally in eastern North America, Central America, northeastern South America, and East Asia. C. cinnabarinum grows on the ground in deciduous forests, where it forms mycorrhizal associations with oaks.

Sclerodermatineae is a suborder of the fungal order Boletales. Circumscribed in 2002 by mycologists Manfred Binder and Andreas Bresinsky, it contains nine genera and about 80 species. The suborder contains a diverse assemblage fruit body morphologies, including boletes, gasteroid forms, earthstars, and puffballs. Most species are ectomycorrhizal, although the ecological role of some species is not known with certainty. The suborder is thought to have originated in the late Cretaceous (145–66 Ma) in Asia and North America, and the major genera diversified around the mid Cenozoic (66–0 Ma).