Positive affectivity has also been linked to improvements in cognitive processing in early development. Research in developmental psychology shows that children experiencing higher levels of positive emotion tend to engage in more systematic and explanation-based reasoning. For example, Bailey, Williams, and Cimpian (2022) found that positive affect was associated with a greater tendency to seek coherent, rule-based explanations when learning from examples, suggesting that positive emotional states may support deeper conceptual processing in childhood. [9]

Effects

Overall, positive affect results in a more positive outlook, increases problem solving skills, increases social skills, increases activity and projects, and can play a role in motor function. [1] [10]

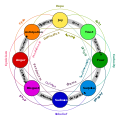

Positive affectivity is an integral part of everyday life. [11] PA helps individuals to process emotional information accurately and efficiently, to solve problems, to make plans, and to earn achievements. The broaden-and-build theory of PA [12] [13] suggests that PA broadens people's momentary thought-action repertoires and builds their enduring personal resources.

Research shows that PA relates to different classes of variables, such as social activity and the frequency of pleasant events. [7] [14] [15] [16] PA also strongly relates to life satisfaction. [17] The high energy and engagement, optimism, and social interest characteristic of high-PA individuals suggest that they are more likely to be satisfied with their lives. [7] [8] In fact, the content similarities between these affective traits and life satisfaction have led some researchers to view both PA, NA, and life satisfaction as specific indicators of the broader construct of subjective well-being. [18] [11]

PA may influence the relationships between variables in organizational research. [19] [20] PA increases attentional focus and behavioral repertoire, and these enhanced personal resources can help to overcome or deal with distressing situations. These resources are physical (e.g., better health), social (e.g., social support networks), and intellectual and psychological (e.g., resilience, optimism, and creativity).

PA provides a psychological break or respite from stress, [2] supporting continued efforts to replenish resources depleted by stress. [21] [22] Its buffering functions provide a useful antidote to the problems associated with negative emotions and ill health due to stress, [13] as PA reduces allostatic load. [2] Likewise, happy people are better at coping. McCrae and Costa [23] concluded that PA was associated with more mature coping efforts.