A supermassive black hole is the largest type of black hole, with its mass being on the order of hundreds of thousands, or millions to billions, of times the mass of the Sun (M☉). Black holes are a class of astronomical objects that have undergone gravitational collapse, leaving behind spheroidal regions of space from which nothing can escape, including light. Observational evidence indicates that almost every large galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center. For example, the Milky Way galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center, corresponding to the radio source Sagittarius A*. Accretion of interstellar gas onto supermassive black holes is the process responsible for powering active galactic nuclei (AGNs) and quasars.

The Galactic Center is the barycenter of the Milky Way and a corresponding point on the rotational axis of the galaxy. Its central massive object is a supermassive black hole of about 4 million solar masses, which is called Sagittarius A*, a compact radio source which is almost exactly at the galactic rotational center. The Galactic Center is approximately 8 kiloparsecs (26,000 ly) away from Earth in the direction of the constellations Sagittarius, Ophiuchus, and Scorpius, where the Milky Way appears brightest, visually close to the Butterfly Cluster (M6) or the star Shaula, south to the Pipe Nebula.

In astronomy, a galactic bulge is a tightly packed group of stars within a larger star formation. The term almost exclusively refers to the central group of stars found in most spiral galaxies. Bulges were historically thought to be elliptical galaxies that happened to have a disk of stars around them, but high-resolution images using the Hubble Space Telescope have revealed that many bulges lie at the heart of a spiral galaxy. It is now thought that there are at least two types of bulges: bulges that are like ellipticals and bulges that are like spiral galaxies.

An intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH) is a class of black hole with mass in the range 102–105 solar masses: significantly higher than stellar black holes but lower than the 105–109 solar mass supermassive black holes. Several IMBH candidate objects have been discovered in the Milky Way galaxy and others nearby, based on indirect gas cloud velocity and accretion disk spectra observations of various evidentiary strength.

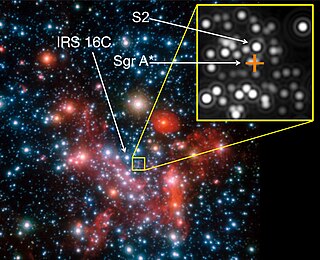

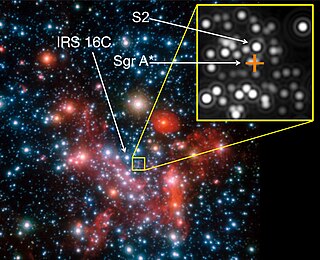

Sagittarius A*, abbreviated Sgr A*, is the supermassive black hole at the Galactic Center of the Milky Way. Viewed from Earth, it is located near the border of the constellations Sagittarius and Scorpius, about 5.6° south of the ecliptic, visually close to the Butterfly Cluster (M6) and Lambda Scorpii.

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes the Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked eye.

GCIRS 13E is an infrared and radio object near the Galactic Center. It is believed to be a cluster of hot massive stars, possibly containing an intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH) at its center.

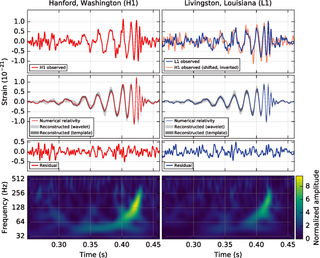

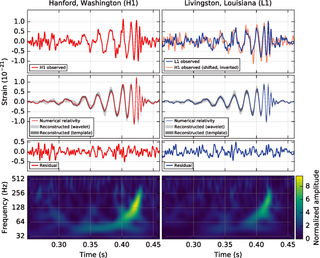

Gravitational-wave astronomy is a subfield of astronomy concerned with the detection and study of gravitational waves emitted by astrophysical sources.

Reinhard Genzel is a German astrophysicist, co-director of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, a professor at LMU and an emeritus professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He was awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics "for the discovery of a supermassive compact object at the centre of our galaxy", which he shared with Andrea Ghez and Roger Penrose. In a 2021 interview given to Federal University of Pará in Brazil, Genzel recalls his journey as a physicist; the influence of his father, Ludwig Genzel; his experiences working with Charles H. Townes; and more.

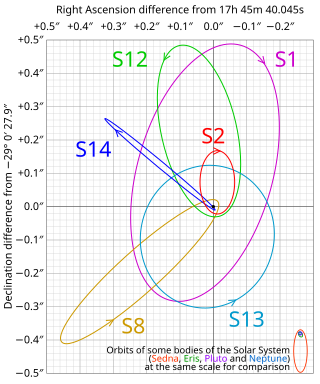

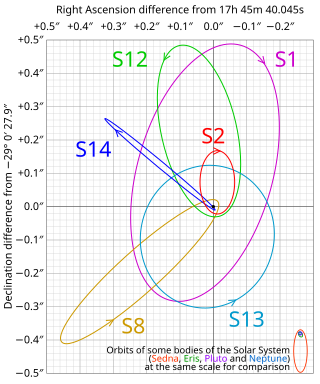

S2, also known as S0–2, is a star in the star cluster close to the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), orbiting it with a period of 16.0518 years, a semi-major axis of about 970 au, and a pericenter distance of 17 light hours – an orbit with a period only about 30% longer than that of Jupiter around the Sun, but coming no closer than about four times the distance of Neptune from the Sun. The mass when the star first formed is estimated by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) to have been approximately 14 M☉. Based on its spectral type, it probably has a mass of 10 to 15 solar masses.

Sagittarius A is a complex radio source at the center of the Milky Way, which contains a supermassive black hole. It is located between Scorpius and Sagittarius, and is hidden from view at optical wavelengths by large clouds of cosmic dust in the spiral arms of the Milky Way. The dust lane that obscures the Galactic Center from a vantage point around the Sun causes the Great Rift through the bright bulge of the galaxy.

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) is a large telescope array consisting of a global network of radio telescopes. The EHT project combines data from several very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI) stations around Earth, which form a combined array with an angular resolution sufficient to observe objects the size of a supermassive black hole's event horizon. The project's observational targets include the two black holes with the largest angular diameter as observed from Earth: the black hole at the center of the supergiant elliptical galaxy Messier 87, and Sagittarius A* at the center of the Milky Way.

S55 is a star that is located very close to the centre of the Milky Way, near the radio source Sagittarius A*, orbiting it with an orbital period of 12.8 years. Until 2019, when the star S62 became the new record holder, it was the star with the shortest known period orbiting the black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. This beat the record of 16 years previously set by S2. The star was identified by a University of California, Los Angeles team headed by Andrea M. Ghez. At its periapsis, its speed reaches 1.7% of the speed of light. At that point it is 246 astronomical units from the centre, while the black hole radius is only a small fraction of that size. It passed that point in 2022 and will be there again in 2034.

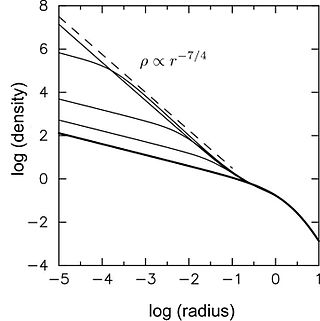

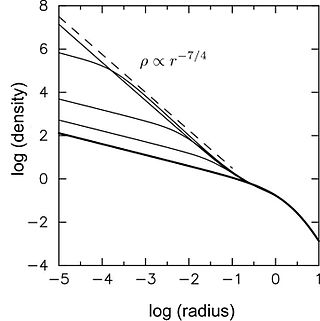

Bahcall–Wolf cusp refers to a particular distribution of stars around a massive black hole at the center of a galaxy or globular cluster. If the nucleus containing the black hole is sufficiently old, exchange of orbital energy between stars drives their distribution toward a characteristic form, such that the density of stars, ρ, varies with distance from the black hole, r, as

Robert Michael Rich is an American astrophysicist. He obtained his B.A. at Pomona College in 1979 and earned his Ph.D. from the California Institute of Technology in 1986 under thesis supervisor Jeremy R. Mould. He was a Carnegie Fellow at Carnegie/DTM until 1988 when he joined the faculty of Columbia University where he was the doctoral thesis adviser to Neil deGrasse Tyson, and is on the faculty of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Mark R. Morris is an American astrophysicist. He earned his B.A. magna cum laude at the University of California, Riverside and his Ph.D. in Physics at the University of Chicago. He did his postdoctoral work at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory, California Institute of Technology, and was on the faculty of the Department of Physics at Columbia University. Since 1985 he has been a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of California, Los Angeles.

S62 is a star in the cluster surrounding Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way. S62 orbits Sgr A* in 9.9 years, the shortest known orbital period of any star around Sgr A*. The previous record holder, S55 has a 12.8-year period.

The Sagittarius A* cluster is the cluster of stars in close orbit around Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. The individual stars are often listed as "S-stars", but their names and IDs are not formalized, and stars can have different numbers in different catalogues.

Frank Eisenhauer is a German astronomer and astrophysicist, a director of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE), and a professor at Technical University of Munich. He is best known for his contributions to interferometry and spectroscopy and the study of the black hole at the centre of the Milky Way.