In acute decompensated heart failure, the immediate goal is to re-establish adequate perfusion and oxygen delivery to end organs. This entails ensuring that airway, breathing, and circulation are adequate. Management consists of propping up the head of the patient, giving oxygen to correct hypoxemia, administering morphine, diuretics like furosemide, addition of an ACE inhibitor, use of nitrates and use of digoxin if indicated for the heart failure and if arrhythmic. [8]

Medication

Initial therapy of acute decompensated heart failure usually includes some combination of a vasodilator such as nitroglycerin, a loop diuretic such as furosemide, and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV). [9]

A number of different medications are required for people who are experiencing heart failure. Common types of medications that are prescribed for heart failure patients include ACE inhibitors, vasodilators, beta blockers, aspirin, calcium channel blockers, and cholesterol lowering medications such as statins. Depending on the type of damage a patient has suffered and the underlying cause of the heart failure, any of these drug classes or a combination of them can be prescribed. Patients with heart pumping problems will use a different medication combination than those who are experiencing problems with the heart's ability to fill properly during diastole. Potentially dangerous drug interactions can occur when different drugs mix together and work against each other. [10]

Vasodilators

Nitrates such as nitroglycerin (glyceryl trinitrate) and isosorbide dinitrate are often used as part of the initial therapy for ADHF. [9]

Another option is nesiritide, although it should only be considered if conventional therapy has been ineffective or contraindicated as it is much more expensive than nitroglycerin and has not been shown to be of any greater benefit. [11]

A 2013 Cochrane review, compared nitrates and other pharmacological, non-pharmacological, and placebo interventions. [9] The review found no significant difference between the interventions in terms of symptom control or haemodynamic stability. [9]

The National Institutes for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines do not recommend routinely offering nitrates in acute heart failure. [12]

Diuretics

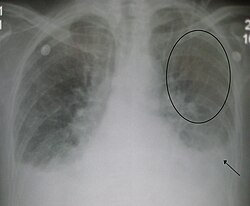

Heart failure is usually associated with a volume overloaded state. Therefore, those with evidence of fluid overload should be treated initially with intravenous loop diuretics. In the absence of symptomatic low blood pressure intravenous nitroglycerin is often used in addition to diuretic therapy to improve congestive symptoms. [8]

Volume status should still be adequately evaluated. Some heart failure patients on chronic diuretics can undergo excessive diuresis. In the case of diastolic dysfunction without systolic dysfunction, fluid resuscitation may, in fact, improve circulation by decreasing heart rate, which will allow the ventricles more time to fill. Even if the patient is edematous, fluid resuscitation may be the first line of treatment if the person's blood pressure is low. The person may, in fact, have too little fluid in their blood vessels, but if the low blood pressure is due to cardiogenic shock, the administration of additional fluid may worsen the heart failure and associated low blood pressure. If the person's circulatory volume is adequate but there is persistent evidence of inadequate end-organ perfusion, inotropes may be administered. In certain circumstances, a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) may be necessary.

Once the person is stabilized, attention can be turned to treating pulmonary edema to improve oxygenation. Intravenous furosemide is generally the first line. However, people on long-standing diuretic regimens can become tolerant, and dosages must be progressively increased. If high doses of furosemide are inadequate, boluses or continuous infusions of bumetanide may be preferred. These loop diuretics may be combined with thiazide diuretics such as oral metolazone or intravenous chlorothiazide for a synergistic effect. Intravenous preparations are physiologically preferred because of more predictable absorption due to intestinal edema, however, oral preparations can be significantly more cost effective. [13]

Others

- ACE inhibitors and ARBs

The effectiveness and safety of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) acutely in ADHF have not been well studied, but are potentially harmful. A person should be stabilized before therapy with either of these medication classes is initiated. [14] Individuals with poor kidney perfusion are especially at risk for kidney impairment inherent with these medications. [15]

- Beta-blockers

Beta-blockers are stopped or decreased in people with acutely decompensated heart failure and a low blood pressure. However, continuation of beta-blockers may be appropriate if the blood pressure is adequate. [16]

- Inotropic agents

Inotropes are indicated if low blood pressure ( SBP < 90 mmHg ) is present.

The National Institutes for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines do not recommend routinely offering inotropes in acute heart failure. [12] However, they recommend it be considered in patients with ADHF and potentially reversible caradiogenic shock. [12]

- Opioids

Opioids have traditionally been used in the treatment of the acute pulmonary edema that results from acute decompensated heart failure. A 2006 review, however, found little evidence to support this practice. [17]

The National Institutes for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines do not recommend routinely offering opioids in acute heart failure. [12]

Ultrafiltration

Ultrafiltration can be used to remove fluids in people with ADHF associated with kidney failure. Studies have found that it decreases health care utilization at 90 days. [21] One such method is aquapheresis ultra-filtration

A 2022 Cochrane review on the benefits, efficacy, and safety of ultrafiltration compared to diuretic therapy found that ultrafiltration probably reduces the incidence of heart-failure related hospitalisation in the long term. [22]

The National Institutes for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines do not recommend routinely offering ultrafiltration in acute heart failure. [12]

Surgery

In some cases, doctors recommend surgery to treat the underlying problem that led to heart failure. [23] Different procedures are available depending on the level of necessity and include coronary artery bypass surgery, heart valve repair or replacement, or heart transplantation. During these procedures, devices such as heart pumps, pacemakers, or defibrillators might be implanted. The treatment of heart disease is rapidly changing and thus new therapies for acute heart failure treatment are being introduced to save more lives from these massive attacks. [24]

Bypass surgery is performed by removing a vein from the arm or leg, or an artery from the chest and replacing the blocked artery in the heart. This allows the blood to flow more freely through the heart. Valve repair is where the valve that is causing heart failure is modified by removing excess valve tissues that cause them to close too tightly. In some cases, annuloplasty is required to replace the ring around the valves. If the repair of the valve is not possible, it is replaced by an artificial heart valve. The final step is heart replacement. When severe heart failure is present and medicines or other heart procedures are not effective, the diseased heart needs to be replaced.

Another common procedure used to treat heart failure patients is an angioplasty. Is a procedure used to improve the symptoms of coronary artery disease (CAD), reduce the damage to the heart muscle after a heart attack, and reduce the risk of death in some patients. [25]

A pacemaker is a small device that's placed in the chest or abdomen to help control abnormal heart rhythms. [26] They work by sending electric pulses to the heart to prompt it to beat at a rate that is considered to be normal and are used to treat patients with arrhythmias. They can be used to treat hearts that are classified as either a tachycardia that beats too fast, or a bradycardia that beats too slow.