Iron(III) chloride describes the inorganic compounds with the formula FeCl3(H2O)x. Also called ferric chloride, these compounds are some of the most important and commonplace compounds of iron. They are available both in anhydrous and in hydrated forms, which are both hygroscopic. They feature iron in its +3 oxidation state. The anhydrous derivative is a Lewis acid, while all forms are mild oxidizing agents. It is used as a water cleaner and as an etchant for metals.

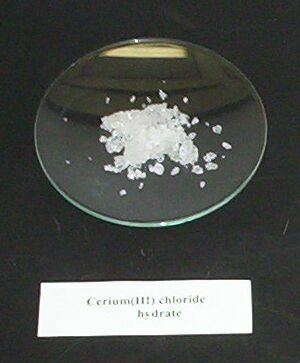

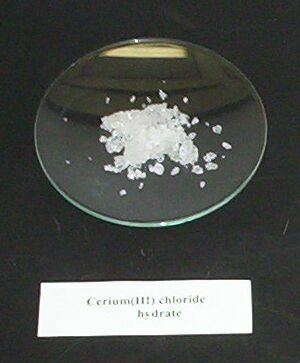

Cerium(III) chloride (CeCl3), also known as cerous chloride or cerium trichloride, is a compound of cerium and chlorine. It is a white hygroscopic salt; it rapidly absorbs water on exposure to moist air to form a hydrate, which appears to be of variable composition, though the heptahydrate CeCl3·7H2O is known. It is highly soluble in water, and (when anhydrous) it is soluble in ethanol and acetone.

The Stille reaction is a chemical reaction widely used in organic synthesis. The reaction involves the coupling of two organic groups, one of which is carried as an organotin compound (also known as organostannanes). A variety of organic electrophiles provide the other coupling partner. The Stille reaction is one of many palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions.

The Suzuki reaction or Suzuki coupling is an organic reaction that uses a palladium complex catalyst to cross-couple a boronic acid to an organohalide. It was first published in 1979 by Akira Suzuki, and he shared the 2010 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Richard F. Heck and Ei-ichi Negishi for their contribution to the discovery and development of noble metal catalysis in organic synthesis. This reaction is sometimes telescoped with the related Miyaura borylation; the combination is the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction. It is widely used to synthesize polyolefins, styrenes, and substituted biphenyls.

Iron(II) chloride, also known as ferrous chloride, is the chemical compound of formula FeCl2. It is a paramagnetic solid with a high melting point. The compound is white, but typical samples are often off-white. FeCl2 crystallizes from water as the greenish tetrahydrate, which is the form that is most commonly encountered in commerce and the laboratory. There is also a dihydrate. The compound is highly soluble in water, giving pale green solutions.

The Hiyama coupling is a palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of organosilanes with organic halides used in organic chemistry to form carbon–carbon bonds. This reaction was discovered in 1988 by Tamejiro Hiyama and Yasuo Hatanaka as a method to form carbon-carbon bonds synthetically with chemo- and regioselectivity. The Hiyama coupling has been applied to the synthesis of various natural products.

The Ullmann condensation or Ullmann-type reaction is the copper-promoted conversion of aryl halides to aryl ethers, aryl thioethers, aryl nitriles, and aryl amines. These reactions are examples of cross-coupling reactions.

The Weinreb ketone synthesis or Weinreb–Nahm ketone synthesis is a chemical reaction used in organic chemistry to make carbon–carbon bonds. It was discovered in 1981 by Steven M. Weinreb and Steven Nahm as a method to synthesize ketones. The original reaction involved two subsequent substitutions: the conversion of an acid chloride with N,O-Dimethylhydroxylamine, to form a Weinreb–Nahm amide, and subsequent treatment of this species with an organometallic reagent such as a Grignard reagent or organolithium reagent. Nahm and Weinreb also reported the synthesis of aldehydes by reduction of the amide with an excess of lithium aluminum hydride.

Tellurium tetrachloride is the inorganic compound with the empirical formula TeCl4. The compound is volatile, subliming at 200 °C at 0.1 mmHg. Molten TeCl4 is ionic, dissociating into TeCl3+ and Te2Cl102−.

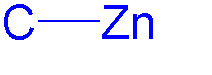

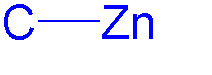

Organozinc chemistry is the study of the physical properties, synthesis, and reactions of organozinc compounds, which are organometallic compounds that contain carbon (C) to zinc (Zn) chemical bonds.

Organocopper chemistry is the study of the physical properties, reactions, and synthesis of organocopper compounds, which are organometallic compounds containing a carbon to copper chemical bond. They are reagents in organic chemistry.

In organic chemistry, the Buchwald–Hartwig amination is a chemical reaction for the synthesis of carbon–nitrogen bonds via the palladium-catalyzed coupling reactions of amines with aryl halides. Although Pd-catalyzed C–N couplings were reported as early as 1983, Stephen L. Buchwald and John F. Hartwig have been credited, whose publications between 1994 and the late 2000s established the scope of the transformation. The reaction's synthetic utility stems primarily from the shortcomings of typical methods for the synthesis of aromatic C−N bonds, with most methods suffering from limited substrate scope and functional group tolerance. The development of the Buchwald–Hartwig reaction allowed for the facile synthesis of aryl amines, replacing to an extent harsher methods while significantly expanding the repertoire of possible C−N bond formations.

Organotitanium chemistry is the science of organotitanium compounds describing their physical properties, synthesis, and reactions. Organotitanium compounds in organometallic chemistry contain carbon-titanium chemical bonds. They are reagents in organic chemistry and are involved in major industrial processes.

Organoarsenic chemistry is the chemistry of compounds containing a chemical bond between arsenic and carbon. A few organoarsenic compounds, also called "organoarsenicals," are produced industrially with uses as insecticides, herbicides, and fungicides. In general these applications are declining in step with growing concerns about their impact on the environment and human health. The parent compounds are arsane and arsenic acid. Despite their toxicity, organoarsenic biomolecules are well known.

Organoantimony chemistry is the chemistry of compounds containing a carbon to antimony (Sb) chemical bond. Relevant oxidation states are SbV and SbIII. The toxicity of antimony limits practical application in organic chemistry.

The Heck–Matsuda (HM) reaction is an organic reaction and a type of palladium catalysed arylation of olefins that uses arenediazonium salts as an alternative to aryl halides and triflates.

Organocerium chemistry is the science of organometallic compounds that contain one or more chemical bond between carbon and cerium. These compounds comprise a subset of the organolanthanides. Most organocerium compounds feature Ce(III) but some Ce(IV) derivatives are known.

The Chan–Lam coupling reaction – also known as the Chan–Evans–Lam coupling is a cross-coupling reaction between an aryl boronic acid and an alcohol or an amine to form the corresponding secondary aryl amines or aryl ethers, respectively. The Chan–Lam coupling is catalyzed by copper complexes. It can be conducted in air at room temperature. The more popular Buchwald–Hartwig coupling relies on the use of palladium.

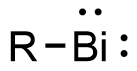

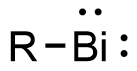

Bismuthinidenes are a class of organobismuth compounds, analogous to carbenes. These compounds have the general form R-Bi, with two lone pairs of electrons on the central bismuth(I) atom. Due to the unusually low valency and oxidation state of +1, most bismuthinidenes are reactive and unstable, though in recent decades, both transition metals and polydentate chelating Lewis base ligands have been employed to stabilize the low-valent bismuth(I) center through steric protection and π donation either in solution or in crystal structures. Lewis base-stabilized bismuthinidenes adopt a singlet ground state with an inert lone pair of electrons in the 6s orbital. A second lone pair in a 6p orbital and a single empty 6p orbital make Lewis base-stabilized bismuthinidenes ambiphilic. Recently, a triplet bismuthinidene is reported by Cornella et al.

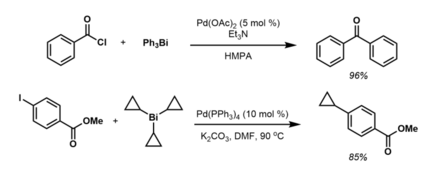

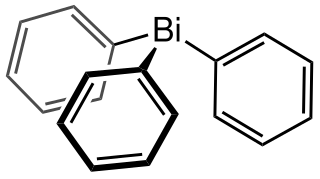

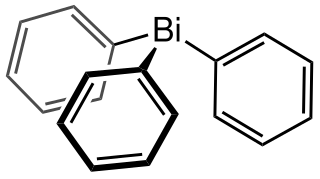

Triphenylbismuthine is an organobismuth compound with the formula Bi(C6H5)3. It is a white, air-stable solid that is soluble in organic solvents. It is prepared by treatment of bismuth trichloride with phenylmagnesium bromide.