The Amarna letters are an archive, written on clay tablets, primarily consisting of diplomatic correspondence between the Egyptian administration and its representatives in Canaan and Amurru, or neighboring kingdom leaders, during the New Kingdom, spanning a period of no more than thirty years in the middle 14th century BC. The letters were found in Upper Egypt at el-Amarna, the modern name for the ancient Egyptian capital of Akhetaten, founded by pharaoh Akhenaten during the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt.

The Beqaa Valley is a fertile valley in eastern Lebanon and its most important farming region. Industry, especially the country's agricultural industry, also flourishes in Beqaa. The region broadly corresponds to the Coele-Syria of classical antiquity.

The Baalberge Group was a late neolithic "culture" in Central Germany and Bohemia between 4000 and 3150 BC. Because of issues with the archaeological use of the term culture it is now often referred to as the Baalberge Ceramic style. It is named after its first findspot: on the Schneiderberg at Baalberge, Salzlandkreis, Saxony-Anhalt. The Baalberge group is generally seen as part of the Funnelbeaker culture. In the Middle Elbe/Saale region it is part of Funnelbeaker phase TRB-MES II and III.

Argissa Magoula is a Neolithic settlement mound (tell) in Thessaly in Greece. It was excavated by Vladimir Milojčić from the University of Heidelberg in the 1950s. He claimed to have found evidence of an aceramic Neolithic, but this has been disputed.

The Wartberg culture, sometimes: Wartberg group (Wartberggruppe) or Collared bottle culture (Kragenflaschenkultur) is a prehistoric culture from 3,600 -2,800 BC of the later Central European Neolithic. It is named after its type site, the Wartberg, a hill near Niedenstein-Kirchberg in northern Hesse, Germany.

Hans-Georg Stephan is a German university professor specializing in European medieval archaeology and post-medieval archaeology.

Joachim Werner was a German archaeologist who was especially concerned with the archaeology of the Early Middle Ages in Germany. The majority of German professorships with particular focus on the field of the Early Middle Ages were in the second half of the 20th century occupied by his academic pupils.

Tell Jisr, Tell el-Jisr or Tell ej-Jisr is a hill and archaeological site 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) northwest of Joub Jannine in the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon.

Aammiq is a village in the Western Beqaa District in Lebanon. It is also the name of an archaeological site.

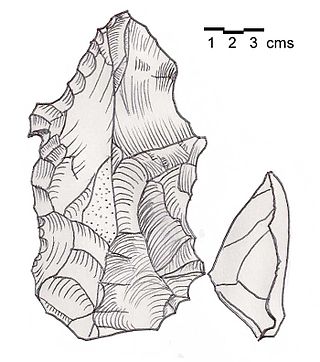

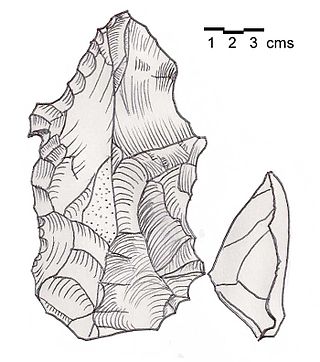

Heavy Neolithic is a style of large stone and flint tools associated primarily with the Qaraoun culture in the Beqaa Valley, Lebanon, dating to the Epipaleolithic or early Pre-Pottery Neolithic at the end of the Stone Age. The type site for the Qaraoun culture is Qaraoun II.

Herbert Rüdiger Ricke, was a German archaeologist, Egyptologist and architectural historian who is best known for his works on ancient Egyptian architecture.

The various types of megalithic monuments in northeastern Germany were last compiled by Ewald Schuldt in the course of a project to excavate megalithic tombs from the Neolithic Era, which was conducted between 1964 and 1972 in the area of the northern districts of East Germany. His aim was to provide a "classification and naming of the objects present in this field of research". In doing so it utilised a classification by Ernst Sprockhoff, which in turn was based on an older Danish model.

Tell Aalaq is an archaeological site 9 km west of Baalbek in the Beqaa Mohafazat (Governorate). It dates at least to the early Bronze Age.

Rolf Hachmann was a German archaeologist who specialized in pre- and protohistory.

Horst Wolfgang Böhme is a German archaeologist with a focus on Late Antiquity / Early Middle Ages and research into castles.

Raiko Krauss, born 1973 in Friedrichshain, Berlin is a German archaeologist of prehistory.

Jürgen Oldenstein is a German provincial Roman archaeologist.

Sebastian Brather is a German medieval archaeologist and co-editor of Germanische Altertumskunde Online.

Andreas Zimmermann, is a German archaeologist. His scholarly focus is the Neolithic, in particular the LBK. Zimmermann studied geology, archaeology, and Egyptology at universities in Cologne and Tübingen. His 1982 dissertation was on the lithic material from the LBK site Langweiler 8. In 1992, he produced his habilitation from Frankfurt University, on the exchange of flint artifacts in central Europe during the Neolithic. Until becoming an emeritus in 2016, he was a professor at the Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte at Cologne University starting in 1997.