The Diets of Nuremberg, also called the Imperial Diets of Nuremberg, took place at different times between the Middle Ages and the 17th century.

George of Brandenburg-Ansbach, known as George the Pious, was a Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach from the House of Hohenzollern.

1521 (MDXXI) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar, the 1521st year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 521st year of the 2nd millennium, the 21st year of the 16th century, and the 2nd year of the 1520s decade.

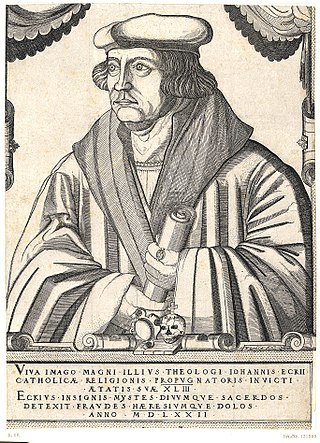

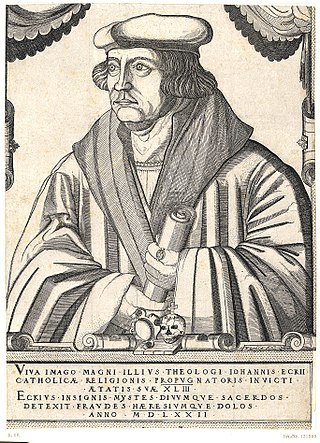

Johann Maier von Eck, often anglicized as John Eck, was a German Catholic theologian, scholastic, prelate, and a pioneer of the Counter-Reformation who was among Martin Luther's most important interlocutors and theological opponents.

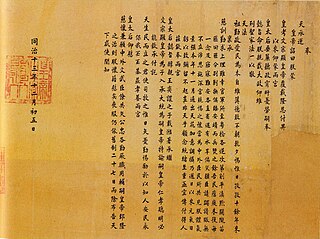

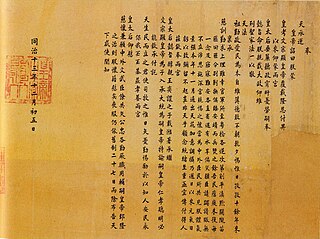

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchies, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement". Edict derives from the Latin edictum.

Frederick III, also known as Frederick the Wise, was Prince-elector of Saxony from 1486 to 1525, who is mostly remembered for the protection given to his subject Martin Luther, the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation. Frederick was the son of Ernest, Elector of Saxony and his wife Elisabeth, daughter of Albert III, Duke of Bavaria.

The Schmalkaldic War was fought within the territories of the Holy Roman Empire between the allied forces of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and Maurice, Duke of Saxony against the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League, with the forces directly loyal to Charles fighting under the command of Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba.

The diets of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the German city of Augsburg. Both an Imperial City and the residence of the Augsburg prince-bishops, the town had hosted the Estates in many such sessions since the 10th century. In 1282, the diet of Augsburg assigned the control of Austria to the House of Habsburg. In the 16th century, twelve of thirty-five imperial diets were held in Augsburg, a result of the close financial relationship between the Augsburg-based banking families such as the Fugger and the reigning Habsburg emperors, particularly Maximilian I and his grandson Charles V. Nevertheless, the meetings of 1518, 1530, 1547/48 and 1555, during the Reformation and the ensuing religious war between the Catholic emperor and the Protestant Schmalkaldic League, are especially noteworthy. With the Peace of Augsburg, the cuius regio, eius religio principle let each prince decide the religion of his subjects and inhabitants who chose not to conform could leave.

Andreas Rudolph Bodenstein von Karlstadt, better known as Andreas Karlstadt, Andreas Carlstadt or Karolostadt, in Latin, Carolstadius, or simply as Andreas Bodenstein, was a German Protestant theologian, University of Wittenberg chancellor, a contemporary of Martin Luther and a reformer of the early Reformation.

Exsurge Domine is a papal bull promulgated on 15 June 1520 by Pope Leo X. It was written in response to the teachings of Martin Luther which opposed the views of the Catholic Church. The bull censured forty-one propositions abstracted from Luther's writings, and threatened him with excommunication unless he recanted within a sixty-day period commencing upon the publication of the bull in Saxony and its neighboring regions.

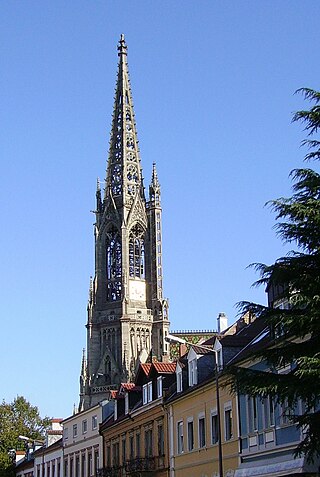

On 19 April 1529, six princes and representatives of 14 Imperial Free Cities petitioned the Imperial Diet at Speyer against an imperial ban of Martin Luther, as well as the proscription of his works and teachings, and called for the unhindered spread of the evangelical faith.

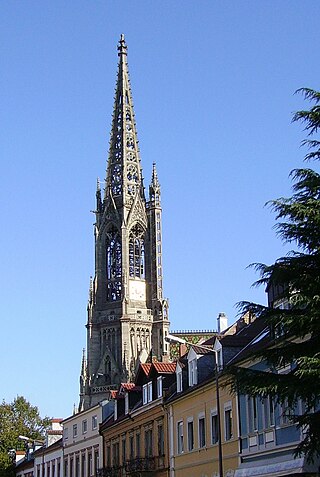

The Diet of Speyer or the Diet of Spires was a Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in 1529 in the Imperial City of Speyer. The Diet condemned the results of the Diet of Speyer of 1526 and prohibited future reformation. It resulted in the Protestation at Speyer.

The Diet of Speyer or the Diet of Spires was an Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire in 1526 in the Imperial City of Speyer in present-day Germany. The Diet's ambiguous edict resulted in a temporary suspension of the Edict of Worms and aided the expansion of Protestantism. Those results were repudiated in the Diet of Speyer (1529).

Lutheranism as a religious movement originated in the early 16th century Holy Roman Empire as an attempt to reform the Catholic Church. The movement originated with the call for a public debate regarding several issues within the Catholic Church by Martin Luther, then a professor of Bible at the young University of Wittenberg. Lutheranism soon became a wider religious and political movement within the Holy Roman Empire owing to support from key electors and the widespread adoption of the printing press. This movement soon spread throughout northern Europe and became the driving force behind the wider Protestant Reformation. Today, Lutheranism has spread from Europe to all six populated continents.

Martin Luther was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation, and his theological beliefs form the basis of Lutheranism. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in Western and Christian history.

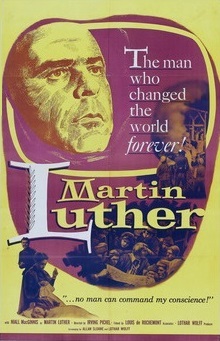

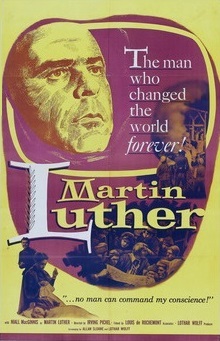

Martin Luther is a 1953 American–West German film biography of Martin Luther. It was directed by Irving Pichel,, and stars Niall MacGinnis as Luther. It was produced by Louis de Rochemont and RD-DR Corporation in collaboration with Lutheran Church Productions and Luther-Film-G.M.B.H.

Luther is a 2003 historical drama film dramatizing the life of Protestant Christian reformer Martin Luther. It is directed by Eric Till and stars Joseph Fiennes in the title role. Alfred Molina, Jonathan Firth, Claire Cox, Bruno Ganz, and Sir Peter Ustinov co-star. The film covers Luther's life from his becoming a friar in 1505, to his trial before the Diet of Augsburg in 1530. The American-German co-production was partially funded by Thrivent Financial for Lutherans, a Christian financial services company.

In 16th-century Christianity, Protestantism came to the forefront and marked a significant change in the Christian world.

Richard von Greiffenklau zu Vollrads was a German clergyman who served as Archbishop and Elector of Trier from 1511 until his death in 1531.

An imperial election was held in Cologne on 5 January 1531 to select the King of the Romans of the Holy Roman Empire. As the current emperor, Charles V, had not yet died nor abdicated, this election was conducted so as to determine his successor.