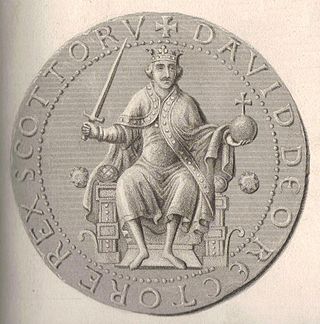

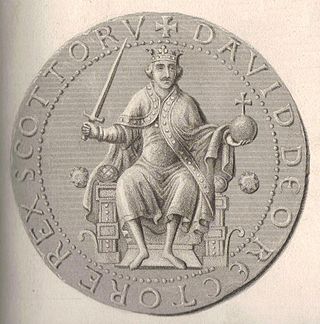

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Malcolm III and Margaret of Wessex, David spent most of his childhood in Scotland, but was exiled to England temporarily in 1093. Perhaps after 1100, he became a dependent at the court of King Henry I. There he was influenced by the Anglo-French culture of the court.

Donnchad mac Máel Coluim was King of Scots. He was son of Malcolm III and his first wife Ingibiorg Finnsdottir, widow of Thorfinn Sigurdsson.

William Forbes Skene WS FRSE FSA(Scot) DCL LLD, was a Scottish lawyer, historian and antiquary.

Saint Margaret of Scotland, also known as Margaret of Wessex, was an English princess and a Scottish queen. Margaret was sometimes called "The Pearl of Scotland". Born in the Kingdom of Hungary to the expatriate English prince Edward the Exile, Margaret and her family returned to England in 1057. Following the death of Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, her brother Edgar Ætheling was elected as King of England but never crowned. After she and her family fled north, Margaret married Malcolm III of Scotland by the end of 1070.

Ranulf de Glanvill was Chief Justiciar of England during the reign of King Henry II (1154–89) and was the probable author of Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Anglie, the earliest treatise on the laws of England.

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Burgh status was broadly analogous to borough status, found in the rest of the United Kingdom. Following local government reorganisation in 1975, the title of "royal burgh" remains in use in many towns, but now has little more than ceremonial value.

In English law, a writ of scire facias was a writ founded upon some judicial record directing the sheriff to make the record known to a specified party, and requiring the defendant to show cause why the party bringing the writ should not be able to cite that record in his own interest, or why, in the case of letters patent and grants, the patent or grant should not be annulled and vacated. In the United States, the writ has been abolished under federal law but may still be available in some state legal systems.

Henry of Bracton, also Henry de Bracton, also Henricus Bracton, or Henry Bratton also Henry Bretton was an English cleric and jurist.

The High Middle Ages of Scotland encompass Scotland in the era between the death of Domnall II in 900 AD and the death of King Alexander III in 1286, which was an indirect cause of the Wars of Scottish Independence.

Sir John Skene, Lord Curriehill (1549–1617) was a Scottish prosecutor, ambassador, and judge. He was involved in the negotiations for the marriage of James VI and Anne of Denmark.

The Davidian Revolution is a name given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregorian Reform, foundation of monasteries, Normanisation of the Scottish government, and the introduction of feudalism through immigrant Norman and Anglo-Norman knights.

The Leges inter Brettos et Scottos or Laws of the Brets and Scots was a legal codification under David I of Scotland. Only a small fragment of the original document survives, describing the penalties for several offences against people.

Books of authority is a term used by legal writers to refer to a number of early legal textbooks that are excepted from the rule that textbooks are not treated as authorities by the courts of England and Wales and other common law jurisdictions.

The Kingdom of Scotland was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a land border to the south with England. It suffered many invasions by the English, but under Robert the Bruce it fought a successful War of Independence and remained an independent state throughout the late Middle Ages. Following the annexation of the Hebrides and the Northern Isles from Norway in 1266 and 1472 respectively, and the final capture of the Royal Burgh of Berwick by England in 1482, the territory of the Kingdom of Scotland corresponded to that of modern-day Scotland, bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the southwest. In 1603, James VI of Scotland became King of England, joining Scotland with England in a personal union. In 1707, during the reign of Queen Anne, the two kingdoms were united to form the Kingdom of Great Britain under the terms of the Acts of Union.

The Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Angliae, often called Glanvill treatise, is the earliest treatise on English law. Attributed to Ranulf de Glanvill and dated 1187–1189, it was revolutionary in its systematic codification that defined legal process and introduced writs, innovations that have survived to the present day. It is considered a book of authority in English common law.

Scots law is the legal system of Scotland. It is a hybrid or mixed legal system containing civil law and common law elements, that traces its roots to a number of different historical sources. Together with English law and Northern Ireland law, it is one of the three legal systems of the United Kingdom.

The history of Scots law traces the development of Scots law from its early beginnings as a number of different custom systems among Scotland's early cultures to its modern role as one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. The various historic sources of Scots law, including custom, feudal law, canon law, Roman law and English law have created a hybrid or mixed legal system, which shares elements with English law and Northern Irish law but also has its own unique legal institutions and sources.

Government in medieval Scotland, includes all forms of politics and administration of the minor kingdoms that emerged after the departure of the Romans from central and southern Britain in the fifth century, through the development and growth of the combined Scottish and Pictish kingdom of Alba into the kingdom of Scotland, until the adoption of the reforms of the Renaissance in the fifteenth century.