The pleural cavity, pleural space, or interpleural space is the potential space between the pleurae of the pleural sac that surrounds each lung. A small amount of serous pleural fluid is maintained in the pleural cavity to enable lubrication between the membranes, and also to create a pressure gradient.

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other symptoms may include shortness of breath, cough, fever, or weight loss, depending on the underlying cause. Pleurisy can be caused by a variety of conditions, including viral or bacterial infections, autoimmune disorders, and pulmonary embolism.

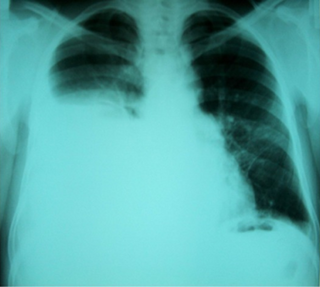

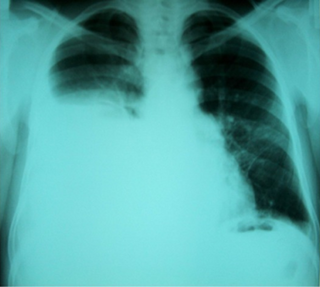

A pleural effusion is accumulation of excessive fluid in the pleural space, the potential space that surrounds each lung. Under normal conditions, pleural fluid is secreted by the parietal pleural capillaries at a rate of 0.6 millilitre per kilogram weight per hour, and is cleared by lymphatic absorption leaving behind only 5–15 millilitres of fluid, which helps to maintain a functional vacuum between the parietal and visceral pleurae. Excess fluid within the pleural space can impair inspiration by upsetting the functional vacuum and hydrostatically increasing the resistance against lung expansion, resulting in a fully or partially collapsed lung.

Asbestosis is long-term inflammation and scarring of the lungs due to asbestos fibers. Symptoms may include shortness of breath, cough, wheezing, and chest tightness. Complications may include lung cancer, mesothelioma, and pulmonary heart disease.

Pleural empyema is a collection of pus in the pleural cavity caused by microorganisms, usually bacteria. Often it happens in the context of a pneumonia, injury, or chest surgery. It is one of the various kinds of pleural effusion. There are three stages: exudative, when there is an increase in pleural fluid with or without the presence of pus; fibrinopurulent, when fibrous septa form localized pus pockets; and the final organizing stage, when there is scarring of the pleura membranes with possible inability of the lung to expand. Simple pleural effusions occur in up to 40% of bacterial pneumonias. They are usually small and resolve with appropriate antibiotic therapy. If however an empyema develops additional intervention is required.

Atelectasis is the partial collapse or closure of a lung resulting in reduced or absent gas exchange. It is usually unilateral, affecting part or all of one lung. It is a condition where the alveoli are deflated down to little or no volume, as distinct from pulmonary consolidation, in which they are filled with liquid. It is often referred to informally as a collapsed lung, although more accurately it usually involves only a partial collapse, and that ambiguous term is also informally used for a fully collapsed lung caused by a pneumothorax.

A hemothorax is an accumulation of blood within the pleural cavity. The symptoms of a hemothorax may include chest pain and difficulty breathing, while the clinical signs may include reduced breath sounds on the affected side and a rapid heart rate. Hemothoraces are usually caused by an injury, but they may occur spontaneously due to cancer invading the pleural cavity, as a result of a blood clotting disorder, as an unusual manifestation of endometriosis, in response to Pneumothorax, or rarely in association with other conditions.

A chylothorax is an abnormal accumulation of chyle, a type of lipid-rich lymph, in the space surrounding the lung. The lymphatics of the digestive system normally returns lipids absorbed from the small bowel via the thoracic duct, which ascends behind the esophagus to drain into the left brachiocephalic vein. If normal thoracic duct drainage is disrupted, either due to obstruction or rupture, chyle can leak and accumulate within the negative-pressured pleural space. In people on a normal diet, this fluid collection can sometimes be identified by its turbid, milky white appearance, since chyle contains emulsified triglycerides.

Lung abscess is a type of liquefactive necrosis of the lung tissue and formation of cavities containing necrotic debris or fluid caused by microbial infection.

Respiratory diseases, or lung diseases, are pathological conditions affecting the organs and tissues that make gas exchange difficult in air-breathing animals. They include conditions of the respiratory tract including the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, alveoli, pleurae, pleural cavity, the nerves and muscles of respiration. Respiratory diseases range from mild and self-limiting, such as the common cold, influenza, and pharyngitis to life-threatening diseases such as bacterial pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, tuberculosis, acute asthma, lung cancer, and severe acute respiratory syndromes, such as COVID-19. Respiratory diseases can be classified in many different ways, including by the organ or tissue involved, by the type and pattern of associated signs and symptoms, or by the cause of the disease.

Mediastinitis is inflammation of the tissues in the mid-chest, or mediastinum. It can be either acute or chronic. It is thought to be due to four different etiologies:

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) is a form of lung disease characterized by progressive scarring of both lungs. The scarring (fibrosis) involves the pulmonary interstitium. UIP is thus classified as a form of interstitial lung disease.

Pleural disease occurs in the pleural space, which is the thin fluid-filled area in between the two pulmonary pleurae in the human body. There are several disorders and complications that can occur within the pleural area, and the surrounding tissues in the lung.

Rheumatoid lung disease is a disease of the lung associated with RA, rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid lung disease is characterized by pleural effusion, pulmonary fibrosis, lung nodules and pulmonary hypertension. Common symptoms associated with the disease include shortness of breath, cough, chest pain and fever. It is estimated that about one quarter of people with rheumatoid arthritis develop this disease, which are more likely to develop among elderly men with a history of smoking.

Tumor-like disorders of the lung pleura are a group of conditions that on initial radiological studies might be confused with malignant lesions. Radiologists must be aware of these conditions in order to avoid misdiagnosing patients. Examples of such lesions are: pleural plaques, thoracic splenosis, catamenial pneumothorax, pleural pseudotumor, diffuse pleural thickening, diffuse pulmonary lymphangiomatosis and Erdheim–Chester disease.

Asbestos-related diseases are disorders of the lung and pleura caused by the inhalation of asbestos fibres. Asbestos-related diseases include non-malignant disorders such as asbestosis, diffuse pleural thickening, pleural plaques, pleural effusion, rounded atelectasis and malignancies such as lung cancer and malignant mesothelioma.

Tracheal deviation is a clinical sign that results from unequal intrathoracic pressure within the chest cavity. It is most commonly associated with traumatic pneumothorax, but can be caused by a number of both acute and chronic health issues, such as pneumonectomy, atelectasis, pleural effusion, fibrothorax, or some cancers and certain lymphomas associated with the mediastinal lymph nodes.

Thoracic endometriosis is a rare form of endometriosis where endometrial-like tissue is found in the lung parenchyma and/or the pleura. It can be classified as either pulmonary, or pleural, respectively. Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of tissue similar to the lining of the uterus forming abnormal growths elsewhere in the body. Usually these growths are found in the pelvis, between the rectum and the uterus, the ligaments of the pelvis, the bladder, the ovaries, and the sigmoid colon. The cause is not known. The most common symptom of thoracic endometriosis is chest pain occurring right before or during menstruation. Diagnosis is based on clinical history and examination, augmented with X-ray, CT scan, and magnetic resonance imaging of the chest. Treatment options include surgery and hormones.

Hepatic hydrothorax is a rare form of pleural effusion that occurs in people with liver cirrhosis. It is defined as an effusion of over 500 mL in people with liver cirrhosis that is not caused by heart, lung, or pleural disease. It is found in 5–10% of people with liver cirrhosis and 2–3% of people with pleural effusions. It is much more common on the right side, with 85% of cases occurring on the right, 13% on the left, and 2% on both. Although it is most common in people with severe ascites, it can also occur in people with mild or no ascites. Symptoms are not specific and mostly involve the respiratory system.

Lung surgery is a type of thoracic surgery involving the repair or removal of lung tissue, and can be used to treat a variety of conditions ranging from lung cancer to pulmonary hypertension. Common operations include anatomic and nonanatomic resections, pleurodesis and lung transplants. Though records of lung surgery date back to the Classical Age, new techniques such as VATS continue to be developed.