| Influenza A virus | |

|---|---|

| |

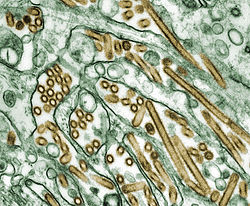

| Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (seen in gold) grown in MDCK cells (seen in green) | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Insthoviricetes |

| Order: | Articulavirales |

| Family: | Orthomyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Alphainfluenzavirus |

| Species: | Influenza A virus |

| Notable strains | |

Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 (A/H5N1) is a subtype of the influenza A virus, which causes the disease avian influenza (often referred to as "bird flu"). It is enzootic (maintained in the population) in many bird populations, and also panzootic (affecting animals of many species over a wide area). [1] A/H5N1 virus can also infect mammals (including humans) that have been exposed to infected birds; in these cases, symptoms are frequently severe or fatal. [2]

Contents

- Signs and symptoms

- Humans

- Virology

- Influenza virus nomenclature

- Genetic structure

- Prevention and treatment

- Vaccine

- Treatment

- Epidemiology

- History

- Pandemic potential

- Surveillance

- Transmission and prevention

- Mortality

- Outbreaks

- 1959–1997

- 2003

- 2004

- 2005

- 2006

- 2007

- 2008–2019

- 2020–2025

- Mammalian infections

- Research

- H5N1 transmission studies in ferrets (2011)

- See also

- Notes

- References

- Citations

- Sources

- External links

A/H5N1 virus is shed in the saliva, mucus, and feces of infected birds; other infected animals may shed bird flu viruses in respiratory secretions and other body fluids (such as milk). [3] The virus can spread rapidly through poultry flocks and among wild birds. [3] An estimated half billion farmed birds have been slaughtered in efforts to contain the virus. [2]

Symptoms of A/H5N1 influenza vary according to both the strain of virus underlying the infection and on the species of bird or mammal affected. [4] [5] Classification as either Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI) or High Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) is based on the severity of symptoms in domestic chickens and does not predict the severity of symptoms in other species. [6] Chickens infected with LPAI A/H5N1 virus display mild symptoms or are asymptomatic, whereas HPAI A/H5N1 causes serious breathing difficulties, a significant drop in egg production, and sudden death. [7]

In mammals, including humans, A/H5N1 influenza (whether LPAI or HPAI) is rare. Symptoms of infection vary from mild to severe, including fever, diarrhea, and cough. [5] Human infections with A/H5N1 virus have been reported in 23 countries since 1997, resulting in severe pneumonia and death in about 50% of cases. [8] Between 2003 and February 2025, the World Health Organization has recorded 972 cases of confirmed H5N1 influenza, leading to 468 deaths. [9] The true fatality rate may be lower because some cases with mild symptoms may not have been identified as H5N1. [10]

A/H5N1 influenza virus was first identified in farmed birds in southern China in 1996. [11] Between 1996 and 2018, A/H5N1 coexisted in bird populations with other subtypes of the virus, but since then, the highly pathogenic subtype HPAI A(H5N1) has become the dominant strain in bird populations worldwide. [12] Some strains of A/H5N1 which are highly pathogenic to chickens have adapted to cause mild symptoms in ducks and geese, [13] [6] and are able to spread rapidly through bird migration. [14] Mammal species in addition to humans that have been recorded with H5N1 infection include cattle, seals, goats, and skunks. [15]

Due to the high lethality and virulence of HPAI A(H5N1), its worldwide presence, its increasingly diverse host reservoir, and its significant ongoing mutations, the H5N1 virus is regarded as the world's largest pandemic threat. [16] Domestic poultry may potentially be protected from specific strains of the virus by vaccination. [17] In the event of a serious outbreak of H5N1 flu among humans, health agencies have prepared "candidate" vaccines that may be used to prevent infection and control the outbreak; however, it could take several months to ramp up mass production. [3] [18] [19]