In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as a planet, moon, asteroid, or Lagrange point. Normally, orbit refers to a regularly repeating trajectory, although it may also refer to a non-repeating trajectory. To a close approximation, planets and satellites follow elliptic orbits, with the center of mass being orbited at a focal point of the ellipse, as described by Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

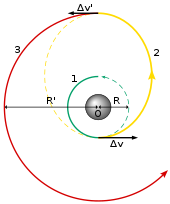

In astronautics, the Hohmann transfer orbit is an orbital maneuver used to transfer a spacecraft between two orbits of different altitudes around a central body. For example, a Hohmann transfer could be used to raise a satellite's orbit from low Earth orbit to geostationary orbit. In the idealized case, the initial and target orbits are both circular and coplanar. The maneuver is accomplished by placing the craft into an elliptical transfer orbit that is tangential to both the initial and target orbits. The maneuver uses two impulsive engine burns: the first establishes the transfer orbit, and the second adjusts the orbit to match the target.

Orbital mechanics or astrodynamics is the application of ballistics and celestial mechanics to the practical problems concerning the motion of rockets, satellites, and other spacecraft. The motion of these objects is usually calculated from Newton's laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation. Orbital mechanics is a core discipline within space-mission design and control.

In gravitationally bound systems, the orbital speed of an astronomical body or object is the speed at which it orbits around either the barycenter or, if one body is much more massive than the other bodies of the system combined, its speed relative to the center of mass of the most massive body.

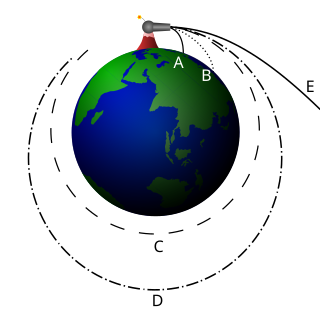

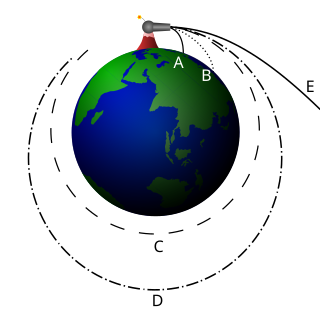

A sub-orbital spaceflight is a spaceflight in which the spacecraft reaches outer space, but its trajectory intersects the surface of the gravitating body from which it was launched. Hence, it will not complete one orbital revolution, will not become an artificial satellite nor will it reach escape velocity.

In astrodynamics and aerospace, a delta-v budget is an estimate of the total change in velocity (delta-v) required for a space mission. It is calculated as the sum of the delta-v required to perform each propulsive maneuver needed during the mission. As input to the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation, it determines how much propellant is required for a vehicle of given empty mass and propulsion system.

Orbital inclination change is an orbital maneuver aimed at changing the inclination of an orbiting body's orbit. This maneuver is also known as an orbital plane change as the plane of the orbit is tipped. This maneuver requires a change in the orbital velocity vector (delta-v) at the orbital nodes.

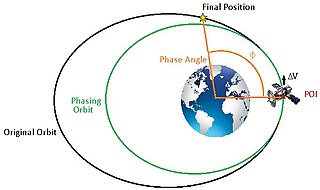

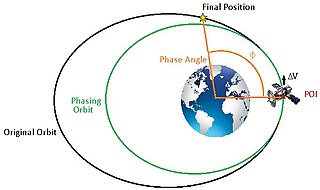

In astrodynamics, orbit phasing is the adjustment of the time-position of spacecraft along its orbit, usually described as adjusting the orbiting spacecraft's true anomaly. Orbital phasing is primarily used in scenarios where a spacecraft in a given orbit must be moved to a different location within the same orbit. The change in position within the orbit is usually defined as the phase angle, ϕ, and is the change in true anomaly required between the spacecraft's current position to the final position.

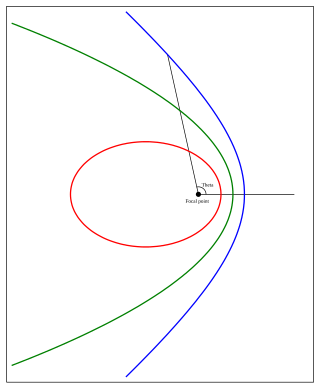

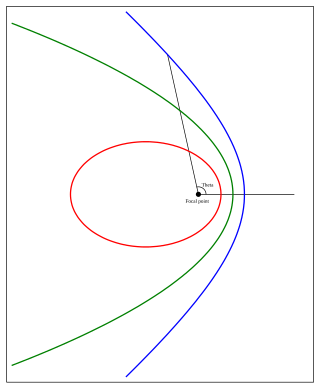

In astrodynamics or celestial mechanics a parabolic trajectory is a Kepler orbit with the eccentricity equal to 1 and is an unbound orbit that is exactly on the border between elliptical and hyperbolic. When moving away from the source it is called an escape orbit, otherwise a capture orbit. It is also sometimes referred to as a C3 = 0 orbit (see Characteristic energy).

In astrodynamics or celestial mechanics, a hyperbolic trajectory or hyperbolic orbit is the trajectory of any object around a central body with more than enough speed to escape the central object's gravitational pull. The name derives from the fact that according to Newtonian theory such an orbit has the shape of a hyperbola. In more technical terms this can be expressed by the condition that the orbital eccentricity is greater than one.

In astrodynamics or celestial mechanics, an elliptic orbit or elliptical orbit is a Kepler orbit with an eccentricity of less than 1; this includes the special case of a circular orbit, with eccentricity equal to 0. In a stricter sense, it is a Kepler orbit with the eccentricity greater than 0 and less than 1. In a wider sense, it is a Kepler orbit with negative energy. This includes the radial elliptic orbit, with eccentricity equal to 1.

A circular orbit is an orbit with a fixed distance around the barycenter; that is, in the shape of a circle. In this case, not only the distance, but also the speed, angular speed, potential and kinetic energy are constant. There is no periapsis or apoapsis. This orbit has no radial version.

In the gravitational two-body problem, the specific orbital energy of two orbiting bodies is the constant sum of their mutual potential energy and their total kinetic energy, divided by the reduced mass. According to the orbital energy conservation equation, it does not vary with time: where

In astrodynamics, an orbit equation defines the path of orbiting body around central body relative to , without specifying position as a function of time. Under standard assumptions, a body moving under the influence of a force, directed to a central body, with a magnitude inversely proportional to the square of the distance, has an orbit that is a conic section with the central body located at one of the two foci, or the focus.

In astrodynamics, the vis-viva equation, also referred to as orbital-energy-invariance law or Burgas formula, is one of the equations that model the motion of orbiting bodies. It is the direct result of the principle of conservation of mechanical energy which applies when the only force acting on an object is its own weight which is the gravitational force determined by the product of the mass of the object and the strength of the surrounding gravitational field.

In astrodynamics, the orbital eccentricity of an astronomical object is a dimensionless parameter that determines the amount by which its orbit around another body deviates from a perfect circle. A value of 0 is a circular orbit, values between 0 and 1 form an elliptic orbit, 1 is a parabolic escape orbit, and greater than 1 is a hyperbola. The term derives its name from the parameters of conic sections, as every Kepler orbit is a conic section. It is normally used for the isolated two-body problem, but extensions exist for objects following a rosette orbit through the Galaxy.

In general relativity, Schwarzschild geodesics describe the motion of test particles in the gravitational field of a central fixed mass that is, motion in the Schwarzschild metric. Schwarzschild geodesics have been pivotal in the validation of Einstein's theory of general relativity. For example, they provide accurate predictions of the anomalous precession of the planets in the Solar System and of the deflection of light by gravity.

Spacecraft flight dynamics is the application of mechanical dynamics to model how the external forces acting on a space vehicle or spacecraft determine its flight path. These forces are primarily of three types: propulsive force provided by the vehicle's engines; gravitational force exerted by the Earth and other celestial bodies; and aerodynamic lift and drag.

In astronautics, a powered flyby, or Oberth maneuver, is a maneuver in which a spacecraft falls into a gravitational well and then uses its engines to further accelerate as it is falling, thereby achieving additional speed. The resulting maneuver is a more efficient way to gain kinetic energy than applying the same impulse outside of a gravitational well. The gain in efficiency is explained by the Oberth effect, wherein the use of a reaction engine at higher speeds generates a greater change in mechanical energy than its use at lower speeds. In practical terms, this means that the most energy-efficient method for a spacecraft to burn its fuel is at the lowest possible orbital periapsis, when its orbital velocity is greatest. In some cases, it is even worth spending fuel on slowing the spacecraft into a gravity well to take advantage of the efficiencies of the Oberth effect. The maneuver and effect are named after the person who first described them in 1927, Hermann Oberth, a Transylvanian Saxon physicist and a founder of modern rocketry.

In geometry, the major axis of an ellipse is its longest diameter: a line segment that runs through the center and both foci, with ends at the two most widely separated points of the perimeter. The semi-major axis is the longest semidiameter or one half of the major axis, and thus runs from the centre, through a focus, and to the perimeter. The semi-minor axis of an ellipse or hyperbola is a line segment that is at right angles with the semi-major axis and has one end at the center of the conic section. For the special case of a circle, the lengths of the semi-axes are both equal to the radius of the circle.