Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, especially with the aim of gaining and maintaining its sovereignty (self-governance) over its perceived homeland to create a nation-state. It holds that each nation should govern itself, free from outside interference (self-determination), that a nation is a natural and ideal basis for a polity, and that the nation is the only rightful source of political power. It further aims to build and maintain a single national identity, based on a combination of shared social characteristics such as culture, ethnicity, geographic location, language, politics, religion, traditions and belief in a shared singular history, and to promote national unity or solidarity. Nationalism, therefore, seeks to preserve and foster a nation's traditional culture. There are various definitions of a "nation", which leads to different types of nationalism. The two main divergent forms identified by scholars are ethnic nationalism and civic nationalism.

A nation is a large type of social organization where a collective identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, territory or society. Some nations are constructed around ethnicity while others are bound by political constitutions.

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and a sense of attachment to a country or state. This attachment can be a combination of different feelings for things such as the language of one's homeland, and its ethnic, cultural, political, or historical aspects. It may encompass a set of concepts closely related to nationalism, mostly civic nationalism and sometimes cultural nationalism.

Hindutva is a political ideology encompassing the cultural justification of Hindu nationalism and the belief in establishing Hindu hegemony within India. The political ideology was formulated by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar in 1922. It is used by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP), the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and other organisations, collectively called the Sangh Parivar.

Religious nationalism can be understood in a number of ways, such as nationalism as a religion itself, a position articulated by Carlton Hayes in his text Nationalism: A Religion, or as the relationship of nationalism to a particular religious belief, dogma, ideology, or affiliation. This relationship can be broken down into two aspects: the politicisation of religion and the influence of religion on politics.

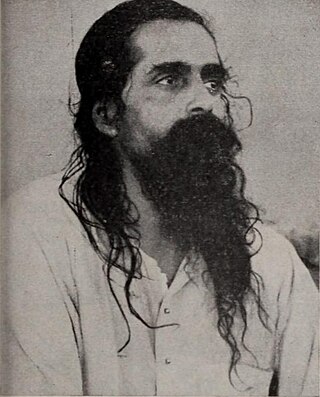

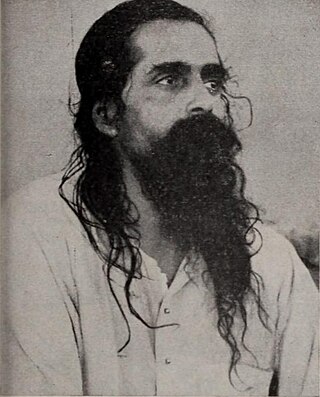

Madhav Sadashivrao Golwalkar, popularly known as Guruji, was the second Sarsanghchalak ("Chief") of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Golwalkar is considered one of the most influential and prominent figures among Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh by his followers.

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language". National identity may refer to the subjective feeling one shares with a group of people about a nation, regardless of one's legal citizenship status. National identity is viewed in psychological terms as "an awareness of difference", a "feeling and recognition of 'we' and 'they'". National identity also includes the general population and diaspora of multi-ethnic states and societies that have a shared sense of common identity identical to that of a nation while being made up of several component ethnic groups. Hyphenated ethnicities are examples of the confluence of multiple ethnic and national identities within a single person or entity.

Historiography is the study of how history is written. One pervasive influence upon the writing of history has been nationalism, a set of beliefs about political legitimacy and cultural identity. Nationalism has provided a significant framework for historical writing in Europe and in those former colonies influenced by Europe since the nineteenth century. Typically official school textbooks are based on the nationalist model and focus on the emergence, trials and successes of the forces of nationalism.

Queer nationalism is a phenomenon related both to the gay and lesbian liberation movement and nationalism. Adherents of this movement support the notion that the LGBT community forms a distinct people due to their unique culture and customs.

Civic nationalism, otherwise known as democratic nationalism and liberal nationalism, is a form of nationalism that adheres to traditional liberal values of freedom, tolerance, equality, and individual rights, and is not based on ethnocentrism. Civic nationalists often defend the value of national identity by saying that individuals need it as a partial shared aspect of their identity in order to lead meaningful, autonomous lives and that democratic polities need a national identity to function properly.

Madhukar Dattatraya Deoras, was the third Sarsanghchalak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

Among scholars of nationalism, a number of types of nationalism have been presented. Nationalism may manifest itself as part of official state ideology or as a popular non-state movement and may be expressed along civic, ethnic, language, religious or ideological lines. These self-definitions of the nation are used to classify types of nationalism, but such categories are not mutually exclusive and many nationalist movements combine some or all of these elements to varying degrees. Nationalist movements can also be classified by other criteria, such as scale and location.

John Hutchinson is a British academic. He is a reader in nationalism at the London School of Economics (LSE), in the Department of Government.

Ethnosymbolism is a school of thought in the study of nationalism that stresses the importance of symbols, myths, values and traditions in the formation and persistence of the modern nation state.

According to some scholars, a national identity of the English as the people or ethnic group dominant in England can be traced to the Anglo-Saxon period.

Hindu nationalism has been collectively referred to as the expression of social and political thought, based on the native spiritual and cultural traditions of the Indian subcontinent. "Hindu nationalism" is a simplistic translation of हिन्दू राष्ट्रवाद. It is better described as "Hindu polity".

Arab nationalism is a political ideology asserting that Arabs constitute a single nation. As a traditional nationalist ideology, it promotes Arab culture and civilization, celebrates Arab history, glorifies the Arabic language as well as Arabic literature, and calls for the rejuvenation of Arab society through total unification. It bases itself on the premise that the people of the Arab world — from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Sea — constitute one nation bound together by a common identity: ethnicity, language, culture, history, geography, and politics.

John Breuilly is professor of nationalism and ethnicity at the London School of Economics. Breuilly is the author of the pioneering Nationalism and the State (1982).

Composite nationalism is a concept that argues that the Indian nation is made up of people of diverse cultures, castes, communities, and faiths. The idea teaches that "nationalism cannot be defined by religion in India." While Indian citizens maintain their distinctive religious traditions, they are members of one united Indian nation. Composite nationalism maintains that prior to the arrival of the British into the subcontinent, no enmity between people of different religious faiths existed; and as such these artificial divisions can be overcome by Indian society.

Several scholars of nationalism support the existence of nationalism in the Middle Ages. This school of thought differs from modernism, the predominant school of thought on nationalism, which suggests that nationalism developed largely after the late 18th century and the French Revolution. Theories on the existence of nationalism in the Middle Ages may belong to the general paradigms of ethnosymbolism and primordialism (perennialism).