The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation and the European Reformation, was a major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church. Towards the end of the Renaissance, the Reformation marked the beginning of Protestantism and in turn resulted in a major schism within Western Christianity.

Girolamo Savonarola, OP or Jerome Savonarola was an ascetic Dominican friar from Ferrara and a preacher active in Renaissance Florence. He became known for his prophecies of civic glory, his advocacy of the destruction of secular art and culture, and his calls for Christian renewal. He denounced clerical corruption, despotic rule, and the exploitation of the poor.

Lelio Francesco Maria Sozzini, or simply Lelio Sozzini, was an Italian Renaissance humanist and theologian, and, alongside his nephew Fausto Sozzini, founder of the Nontrinitarian Christian belief system known as Socinianism. His doctrine was developed among the Polish Brethren in the Polish Reformed Church between the 16th and 17th centuries, and embraced by the Unitarian Church of Transylvania during the same period.

Socinianism is a Nontrinitarian Christian belief system developed and co-founded during the Protestant Reformation by the Italian Renaissance humanists and theologians Lelio Sozzini and Fausto Sozzini, uncle and nephew, respectively.

A Christian denomination is a distinct religious body within Christianity that comprises all church congregations of the same kind, identifiable by traits such as a name, particular history, organization, leadership, theological doctrine, worship style and, sometimes, a founder. It is a secular and neutral term, generally used to denote any established Christian church. Unlike a cult or sect, a denomination is usually seen as part of the Christian religious mainstream. Most Christian denominations refer to themselves as churches, whereas some newer ones tend to interchangeably use the terms churches, assemblies, fellowships, etc. Divisions between one group and another are defined by authority and doctrine; issues such as the nature of Jesus, the authority of apostolic succession, biblical hermeneutics, theology, ecclesiology, eschatology, and papal primacy may separate one denomination from another. Groups of denominations—often sharing broadly similar beliefs, practices, and historical ties—are sometimes known as "branches of Christianity". These branches differ in many ways, especially through differences in practices and belief.

Fausto Paolo Sozzini, or simply Fausto Sozzini, was an Italian Renaissance humanist and theologian, and, alongside his uncle Lelio Sozzini, founder of the Nontrinitarian Christian belief system known as Socinianism. His doctrine was developed among the Polish Brethren in the Polish Reformed Church between the 16th and 17th centuries, and embraced by the Unitarian Church of Transylvania during the same period.

Protestant Reformers were theologians whose careers, works and actions brought about the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century.

The Radical Reformation represented a response to perceived corruption both in the Catholic Church and in the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland in the 16th century, the Radical Reformation gave birth to many radical Protestant groups throughout Europe. The term covers Radical Reformers like Thomas Müntzer and Andreas Karlstadt, the Zwickau prophets, and Anabaptist groups like the Hutterites and the Mennonites.

Protestantism originated from the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. The term Protestant comes from the Protestation at Speyer in 1529, where the nobility protested against enforcement of the Edict of Worms which subjected advocates of Lutheranism to forfeit all of their property. However, the theological underpinnings go back much further, as Protestant theologians of the time cited both Church Fathers and the Apostles to justify their choices and formulations. The earliest origin of Protestantism is controversial; with some Protestants today claiming origin back to people in the early church deemed heretical such as Jovinian and Vigilantius.

The two kingdoms doctrine is a Protestant Christian doctrine that teaches that God is the ruler of the whole world and that he rules in two ways. The doctrine is held by Lutherans and represents the view of some Reformed Christians. John Calvin significantly modified Martin Luther's original two kingdoms doctrine, and certain neo-Calvinists have adopted a different view known as transformationalism.

Lutheranism as a religious movement originated in the early 16th century Holy Roman Empire as an attempt to reform the Catholic Church. The movement originated with the call for a public debate regarding several issues within the Catholic Church by Martin Luther, then a professor of Bible at the young University of Wittenberg. Lutheranism soon became a wider religious and political movement within the Holy Roman Empire owing to support from key electors and the widespread adoption of the printing press. This movement soon spread throughout northern Europe and became the driving force behind the wider Protestant Reformation. Today, Lutheranism has spread from Europe to all six populated continents.

The Protestant Reformation during the 16th century in Europe almost entirely rejected the existing tradition of Catholic art, and very often destroyed as much of it as it could reach. A new artistic tradition developed, producing far smaller quantities of art that followed Protestant agendas and diverged drastically from the southern European tradition and the humanist art produced during the High Renaissance. The Lutheran churches, as they developed, accepted a limited role for larger works of art in churches, and also encouraged prints and book illustrations. Calvinists remained steadfastly opposed to art in churches, and suspicious of small printed images of religious subjects, though generally fully accepting secular images in their homes.

In 16th-century Christianity, Protestantism came to the forefront and marked a significant change in the Christian world.

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes justification of sinners through faith alone, the teaching that salvation comes by unmerited divine grace, the priesthood of all believers, and the Bible as the sole infallible source of authority for Christian faith and practice. The five solae summarize the basic theological beliefs of mainstream Protestantism.

Protestantism in Italy comprises a minority of the country's religious population.

The discipline and administration of the Latin Church underwent important changes from 1517 to 1585 during and Counter-Reformation, specifically at the Council of Trent.

Jacob Palaeologus, also called Giacomo da Chio, was a Dominican friar who renounced his religious vows and became an antitrinitarian theologian. A polemicist against both Calvinism and Papal Power, Palaeologus cultivated a wide range of high-placed contacts and correspondents in the imperial, royal, and aristocratic households in Eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire; while formulating and propagating a radically heterodox version of Christianity, in which Jesus Christ was not to be invoked in worship, and where differences between Christianity, Islam, and Judaism were rejected as spurious fabrications. He was continually pursued by his many enemies, repeatedly escaping through his many covert supporters.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Protestantism:

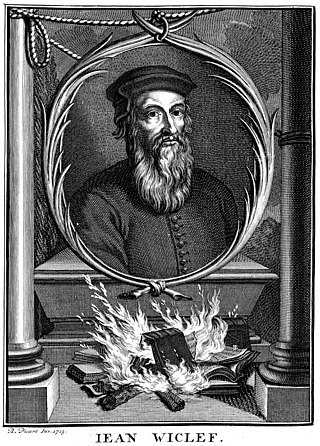

Proto-Protestantism, also called pre-Protestantism, refers to individuals and movements that propagated various ideas later associated with Protestantism before 1517, which historians usually regard as the starting year for the Reformation era. The relationship between medieval sects and Protestantism is an issue that has been debated by historians.

The Piagnoni were a group of Christians who followed the teachings of Girolamo Savonarola. The later Piagnoni remained in the Catholic Church and kept a mixture with the teachings of Catholic dogma and the teachings of Girolamo Savonarola. The name Piagnoni was given because they wept for their sins and the sins of the world.