Human geography or anthropogeography is the branch of geography which studies spatial relationships between human communities, cultures, economies, and their interactions with the environment, examples of which include urban sprawl and urban redevelopment. It analyzes spatial interdependencies between social interactions and the environment through qualitative and quantitative methods. This multidisciplinary approach draws from sociology, anthropology, economics, and environmental science, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the intricate connections that shape lived spaces.

Physical geography is one of the three main branches of geography. Physical geography is the branch of natural science which deals with the processes and patterns in the natural environment such as the atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and geosphere. This focus is in contrast with the branch of human geography, which focuses on the built environment, and technical geography, which focuses on using, studying, and creating tools to obtain, analyze, interpret, and understand spatial information. The three branches have significant overlap, however.

Environmental determinism is the study of how the physical environment predisposes societies and states towards particular economic or social developmental trajectories. Jared Diamond, Jeffrey Herbst, Ian Morris, and other social scientists sparked a revival of the theory during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. This "neo-environmental determinism" school of thought examines how geographic and ecological forces influence state-building, economic development, and institutions. While archaic versions of the geographic interpretation were used to encourage colonialism and eurocentrism, modern figures like Diamond use this approach to reject the racism in these explanations. Diamond argues that European powers were able to colonize, due to unique advantages bestowed by their environment, as opposed to any kind of inherent superiority.

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" and the Greek suffix, "graphy", meaning "description", so a geographer is someone who studies the earth. The word "geography" is a Middle French word that is believed to have been first used in 1540.

Geopolitics is the study of the effects of Earth's geography on politics and international relations. Geopolitics usually refers to countries and relations between them, it may also focus on two other kinds of states: de facto independent states with limited international recognition and relations between sub-national geopolitical entities, such as the federated states that make up a federation, confederation, or a quasi-federal system.

Karl Ernst Haushofer was a German general, professor, geographer, and diplomat. Haushofer's concept of Geopolitik influenced the ideological development of Adolf Hitler. Rudolf Hess was also a student of Haushofer, and during Hess and Hitler's incarceration by the Weimar Republic after the Beer Hall Putsch, Haushofer visited Landsberg Prison to teach and mentor both Hess and Hitler. Haushofer also coined the political use of the term Lebensraum, which Hitler also used to justify both crimes against peace and genocide. At the same time, however, Gen. Haushofer's half-Jewish wife and their children were categorized as Mischlinge under the Nuremberg Laws. Their son, Albrecht Haushofer, was issued a German Blood Certificate through the influence of Rudolf Hess, but was arrested in 1944 over his involvement with the July 20th plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler and overthrow the Nazi Party. During the last days of the war, Albrecht Haushofer was summarily executed by the SS for his role in the German Resistance.

Economic geography is the subfield of human geography that studies economic activity and factors affecting it. It can also be considered a subfield or method in economics.

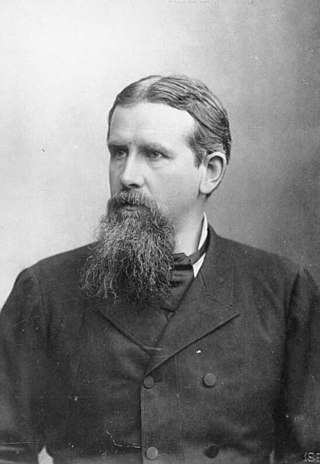

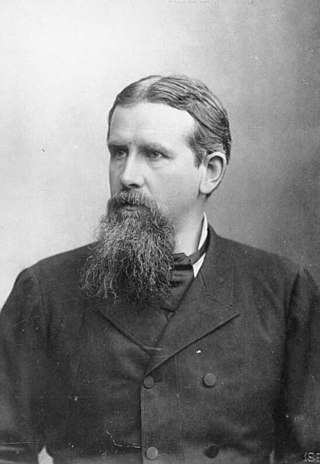

Sir Halford John Mackinder was a British geographer, academic and politician, who is regarded as one of the founding fathers of both geopolitics and geostrategy. He was the first Principal of University Extension College, Reading from 1892 to 1903, and Director of the London School of Economics from 1903 to 1908. While continuing his academic career part-time, he was also the Conservative and Unionist Member of Parliament for Glasgow Camlachie from 1910 to 1922. From 1923, he was Professor of Geography at the London School of Economics.

Feminist geography is a sub-discipline of human geography that applies the theories, methods, and critiques of feminism to the study of the human environment, society, and geographical space. Feminist geography emerged in the 1970s, when members of the women's movement called on academia to include women as both producers and subjects of academic work. Feminist geographers aim to incorporate positions of race, class, ability, and sexuality into the study of geography. The discipline was a target for the hoaxes of the grievance studies affair.

Friedrich Ratzel was a German geographer and ethnographer, notable for first using the term Lebensraum in the sense that the National Socialists later would.

Geostrategy, a subfield of geopolitics, is a type of foreign policy guided principally by geographical factors as they inform, constrain, or affect political and military planning. As with all strategies, geostrategy is concerned with matching means to ends Strategy is as intertwined with geography as geography is with nationhood, or as Colin S. Gray and Geoffrey Sloan state it, "[geography is] the mother of strategy."

Johan Rudolf Kjellén was a Swedish political scientist, geographer and politician who first coined the term "geopolitics". His work was influenced by Friedrich Ratzel. Along with Alexander von Humboldt, Carl Ritter, and Ratzel, Kjellén would lay the foundations for the German Geopolitik that would later be espoused prominently by General Karl Haushofer.

Geopolitik was a German school of geopolitics which existed between the late 19th century and World War II.

Ellen Churchill Semple was an American geographer and the first female president of the Association of American Geographers. She contributed significantly to the early development of the discipline of geography in the United States, particularly studies of human geography. She is most closely associated with work in anthropogeography and environmentalism, and the debate about "environmental determinism".

Cultural geography is a subfield within human geography. Though the first traces of the study of different nations and cultures on Earth can be dated back to ancient geographers such as Ptolemy or Strabo, cultural geography as academic study firstly emerged as an alternative to the environmental determinist theories of the early 20th century, which had believed that people and societies are controlled by the environment in which they develop. Rather than studying predetermined regions based upon environmental classifications, cultural geography became interested in cultural landscapes. This was led by the "father of cultural geography" Carl O. Sauer of the University of California, Berkeley. As a result, cultural geography was long dominated by American writers.

"The Geographical Pivot of History" is an article submitted by Halford John Mackinder in 1904 to the Royal Geographical Society that advances his heartland theory. In this article, Mackinder extended the scope of geopolitical analysis to encompass the entire globe. He defined Afro-Eurasia as the "world island" and its "heartland" as the area east of the Volga, south of the Arctic, west of the Yangtze, and north of the Himalayas. Due to its strategic location and natural resources, Mackinder argued that whoever controlled the "heartland" could control the world.

Critical geography is theoretically informed geographical scholarship that promotes social justice, liberation, and leftist politics. Critical geography is also used as an umbrella term for Marxist, feminist, postmodern, poststructural, queer, left-wing, and activist geography.

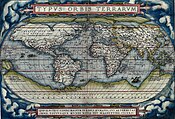

Geography is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding of Earth and its human and natural complexities—not merely where objects are, but also how they have changed and come to be. While geography is specific to Earth, many concepts can be applied more broadly to other celestial bodies in the field of planetary science. Geography has been called "a bridge between natural science and social science disciplines."

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to geography: