| Horseshoe Canyon Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Campanian-Maastrichtian ~ [1] | |

Horseshoe Canyon Formation at Horsethief Canyon, near Drumheller. The dark bands are coal seams. | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Edmonton Group |

| Sub-units | Strathmore Member, Drumheller Member, Horsethief Member, Morrin Member, Tolman Member, Carbon Member, Whitemud Member |

| Underlies | Battle Formation, Scollard Formation |

| Overlies | Bearpaw Formation |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Sandstone |

| Other | Shale, coal |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 51°25′24″N112°53′18″W / 51.42333°N 112.88833°W |

| Region | Alberta |

| Country | Canada |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Horseshoe Canyon |

| Named by | E.J.W. Irish, 1970 |

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is a stratigraphic unit of the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin in southwestern Alberta. [2] [3] It takes its name from Horseshoe Canyon, an area of badlands near Drumheller.

Contents

- Oil/gas production

- Biostratigraphy

- Dinosaurs

- Ornithischians

- Theropods

- Other animals

- Mammals

- Other reptiles

- Fish

- See also

- References

- Bibliography

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is part of the Edmonton Group. In its type section (Red Deer River Valley at Drumheller), it is ~250 metres (820 ft) thick, but further west the formation is older and thicker, exceeding 500 metres (1,600 ft) near Calgary. [4] It is of Late Cretaceous age, Campanian to early Maastrichtian stage (Edmontonian Land-Mammal Age), and is composed of mudstone, sandstone, carbonaceous shales, and coal seams. A variety of depositional environments are represented in the succession, including floodplains, estuarine channels, and coal swamps, which have yielded a diversity of fossil material. Tidally-influenced estuarine point bar deposits are easily recognizable as Inclined Heterolithic Stratification (IHS). Brackish-water trace fossil assemblages occur within these bar deposits and demonstrate periodic incursion of marine waters into the estuaries.

The Horseshoe Canyon Formation crops out extensively in the area around Drumheller, as well as farther north along the Red Deer River near Trochu and along the North Saskatchewan River in Edmonton. [2] It is overlain by the Battle and Scollard formations. [4] The Drumheller Coal Zone, located in the lower part of the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, was mined for sub-bituminous coal in the Drumheller area from 1911 to 1979, and the Atlas Coal Mine in Drumheller has been preserved as a National Historic Site. [5] In more recent times, the Horseshoe Canyon Formation has become a major target for coalbed methane (CBM) production.

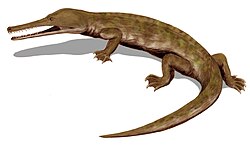

Dinosaurs found in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation include Albertavenator , Albertosaurus , Anchiceratops , Anodontosaurus , Arrhinoceratops , Atrociraptor , Epichirostenotes , Edmontonia , Edmontosaurus , Hypacrosaurus , Ornithomimus , Pachyrhinosaurus , Parksosaurus , Saurolophus , and Struthiomimus . Other finds have included mammals such as Didelphodon coyi, non-dinosaur reptiles, amphibians, fish, marine and terrestrial invertebrates and plant fossils. Reptiles such as turtles and crocodilians are rare in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, and this was thought to reflect the relatively cool climate which prevailed at the time. A study by Quinney et al. (2013) however, showed that the decline in turtle diversity, which was previously attributed to climate, coincided instead with changes in soil drainage conditions, and was limited by aridity, landscape instability, and migratory barriers. [6]