Related Research Articles

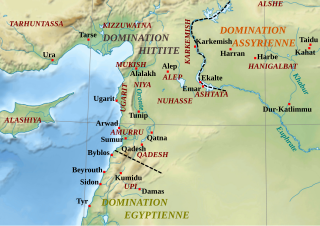

The Hittites were an Anatolian Indo-European people who formed one of the first major civilizations of Bronze Age West Asia. Possibly originating from beyond the Black Sea, they settled in modern-day Turkey in the early 2nd millennium BC. The Hittites formed a series of polities in north-central Anatolia, including the kingdom of Kussara, the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom, and an empire centered on Hattusa. Known in modern times as the Hittite Empire, it reached its peak during the mid-14th century BC under Šuppiluliuma I, when it encompassed most of Anatolia and parts of the northern Levant and Upper Mesopotamia, bordering the rival empires of the Hurri-Mitanni and Assyrians.

The Hurrians were a people who inhabited the Ancient Near East during the Bronze Age. They spoke the Hurrian language, and lived throughout northern Syria, upper Mesopotamia and southeastern Anatolia.

Mitanni, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat in Assyrian records, or Naharin in Egyptian texts, was a Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria and southeast Anatolia with Indo-Aryan linguistic and political influences. Since no histories, royal annals or chronicles have yet been found in its excavated sites, knowledge about Mitanni is sparse compared to the other powers in the area, and dependent on what its neighbours commented in their texts.

Yamhad (Yamḫad) was an ancient Semitic-speaking kingdom centered on Ḥalab (Aleppo) in Syria. The kingdom emerged at the end of the 19th century BC and was ruled by the Yamhad dynasty, who counted on both military and diplomacy to expand their realm. From the beginning of its establishment, the kingdom withstood the aggressions of its neighbors Mari, Qatna and the Old Assyrian Empire, and was turned into the most powerful Syrian kingdom of its era through the actions of its king Yarim-Lim I. By the middle of the 18th century BC, most of Syria minus the south came under the authority of Yamhad, either as a direct possession or through vassalage, and for nearly a century and a half, Yamhad dominated northern, northwestern and eastern Syria, and had influence over small kingdoms in Mesopotamia at the borders of Elam. The kingdom was eventually destroyed by the Hittites, then annexed by Mitanni in the 16th century BC.

Carchemish, also spelled Karkemish, was an important ancient capital in the northern part of the region of Syria. At times during its history the city was independent, but it was also part of the Mitanni, Hittite and Neo-Assyrian Empires. Today it is on the frontier between Turkey and Syria.

Shamshi-Adad, ruled c. 1808–1776 BC, was an Amorite warlord and conqueror who had conquered lands across much of Syria, Anatolia, and Upper Mesopotamia. His capital was originally at Ekallatum and later moved to Šubat-Enlil.

Isuwa, was a kingdom founded by the Hurrians, which came under Hittite sovereignty towards 1600 BC as a result of their struggle with the Hittites.

Nuhašše, was a region in northwestern Syria that flourished in the 2nd millennium BC. It was east of the Orontes River bordering Aleppo (northwest) and Qatna (south). It was a petty kingdom or federacy of principalities probably under a high king. Tell Khan Sheykhun has tenatively been identified as kurnu-ḫa-šeki.

The Old Assyrian period was the second stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of the city of Assur from its rise as an independent city-state under Puzur-Ashur I c. 2025 BC to the foundation of a larger Assyrian territorial state after the accession of Ashur-uballit I c. 1363 BC, which marks the beginning of the succeeding Middle Assyrian period. The Old Assyrian period is marked by the earliest known evidence of the development of a distinct Assyrian culture, separate from that of southern Mesopotamia and was a geopolitically turbulent time when Assur several times fell under the control or suzerainty of foreign kingdoms and empires. The period is also marked with the emergence of a distinct Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language, a native Assyrian calendar and Assur for a time becoming a prominent site for international trade.

The Battle of Niḫriya was the culminating point of the hostilities between the Hittites and the Assyrians for control over the remnants of the former empire of Mitanni in Upper Mesopotamia, in the second half of the 13th Century BC.

Shamshi-ilu (Šamši-ilu) was an influential court dignitary and commander in chief (turtanu) of the Assyrian army who rose in high prominence.

Aplahanda was a king of Carchemish proposed to have reigned between 1786 and 1766 BCE, during the Middle Bronze IIA.

Yarim-Lim I, also given as Yarimlim, was the second king of the ancient Amorite kingdom of Yamhad in modern-day Aleppo, Syria.

Sumu-Epuh is the first attested king of Yamhad (Halab). He founded the Yamhad dynasty which controlled northern Syria throughout the 17th and 18th centuries BC.

Irridu (Irrite) was a city in northwestern Mesopotamia, likely located between Harran and Carchemish. It flourished in the middle and late Bronze Age before being destroyed by Assyria.

Yarim-Lim III was the king of Yamhad (Halab) succeeding Hammurabi II.

Hassum was a Hurrian city-state, located in southern Turkey most probably on the Euphrates river north of Carchemish.

The Yamhad dynasty was an ancient Amorite royal family founded in c. 1810 BC by Sumu-Epuh of Yamhad who had his capital in the city of Aleppo. Started as a local dynasty, the family expanded its influence through the actions of its energetic ruler Yarim-Lim I who turned it into the most influential family in the Levant through both diplomatic and military tools. At its height the dynasty controlled most of northern Syria and the modern Turkish province of Hatay with a cadet branch ruling in the city of Alalakh.

Lawazantiya was a major Bronze Age city in the Kingdom of Kizzuwatna and the cultic city of the goddess Šauška. It was famous for its temple that got purification water from its seven springs. Today the best candidate for the site is Tatarli Höyük which is known for its seven springs.

The timeline of ancient Assyria can be broken down into three main eras: the Old Assyrian period, Middle Assyrian Empire, and Neo-Assyrian Empire. Modern scholars typically also recognize an Early period preceding the Old Assyrian period and a post-imperial period succeeding the Neo-Assyrian period.

References

Citations

- ↑ I. M. Diakonoff (28 June 2013). Early Antiquity. p. 364. ISBN 9780226144672.

- ↑ Noel Freedman; Allen C. Myers (31 December 2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. p. 619. ISBN 9789053565032.

- ↑ Mogens Herman Hansen (2000). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation, Volume 21. p. 60. ISBN 9788778761774.

- 1 2 Sidney Smith (1956). Anatolian Studies: Journal of the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara. Special number in honour and in memory of John Garstang, 5th May, 1876 - 12th September, 1956, Volume 6. p. 42.

- ↑ I. E. S. Edwards; C. J. Gadd; N. G. L. Hammond; E. Sollberger (3 May 1973). The Cambridge Ancient History. p. 241. ISBN 9780521082303.

- ↑ Gojko Barjamovic (2011). A Historical Geography of Anatolia in the Old Assyrian Colony Period. p. 200+201. ISBN 9788763536455.

- ↑ Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards; C. J. Gadd; N. G. L. Hammond (31 October 1971). The Cambridge Ancient History. p. 559. ISBN 9780521077910.

- ↑ Gwendolyn Leick (2 June 2009). The Babylonian World. p. 537. ISBN 9781134261284.

- ↑ Archi, Alfonso (2011). "In Search of Armi". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 63. The American Schools of Oriental Research: 5–34. doi:10.5615/jcunestud.63.0005. ISSN 2325-6737. S2CID 163552750. p.29

- ↑ Yuhong Wu (1994). A Political History of Eshnunna, Mari and Assyria During the Early Old Babylonian Period: From the End of Ur III to the Death of Šamši-Adad. p. 131.

- ↑ Sidney Smith (1956). Anatolian Studies: Journal of the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara. Special number in honour and in memory of John Garstang, 5th May, 1876 - 12th September, 1956, Volume 6. p. 39.

- 1 2 Gojko Barjamovic (2011). A Historical Geography of Anatolia in the Old Assyrian Colony Period. p. 202. ISBN 9788763536455.

- ↑ Beatrice Teissier (1996). Egyptian Iconography on Syro-Palestinian Cylinder Seals of the Middle Bronze Age. p. 1. ISBN 9783525538920.

- ↑ J. R. Kupper. The Cambridge Ancient History Northern Mesopotamia and Syria. p. 19.

- ↑ William J. Hamblin (27 September 2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. p. 255. ISBN 9781134520626.

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (March 2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 27. ISBN 9780199646678.

- ↑ Horst Klengel (20 March 1992). Syria, 3000 to 300 B.C.: a handbook of political history. p. 75. ISBN 9783050018201.

- ↑ Seton Lloyd (21 August 2007). Hittite Warrior. p. 44. ISBN 9781846030819.

- ↑ Robert Drews (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C. p. 106. ISBN 0691025916.

- ↑ I. E. S. Edwards; C. J. Gadd; N. G. L. Hammond; E. Sollberger (3 May 1973). The Cambridge Ancient History. p. 245. ISBN 9780521082303.

- ↑ Seton Lloyd (1999). Ancient Turkey: A Traveller's History. p. 39. ISBN 9780520220423.

- 1 2 Gojko Barjamovic (2011). A Historical Geography of Anatolia in the Old Assyrian Colony Period. p. 203. ISBN 9788763536455.