The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico and Central America to the west and southwest, to the north by the Greater Antilles starting with Cuba, to the east by the Lesser Antilles, and to the south by the northern coast of South America. The Gulf of Mexico lies to the northwest.

Since the island country's independence in 1966, the economy of Barbados has been transformed from a low-income economy dependent upon sugar production into a high-income economy based on tourism and the offshore sector. Barbados went into a deep recession in the 1990s after 3 years of steady decline brought on by fundamental macroeconomic imbalances. After a painful re-adjustment process, the economy began to grow again in 1993. Growth rates have averaged between 3%–5% since then. The country's three main economic drivers are: tourism, the international business sector, and foreign direct-investment. These are supported in part by Barbados operating as a service-driven economy and an international business centre.

Tourism in Puerto Rico attracts millions of visitors each year, with more than 5.1 million passengers arriving at the Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in 2022, the main point of arrival into the island of Puerto Rico. With a $8.9 billion revenue in 2022, tourism has been a very important source of revenue for Puerto Rico for a number of decades given its favorable warm climate, beach destinations and its diversity of natural wonders, cultural and historical sites, festivals, concerts and sporting events. As Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the United States, U.S. citizens do not need a passport to enter Puerto Rico, and the ease of travel attracts many tourists from the mainland U.S. each year.

Ocho Rios is a town in the parish of Saint Ann on the north coast of Jamaica, and is more widely referred to as Ochi by locals. Beginning as a sleepy fishing village, Ocho Rios has seen explosive growth in recent decades to become a popular tourist destination featuring duty-free shopping, a cruise-ship terminal, world-renowned tourist attractions and several beaches and acclaimed resorts. In addition to being a port of call for cruise ships, Ocho Rios also hosts cargo ships at the Reynolds Pier for the exportation of sugar, limestone, and in the past, bauxite. The estimated population of the town in 2011 was 16,671, which is nearly 10% of the total population of St. Ann. The town is served by both Sangster International Airport and Ian Fleming International Airport. Scuba diving and other water sports are offered in the town's vicinity.

Saint John is one of the Virgin Islands in the Caribbean Sea and a constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), an unincorporated territory of the United States.

Punta Cana is a resort town in the easternmost region of the Dominican Republic. It was politically incorporated as the "Verón–Punta Cana township" in 2006, and it is subject to the municipality of Higüey. According to the 2022 census, this township or district had a population of 138,919 inhabitants.

Coral Bay is a small coastal settlement located 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) north of Perth, in the Shire of Carnarvon in the Gascoyne region of Western Australia.

Labadee is a port located on the northern coast of Haiti within the arrondissement of Cap-Haïtien in the Nord department. It is a private resort leased to Royal Caribbean Group, for the exclusive use of passengers of its three cruise lines: Royal Caribbean International, Celebrity Cruises, and Azamara Club Cruises, until 2050. Royal Caribbean has contributed the largest proportion of tourist revenue to Haiti since 1986, employing 300 locals, allowing another 200 to sell their wares on the premises for a fee and paying the Haitian government US$12 per tourist. The resort is completely tourist-oriented, and is guarded by a private security force. The site is fenced off from the surrounding area, and passengers are not allowed to leave the property. Food available to tourists is brought from the cruise ships. A controlled group of Haitian merchants are given sole rights to sell their merchandise and establish their businesses in the resort. Although sometimes described as an island in advertisements, it is actually a peninsula contiguous with the island of Hispaniola. The cruise ship moors to the pier at Labadee capable of servicing the Oasis class ships, which was completed in late 2009. The commercial airport that is closest to Labadee is Cap-Haïtien International Airport.

A resort town, resort city or resort destination is an urban area where tourism or vacationing is the primary component of the local culture and economy. A typical resort town has one or more actual resorts in the surrounding area. Sometimes the term resort town is used simply for a locale popular among tourists. One task force in British Columbia used the definition of an incorporated or unincorporated contiguous area where the ratio of transient rooms, measured in bed units, is greater than 60% of the permanent population.

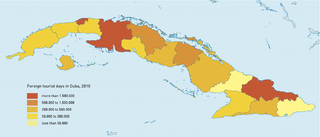

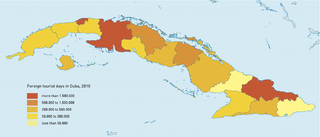

Tourism in Cuba is an industry that generates over 4.7 million arrivals as of 2018, and is one of the main sources of revenue for the island. With its favorable climate, beaches, colonial architecture and distinct cultural history, Cuba has long been an attractive destination for tourists. "Cuba treasures 253 protected areas, 257 national monuments, 7 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, 7 Natural Biosphere Reserves and 13 Fauna Refuge among other non-tourist zones."

The Port of Bridgetown, is a seaport in Bridgetown on the southwest coast of Barbados. Situated at the North-Western end of Carlisle Bay, the harbour handles all of the country's international bulk ship-based trade and commerce. In addition to international-shipping the Deep Water Harbour is the port of entry for southern-Caribbean cruise ships. The port is one of three designated ports of entry in Barbados, along with the privately owned Port Saint Charles marina and the Sir Grantley Adams International Airport. The port's time zone is GMT −4, and it handles roughly 700,000 cruise passengers and 900,000 tonnes of containerised cargo per year.

The Marieta Islands are a group of small uninhabited islands a few miles off the coast of the state of Nayarit, Mexico, located in federal waters approximately 7.9 kilometres (4.9 mi) southwest of the peninsula known as Punta de Mita, in the municipality of Bahía de Banderas.

The Caribbean or West Indies is a subregion of the Americas that includes the Caribbean Sea and its islands, some of which are surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some of which border both the Caribbean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean; the nearby coastal areas on the mainland are often also included in the region. The region is southeast of the Gulf of Mexico and the North American mainland, east of Central America, and north of South America.

Tourism in Dominica consists mostly of hiking in the rain forest and visiting cruise ships.

Tourism in Haiti is an industry that generated just under a million arrivals in 2012, and is typically one of the main sources of revenue for the nation. With its favorable climate, second-longest coastline of beaches, and most mountainous ranges in the Caribbean, waterfalls, caves, colonial architecture and distinct cultural history, Haiti has had its history as an attractive destination for tourists. However, unstable governments have long contested its history and the country's economic development throughout the 20th century.

The economy of Saint Martin, divided between the French Collectivity of Saint Martin and the Dutch Sint Maarten, is predominately dependent on tourism. For more than two centuries, the main commodity exports have generally been salt and locally grown commodities, like sugar.

A resort island is a hotel complex located on an island; in many cases one luxury hotel may own the entire island. More broadly, resort island can be defined as any island or an archipelago that contains resorts, hotels, overwater bungalows, restaurants, tourist attractions and its amenities, and might offer all-inclusive accommodations. It primary focus on tourism services and offer leisure, adventure, and amusement opportunities.

Tourism in the Dominican Republic is an important sector of the country's economy. More than 10 million tourists visited the Dominican Republic in 2023, making it the most popular tourist destination in the Caribbean and putting it in the top 5 overall in the Americas. The industry accounts for 11.6% of the nation's GDP and is a particularly important source of revenue in coastal areas of the country. The nation's tropical climate, white sand beaches, diverse mountainous landscape and colonial history attracts visitors from around the world. In 2022, the nation's tourism was named the best-performing nation post-pandemic with over 5% visitors more in comparison to pre-pandemic levels in 2019.

The economy in the Caribbean region is highly dependent on its tourism industry; in 2013, this industry constituted 14% of their total GDP. This region is largely appealing for the sun, sand, and sea scene. Despite the fact that tourism is very reliant on the natural environment of the region, it has negative environmental impacts. These impacts include marine pollution and degradation, as well as a high demand for water and energy resources. In particular, the degradation of coral reefs has a large impact on the environment of the Caribbean. Environmental damage affects the tourism industry; therefore, the tourism sector, along with the public sector, makes efforts to protect the environment for economic and ethical reasons. Although these efforts are not always effective, there are continuous efforts for improvement.

Climate changein the Caribbean poses major risks to the islands in the Caribbean. The main environmental changes expected to affect the Caribbean are a rise in sea level, stronger hurricanes, longer dry seasons and shorter wet seasons. As a result, climate change is expected to lead to changes in the economy, environment and population of the Caribbean. Temperature rise of 2 °C above preindustrial levels can increase the likelihood of extreme hurricane rainfall by four to five times in the Bahamas and three times in Cuba and Dominican Republic. Rise in sea level could impact coastal communities of the Caribbean if they are less than 3 metres (10 ft) above the sea. In Latin America and the Caribbean, it is expected that 29–32 million people may be affected by the sea level rise because they live below this threshold. The Bahamas is expected to be the most affected because at least 80% of the total land is below 10 meters elevation.