Related Research Articles

Remorse is a distressing emotion experienced by an individual who regrets actions which they have done in the past that they deem to be shameful, hurtful, or wrong. Remorse is closely allied to guilt and self-directed resentment. When a person regrets an earlier action or failure to act, it may be because of remorse or in response to various other consequences, including being punished for the act or omission. People may express remorse through apologies, trying to repair the damage they've caused, or self-imposed punishments.

Empathy is generally described as the ability to take on another person's perspective, to understand, feel, and possibly share and respond to their experience. There are more definitions of empathy that include but are not limited to social, cognitive, and emotional processes primarily concerned with understanding others. Often times, empathy is considered to be a broad term, and broken down into more specific concepts and types that include cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, somatic empathy, and spiritual empathy.

Sympathy is the perception of, understanding of, and reaction to the distress or need of another life form.

A mirror neuron is a neuron that fires both when an animal acts and when the animal observes the same action performed by another. Thus, the neuron "mirrors" the behavior of the other, as though the observer were itself acting. Mirror neurons are not always physiologically distinct from other types of neurons in the brain; their main differentiating factor is their response patterns. By this definition, such neurons have been directly observed in humans and other primates, and in birds.

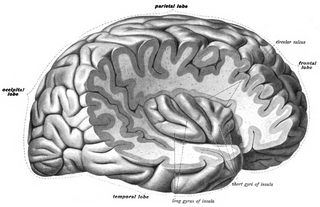

The insular cortex is a portion of the cerebral cortex folded deep within the lateral sulcus within each hemisphere of the mammalian brain.

Affective neuroscience is the study of how the brain processes emotions. This field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The basis of emotions and what emotions are remains an issue of debate within the field of affective neuroscience.

The simulation theory of empathy holds that humans anticipate and make sense of the behavior of others by activating mental processes that, if they culminated in action, would produce similar behavior. This includes intentional behavior as well as the expression of emotions. The theory says that children use their own emotions to predict what others will do; we project our own mental states onto others.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is a part of the prefrontal cortex in the mammalian brain. The ventral medial prefrontal is located in the frontal lobe at the bottom of the cerebral hemispheres and is implicated in the processing of risk and fear, as it is critical in the regulation of amygdala activity in humans. It also plays a role in the inhibition of emotional responses, and in the process of decision-making and self-control. It is also involved in the cognitive evaluation of morality.

The self-regulation of emotion or emotion regulation is the ability to respond to the ongoing demands of experience with the range of emotions in a manner that is socially tolerable and sufficiently flexible to permit spontaneous reactions as well as the ability to delay spontaneous reactions as needed. It can also be defined as extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions. The self-regulation of emotion belongs to the broader set of emotion regulation processes, which includes both the regulation of one's own feelings and the regulation of other people's feelings.

Empathic concern refers to other-oriented emotions elicited by, and congruent with the perceived welfare of, someone in need. These other-oriented emotions include feelings of tenderness, sympathy, compassion and soft-heartedness.

Disgust is an emotional response of rejection or revulsion to something potentially contagious or something considered offensive, distasteful or unpleasant. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin wrote that disgust is a sensation that refers to something revolting. Disgust is experienced primarily in relation to the sense of taste, and secondarily to anything which causes a similar feeling by sense of smell, touch, or vision. Musically sensitive people may even be disgusted by the cacophony of inharmonious sounds. Research has continually proven a relationship between disgust and anxiety disorders such as arachnophobia, blood-injection-injury type phobias, and contamination fear related obsessive–compulsive disorder.

In psychology, empathic accuracy is a measure of how accurately one person can infer the thoughts and feelings of another person.

Cultural neuroscience is a field of research that focuses on the interrelation between a human's cultural environment and neurobiological systems. The field particularly incorporates ideas and perspectives from related domains like anthropology, psychology, and cognitive neuroscience to study sociocultural influences on human behaviors. Such impacts on behavior are often measured using various neuroimaging methods, through which cross-cultural variability in neural activity can be examined.

A number of studies have found that human biology can be linked with political orientation. This means that an individual's biology may predispose them to a particular political orientation and ideology or, conversely, that subscription to certain ideologies may predispose them to measurable biological and health outcomes.

Pain empathy is a specific variety of empathy that involves recognizing and understanding another person's pain.

Neuromorality is an emerging field of neuroscience that studies the connection between morality and neuronal function. Scientists use fMRI and psychological assessment together to investigate the neural basis of moral cognition and behavior. Evidence shows that the central hub of morality is the prefrontal cortex guiding activity to other nodes of the neuromoral network. A spectrum of functional characteristics within this network to give rise to both altruistic and psychopathological behavior. Evidence from the investigation of neuromorality has applications in both clinical neuropsychiatry and forensic neuropsychiatry.

The dual systems model, also known as the maturational imbalance model, is a theory arising from developmental cognitive neuroscience which posits that increased risk-taking during adolescence is a result of a combination of heightened reward sensitivity and immature impulse control. In other words, the appreciation for the benefits arising from the success of an endeavor is heightened, but the appreciation of the risks of failure lags behind.

Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.

An empathy gap, sometimes referred to as an empathy bias, is a breakdown or reduction in empathy where it might otherwise be expected to occur. Empathy gaps may occur due to a failure in the process of empathizing or as a consequence of stable personality characteristics, and may reflect either a lack of ability or motivation to empathize.

Consoling touch is a pro-social behavior involving physical contact between a distressed individual and a caregiver. The physical contact, most commonly recognized in the form of a hand hold or embrace, is intended to comfort one or more of the participating individuals. Consoling touch is intended to provide consolation - to alleviate or lessen emotional or physical pain. This type of social support has been observed across species and cultures. Studies have found little difference in the applications of consoling touch, with minor differences in frequency occurrence across cultures. These findings suggest a degree of universality. It remains unclear whether the relationship between social touch and interpersonal emotional bonds reflect biologically driven or culturally normative behavior. Evidence of consoling touch in non-human primates, who embrace one another following distressing events, suggest a biological basis. Numerous studies of consoling touch in humans and animals unveil a consistent physiological response. An embrace from a friend, relative, or even stranger can trigger the release of oxytocin, dopamine, and serotonin into the bloodstream. These neurotransmitters are associated with positive mood, numerous health benefits, and longevity. Cortisol, a stress hormone, also decreases. Studies have found that the degree of intimacy and quality of relationship between consoler and the consoled mediates physiological effects. In other words, while subjects experience reduced cortisol levels while holding the hand of a stranger, they exhibit a larger effect when receiving comfort from a trusted friend, and greater still, when holding the hand of a high quality romantic partner.

References

- ↑ Shlomo Hareli; Brian Parkinson. "What's Social About Social Emotions?" (PDF). research.haifa.ac.il. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- ↑ Stephanie Bernett; Geoffrey Bird; Jorge Moll; Chris Frith; Sarah-Jayne Blakemore (September 2009). "Development during Adolescence of the Neural Processing of Social Emotion". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 21 (9): 1736–50. doi:10.1162/jocn.2009.21121. PMC 4541723 . PMID 18823226.

- ↑ Lewis, Michael. Shame: the exposed self. New York: Free Press;, 1992. 19. Print.

- ↑ Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The Growth of Logical Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence. New York, USA: Basic Books.

- ↑ Wainryb, C.; Shaw, L. A.; Maianu, C. (1998). "Tolerance and intolerance: Children's and adolescents' judgments of dissenting beliefs, speech, persons, and conduct". Child Development. 69 (6): 1541–1555. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06176.x. PMID 9914639.

- ↑ Zahn-Waxler C, Robinson J. 1995. Empathy and guilt: early origins of feelings of responsibility. In Self-Conscious Emotions ed. JP Tangney, KW Fischer, pp. 143–73. New York: Guilford

- ↑ Stipek, Deborah J; J. Heidi Gralinski; Claire B. Kopp (Nov 1990). "Self-concept development in the toddler years". Developmental Psychology. 26 (6): 972–977. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.26.6.972.

- 1 2 Harris, P.L; Olthof, K.; Terwogt, M. M.; Hardman, C. C. (September 1987). "Children's Knowledge of the Situations that Provoke Emotion". International Journal of Behavioral Development. 3. 10 (3): 319–343. doi:10.1177/016502548701000304. S2CID 145712295.

- ↑ Cwir, D.; Carr, P. B.; Walton, G. M.; Spencer, S. J. (2011). "Your heart makes my heart move: Cues of social connectedness cause shared emotions and physiological states among strangers". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 47 (3): 661–664. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.01.009.

- 1 2 3 Eisenberg, Nancy (February 2000). "Emotions, Regulations and Moral Development". Annual Review of Psychology. 51 (1): 665–697. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.665. PMID 10751984. S2CID 12168695.

- 1 2 Sanfey, A. G.; James K. Rilling1; Jessica A. Aronson; Leigh E. Nystrom1; Jonathan D. Cohen (13 June 2003). "The Neural Basis of Economic Decision-Making in the Ultimatum Game". Science. 300 (5626): 1755–1758. Bibcode:2003Sci...300.1755S. doi:10.1126/science.1082976. PMID 12805551. S2CID 7111382.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Zeman, J.; Cassano, M.; Perry-Parrish, C.; Stegall, S. (2006). "Emotion regulation in children and adolescents". Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 27 (2): 155–168. doi:10.1097/00004703-200604000-00014. PMID 16682883. S2CID 8662305.

- ↑ Elkind, David; Bowen, Robert (1 January 1979). "Imaginary audience behavior in children and adolescents". Developmental Psychology. 15 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.15.1.38.

- ↑ Blakemore, S.-J.; den Ouden, H.; Choudhury, S.; Frith, C. (1 June 2007). "Adolescent development of the neural circuitry for thinking about intentions". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2 (2): 130–139. doi:10.1093/scan/nsm009. PMC 1948845 . PMID 17710201.

- ↑ MORIGUCHI, YOSHIYA; OHNISHI, TAKASHI; MORI, TAKEYUKI; MATSUDA, HIROSHI; KOMAKI, GEN (1 August 2007). "Changes of brain activity in the neural substrates for theory of mind during childhood and adolescence". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 61 (4): 355–363. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01687.x. PMID 17610659.

- 1 2 Burnett, S; Bird, G; Moll, J; Frith, C; Blakemore, SJ (September 2009). "Development during adolescence of the neural processing of social emotion". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 21 (9): 1736–50. doi:10.1162/jocn.2009.21121. PMC 4541723 . PMID 18823226.

- ↑ Frith, C. D (29 April 2007). "The social brain?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 362 (1480): 671–678. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.2003. PMC 1919402 . PMID 17255010.

- ↑ Zahn, R.; Moll, J.; Krueger, F.; Huey, E. D.; Garrido, G.; Grafman, J. (10 April 2007). "Social concepts are represented in the superior anterior temporal cortex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (15): 6430–6435. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.6430Z. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607061104 . PMC 1851074 . PMID 17404215.

- 1 2 McCabe, K. (2001-09-25). "A functional imaging study of cooperation in two-person reciprocal exchange". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (20): 11832–11835. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9811832M. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211415698 . PMC 58817 . PMID 11562505.

- ↑ Kahneman, Daniel (Dec 2003). "Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics". The American Economic Review. 93 (5): 1449–1475. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.194.6554 . doi:10.1257/000282803322655392. JSTOR 3132137.

- ↑ Kahneman, Daniel; Jack L. Knetsch; Richard H. Thaler (Winter 1991). "Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 5 (1): 193–206. doi: 10.1257/jep.5.1.193 . JSTOR 1942711.

- ↑ Ellsberg, Daniel (Nov 1961). "Risk, Ambiguity, and the Savage Axioms" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 75 (4): 643–669. doi:10.2307/1884324. JSTOR 1884324.

- ↑ Camerer, Colin F. (2003). Behavioral game theory experiments in strategic interaction. New York [u.a.]: Russell Sage [u.a.] ISBN 978-0-691-09039-9.

- ↑ Eisenberger, N. I. (10 October 2003). "Does Rejection Hurt? An fMRI Study of Social Exclusion". Science. 302 (5643): 290–292. Bibcode:2003Sci...302..290E. doi:10.1126/science.1089134. PMID 14551436. S2CID 21253445.

- ↑ O'Doherty, J. (16 April 2004). "Dissociable Roles of Ventral and Dorsal Striatum in Instrumental Conditioning". Science. 304 (5669): 452–454. Bibcode:2004Sci...304..452O. doi:10.1126/science.1094285. hdl: 21.11116/0000-0001-A0A8-C . PMID 15087550. S2CID 43507282.

- ↑ de Quervain, D. J.-F. (27 August 2004). "The Neural Basis of Altruistic Punishment". Science. 305 (5688): 1254–1258. Bibcode:2004Sci...305.1254D. doi:10.1126/science.1100735. PMID 15333831. S2CID 264669.

- ↑ Ferguson TJ, Stegge H. 1998. Measuring guilt in children: a rose by any other name still has thorns. In Guilt and Children, ed. J Bybee, pp. 19–74. San Diego: Academic

- 1 2 Tangney, June P. (1 January 1991). "Moral affect: The good, the bad, and the ugly". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 61 (4): 598–607. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.598. PMID 1960652.

- ↑ Eisenberg, Nancy; Fabes, Richard A.; Murphy, Bridget; Karbon, Mariss; et al. (1 January 1994). "The relations of emotionality and regulation to dispositional and situational empathy-related responding". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 66 (4): 776–797. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.4.776. PMID 8189352.

- ↑ Weiner, Bernard (2006). Social motivation, justice, and the moral emotions : an attributional approach. Mahwah, NJ [u.a.]: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 978-0-8058-5526-5.

- ↑ Weiner, Bernard (1 January 1985). "An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion". Psychological Review. 92 (4): 548–573. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.92.4.548. PMID 3903815. S2CID 6499506.

- ↑ Weiner, Bernard; Perry, Raymond P.; Magnusson, Jamie (1 January 1988). "An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 55 (5): 738–748. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.55.5.738. PMID 2974883.