Emotions are physical and mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. There is no scientific consensus on a definition. Emotions are often intertwined with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, or creativity.

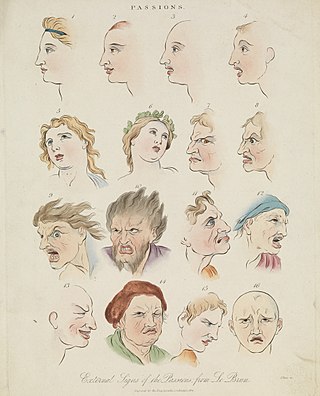

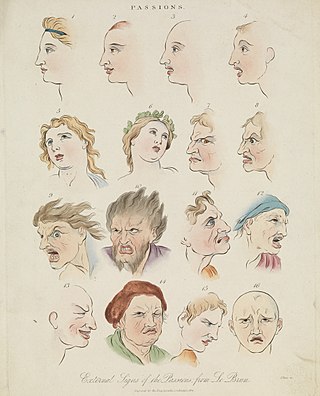

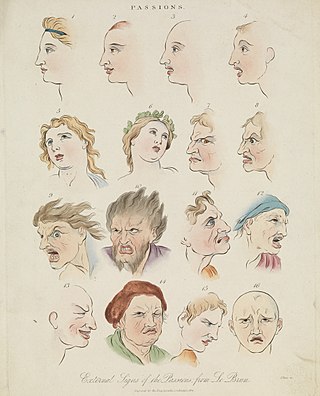

Facial expression is the motion and positioning of the muscles beneath the skin of the face. These movements convey the emotional state of an individual to observers and are a form of nonverbal communication. They are a primary means of conveying social information between humans, but they also occur in most other mammals and some other animal species.

Amusement is the state of experiencing humorous and entertaining events or situations while the person or animal actively maintains the experience, and is associated with enjoyment, happiness, laughter and pleasure. It is an emotion with positive valence and high physiological arousal.

An emotional expression is a behavior that communicates an emotional state or attitude. It can be verbal or nonverbal, and can occur with or without self-awareness. Emotional expressions include facial movements like smiling or scowling, simple behaviors like crying, laughing, or saying "thank you," and more complex behaviors like writing a letter or giving a gift. Individuals have some conscious control of their emotional expressions; however, they need not have conscious awareness of their emotional or affective state in order to express emotion.

Cultural psychology is the study of how cultures reflect and shape their members' psychological processes.

Affect, in psychology, is the underlying experience of feeling, emotion, attachment, or mood. It encompasses a wide range of emotional states and can be positive or negative. Affect is a fundamental aspect of human experience and plays a central role in many psychological theories and studies. It can be understood as a combination of three components: emotion, mood, and affectivity. In psychology, the term affect is often used interchangeably with several related terms and concepts, though each term may have slightly different nuances. These terms encompass: emotion, feeling, mood, emotional state, sentiment, affective state, emotional response, affective reactivity, disposition. Researchers and psychologists may employ specific terms based on their focus and the context of their work.

Emotionality is the observable behavioral and physiological component of emotion. It is a measure of a person's emotional reactivity to a stimulus. Most of these responses can be observed by other people, while some emotional responses can only be observed by the person experiencing them. Observable responses to emotion do not have a single meaning. A smile can be used to express happiness or anxiety, while a frown can communicate sadness or anger. Emotionality is often used by experimental psychology researchers to operationalize emotion in research studies.

Cross-cultural psychology is the scientific study of human behavior and mental processes, including both their variability and invariance, under diverse cultural conditions. Through expanding research methodologies to recognize cultural variance in behavior, language, and meaning it seeks to extend and develop psychology. Since psychology as an academic discipline was developed largely in North America and Europe, some psychologists became concerned that constructs and phenomena accepted as universal were not as invariant as previously assumed, especially since many attempts to replicate notable experiments in other cultures had varying success. Since there are questions as to whether theories dealing with central themes, such as affect, cognition, conceptions of the self, and issues such as psychopathology, anxiety, and depression, may lack external validity when "exported" to other cultural contexts, cross-cultural psychology re-examines them. It does so using methodologies designed to factor in cultural differences so as to account for cultural variance. Some critics have pointed to methodological flaws in cross-cultural psychological research, and claim that serious shortcomings in the theoretical and methodological bases used impede, rather than help, the scientific search for universal principles in psychology. Cross-cultural psychologists are turning more to the study of how differences (variance) occur, rather than searching for universals in the style of physics or chemistry.

Discrete emotion theory is the claim that there is a small number of core emotions. For example, Silvan Tomkins concluded that there are nine basic affects which correspond with what we come to know as emotions: interest, enjoyment, surprise, distress, fear, anger, shame, dissmell and disgust. More recently, Carroll Izard at the University of Delaware factor analytically delineated 12 discrete emotions labeled: Interest, Joy, Surprise, Sadness, Anger, Disgust, Contempt, Self-Hostility, Fear, Shame, Shyness, and Guilt.

Emotion classification, the means by which one may distinguish or contrast one emotion from another, is a contested issue in emotion research and in affective science. Researchers have approached the classification of emotions from one of two fundamental viewpoints:

- that emotions are discrete and fundamentally different constructs

- that emotions can be characterized on a dimensional basis in groupings

Display rules are a social group or culture's informal norms that distinguish how one should express oneself. They function as a way to maintain the social order of a given culture, creating an expected standard of behaviour to guide people in their interactions. Display rules can help to decrease situational ambiguity, help individuals to be accepted by their social groups, and can help groups to increase their group efficacy. They can be described as culturally prescribed rules that people learn early on in their lives by interactions and socializations with other people. Members of a social group learn these cultural standards at a young age which determine when one would express certain emotions, where and to what extent.

Emotional responsivity is the ability to acknowledge an affective stimuli by exhibiting emotion. It is a sharp change of emotion according to a person's emotional state. Increased emotional responsivity refers to demonstrating more response to a stimulus. Reduced emotional responsivity refers to demonstrating less response to a stimulus. Any response exhibited after exposure to the stimulus, whether it is appropriate or not, would be considered as an emotional response. Although emotional responsivity applies to nonclinical populations, it is more typically associated with individuals with schizophrenia and autism.

Extraversion and introversion are a central trait dimension in human personality theory. The terms were introduced into psychology by Carl Jung, though both the popular understanding and current psychological usage are not the same as Jung's original concept. Extraversion tends to be manifested in outgoing, talkative, energetic behavior, whereas introversion is manifested in more reflective and reserved behavior. Jung defined introversion as an "attitude-type characterised by orientation in life through subjective psychic contents", and extraversion as "an attitude-type characterised by concentration of interest on the external object".

Life satisfaction is an evaluation of a person's quality of life. It is assessed in terms of mood, relationship satisfaction, achieved goals, self-concepts, and self-perceived ability to cope with their life. Life satisfaction involves a favorable attitude towards one's life—rather than an assessment of current feelings. Life satisfaction has been measured in relation to economic standing, degree of education, experiences, residence, and other factors.

Individualistic cultures are characterized by individualism, which is the prioritization or emphasis of the individual over the entire group. In individualistic cultures, people are motivated by their own preference and viewpoints. Individualistic cultures focus on abstract thinking, privacy, self-dependence, uniqueness, and personal goals. The term individualistic culture was first used in the 1980s by Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede to describe countries and cultures that are not collectivist; Hofstede created the term individualistic culture when he created a measurement for the five dimensions of cultural values.

Subjective well-being (SWB) is a self-reported measure of well-being, typically obtained by questionnaire.

Emotion perception refers to the capacities and abilities of recognizing and identifying emotions in others, in addition to biological and physiological processes involved. Emotions are typically viewed as having three components: subjective experience, physical changes, and cognitive appraisal; emotion perception is the ability to make accurate decisions about another's subjective experience by interpreting their physical changes through sensory systems responsible for converting these observed changes into mental representations. The ability to perceive emotion is believed to be both innate and subject to environmental influence and is also a critical component in social interactions. How emotion is experienced and interpreted depends on how it is perceived. Likewise, how emotion is perceived is dependent on past experiences and interpretations. Emotion can be accurately perceived in humans. Emotions can be perceived visually, audibly, through smell and also through bodily sensations and this process is believed to be different from the perception of non-emotional material.

Cultural differences can interact with positive psychology to create great variation, potentially impacting positive psychology interventions. Culture differences have an impact on the interventions of positive psychology. Culture influences how people seek psychological help, their definitions of social structure, and coping strategies. Cross cultural positive psychology is the application of the main themes of positive psychology from cross-cultural or multicultural perspectives.

The study of the relationship between gender and emotional expression is the study of the differences between men and women in behavior that expresses emotions. These differences in emotional expression may be primarily due to cultural expectations of femininity and masculinity.

A functional account of emotions posits that emotions facilitate adaptive responses to environmental challenges. In other words, emotions are systems that respond to environmental input, such as a social or physical challenge, and produce adaptive output, such as a particular behavior. Under such accounts, emotions can manifest in maladaptive feelings and behaviors, but they are largely beneficial insofar as they inform and prepare individuals to respond to environmental challenges, and play a crucial role in structuring social interactions and relationships.