Related Research Articles

Orbital elements are the parameters required to uniquely identify a specific orbit. In celestial mechanics these elements are considered in two-body systems using a Kepler orbit. There are many different ways to mathematically describe the same orbit, but certain schemes, each consisting of a set of six parameters, are commonly used in astronomy and orbital mechanics.

The longitude of the ascending node, also known as the right ascension of the ascending node, is one of the orbital elements used to specify the orbit of an object in space. Denoted with the symbol Ω, it is the angle from a specified reference direction, called the origin of longitude, to the direction of the ascending node (☊), as measured in a specified reference plane. The ascending node is the point where the orbit of the object passes through the plane of reference, as seen in the adjacent image.

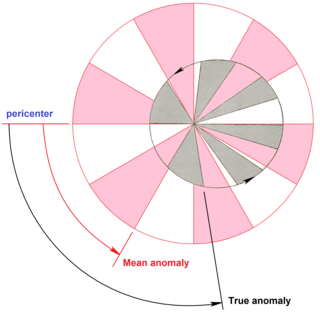

In celestial mechanics, the mean anomaly is the fraction of an elliptical orbit's period that has elapsed since the orbiting body passed periapsis, expressed as an angle which can be used in calculating the position of that body in the classical two-body problem. It is the angular distance from the pericenter which a fictitious body would have if it moved in a circular orbit, with constant speed, in the same orbital period as the actual body in its elliptical orbit.

In celestial mechanics, true anomaly is an angular parameter that defines the position of a body moving along a Keplerian orbit. It is the angle between the direction of periapsis and the current position of the body, as seen from the main focus of the ellipse.

The argument of periapsis, symbolized as ω (omega), is one of the orbital elements of an orbiting body. Parametrically, ω is the angle from the body's ascending node to its periapsis, measured in the direction of motion.

In celestial mechanics, the longitude of the periapsis, also called longitude of the pericenter, of an orbiting body is the longitude at which the periapsis would occur if the body's orbit inclination were zero. It is usually denoted ϖ.

Mean longitude is the ecliptic longitude at which an orbiting body could be found if its orbit were circular and free of perturbations. While nominally a simple longitude, in practice the mean longitude does not correspond to any one physical angle.

Orbital inclination change is an orbital maneuver aimed at changing the inclination of an orbiting body's orbit. This maneuver is also known as an orbital plane change as the plane of the orbit is tipped. This maneuver requires a change in the orbital velocity vector (delta-v) at the orbital nodes.

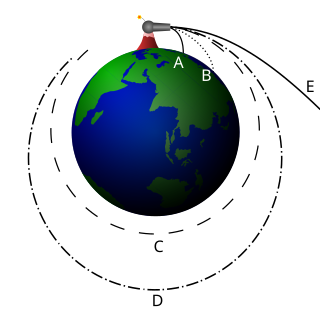

A circular orbit is an orbit with a fixed distance around the barycenter; that is, in the shape of a circle. In this case, not only the distance, but also the speed, angular speed, potential and kinetic energy are constant. There is no periapsis or apoapsis. This orbit has no radial version.

In celestial mechanics, the orbital plane of reference is the plane used to define orbital elements (positions). The two main orbital elements that are measured with respect to the plane of reference are the inclination and the longitude of the ascending node.

Spacecraft flight dynamics is the application of mechanical dynamics to model how the external forces acting on a space vehicle or spacecraft determine its flight path. These forces are primarily of three types: propulsive force provided by the vehicle's engines; gravitational force exerted by the Earth and other celestial bodies; and aerodynamic lift and drag.

The orbital plane of a revolving body is the geometric plane in which its orbit lies. Three non-collinear points in space suffice to determine an orbital plane. A common example would be the positions of the centers of a massive body (host) and of an orbiting celestial body at two different times/points of its orbit.

The perifocal coordinate (PQW) system is a frame of reference for an orbit. The frame is centered at the focus of the orbit, i.e. the celestial body about which the orbit is centered. The unit vectors and lie in the plane of the orbit. is directed towards the periapsis of the orbit and has a true anomaly of 90 degrees past the periapsis. The third unit vector is the angular momentum vector and is directed orthogonal to the orbital plane such that:

A near-equatorial orbit is an orbit that lies close to the equatorial plane of the object orbited. Such an orbit has an inclination near 0°. On Earth, such orbits lie on the celestial equator, the great circle of the imaginary celestial sphere on the same plane as the equator of Earth. A geostationary orbit is a particular type of equatorial orbit, one which is geosynchronous. A satellite in a geostationary orbit appears stationary, always at the same point in the sky, to observers on the surface of the Earth.

Orbit determination is the estimation of orbits of objects such as moons, planets, and spacecraft. One major application is to allow tracking newly observed asteroids and verify that they have not been previously discovered. The basic methods were discovered in the 17th century and have been continuously refined.

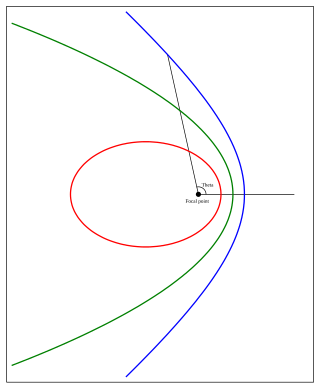

In celestial mechanics, a Kepler orbit is the motion of one body relative to another, as an ellipse, parabola, or hyperbola, which forms a two-dimensional orbital plane in three-dimensional space. A Kepler orbit can also form a straight line. It considers only the point-like gravitational attraction of two bodies, neglecting perturbations due to gravitational interactions with other objects, atmospheric drag, solar radiation pressure, a non-spherical central body, and so on. It is thus said to be a solution of a special case of the two-body problem, known as the Kepler problem. As a theory in classical mechanics, it also does not take into account the effects of general relativity. Keplerian orbits can be parametrized into six orbital elements in various ways.

In orbital mechanics, the beta angle is the angle between a satellite's orbital plane around Earth and the geocentric position of the Sun. The beta angle determines the percentage of time that a satellite in low Earth orbit (LEO) spends in direct sunlight, absorbing solar radiation. For objects launched into orbit, the solar beta angle of inclined and sun-synchronous orbits depend on launch altitude, inclination, and time.

In celestial mechanics, the argument of latitude is an angular parameter that defines the position of a body moving along a Kepler orbit. It is the angle between the ascending node and the body.

Nodal precession is the precession of the orbital plane of a satellite around the rotational axis of an astronomical body such as Earth. This precession is due to the non-spherical nature of a rotating body, which creates a non-uniform gravitational field. The following discussion relates to low Earth orbit of artificial satellites, which have no measurable effect on the motion of Earth. The nodal precession of more massive, natural satellites like the Moon is more complex.

References

- ↑ Multon, F. R. (1970). An Introduction to Celestial Mechanics (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Dover. pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Roy, A. E. (1978). Orbital Motion. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. p. 174. ISBN 0-470-99251-4.

- ↑ Brouwer, D.; Clemence, G. M. (1961). Methods of Celestial Mechanics . New York, NY: Academic Press. p. 45.