In vector calculus and physics, a vector field is an assignment of a vector to each point in a subset of space. A vector field in the plane, can be visualised as a collection of arrows with a given magnitude and direction, each attached to a point in the plane. Vector fields are often used to model, for example, the speed and direction of a moving fluid throughout space, or the strength and direction of some force, such as the magnetic or gravitational force, as it changes from one point to another point.

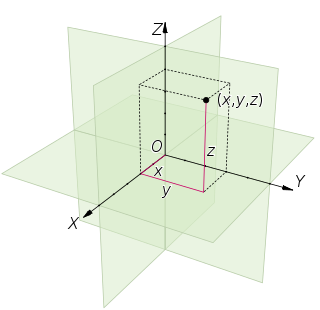

In mathematics, a plane is a flat, two-dimensional surface that extends infinitely far. A plane is the two-dimensional analogue of a point, a line and three-dimensional space. Planes can arise as subspaces of some higher-dimensional space, as with a room's walls extended infinitely far, or they may enjoy an independent existence in their own right, as in the setting of Euclidean geometry.

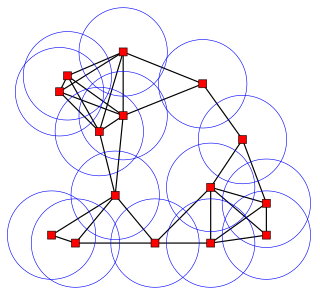

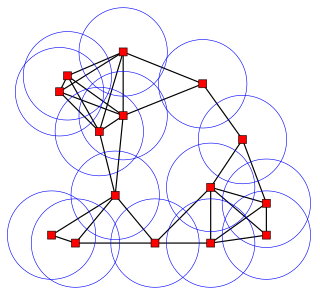

Packing problems are a class of optimization problems in mathematics that involve attempting to pack objects together into containers. The goal is to either pack a single container as densely as possible or pack all objects using as few containers as possible. Many of these problems can be related to real life packaging, storage and transportation issues. Each packing problem has a dual covering problem, which asks how many of the same objects are required to completely cover every region of the container, where objects are allowed to overlap.

In mathematics, an integral polytope has an associated Ehrhart polynomial that encodes the relationship between the volume of a polytope and the number of integer points the polytope contains. The theory of Ehrhart polynomials can be seen as a higher-dimensional generalization of Pick's theorem in the Euclidean plane.

In mathematics, the Leech lattice is an even unimodular lattice Λ24 in 24-dimensional Euclidean space, which is one of the best models for the kissing number problem. It was discovered by John Leech (1967). It may also have been discovered by Ernst Witt in 1940.

In geometry, a sphere packing is an arrangement of non-overlapping spheres within a containing space. The spheres considered are usually all of identical size, and the space is usually three-dimensional Euclidean space. However, sphere packing problems can be generalised to consider unequal spheres, spaces of other dimensions or to non-Euclidean spaces such as hyperbolic space.

Discrete geometry and combinatorial geometry are branches of geometry that study combinatorial properties and constructive methods of discrete geometric objects. Most questions in discrete geometry involve finite or discrete sets of basic geometric objects, such as points, lines, planes, circles, spheres, polygons, and so forth. The subject focuses on the combinatorial properties of these objects, such as how they intersect one another, or how they may be arranged to cover a larger object.

In geometry, close-packing of equal spheres is a dense arrangement of congruent spheres in an infinite, regular arrangement. Carl Friedrich Gauss proved that the highest average density – that is, the greatest fraction of space occupied by spheres – that can be achieved by a lattice packing is

In coding theory, block codes are a large and important family of error-correcting codes that encode data in blocks. There is a vast number of examples for block codes, many of which have a wide range of practical applications. The abstract definition of block codes is conceptually useful because it allows coding theorists, mathematicians, and computer scientists to study the limitations of all block codes in a unified way. Such limitations often take the form of bounds that relate different parameters of the block code to each other, such as its rate and its ability to detect and correct errors.

In mathematics, the E8 lattice is a special lattice in R8. It can be characterized as the unique positive-definite, even, unimodular lattice of rank 8. The name derives from the fact that it is the root lattice of the E8 root system.

Three-dimensional space is a geometric setting in which three values are required to determine the position of an element. This is the informal meaning of the term dimension.

In four-dimensional Euclidean geometry, the 16-cell honeycomb is one of the three regular space-filling tessellations, represented by Schläfli symbol {3,3,4,3}, and constructed by a 4-dimensional packing of 16-cell facets, three around every face.

The 8-demicubic honeycomb, or demiocteractic honeycomb is a uniform space-filling tessellation in Euclidean 8-space. It is constructed as an alternation of the regular 8-cubic honeycomb.

Two-dimensional space is a geometric setting in which two values are required to determine the position of an element. The set ℝ2 of pairs of real numbers with appropriate structure often serves as the canonical example of a two-dimensional Euclidian space. For a generalization of the concept, see dimension.

Polyhedral combinatorics is a branch of mathematics, within combinatorics and discrete geometry, that studies the problems of counting and describing the faces of convex polyhedra and higher-dimensional convex polytopes.

In mathematics, a sequence of n real numbers can be understood as a location in n-dimensional space. When n = 8, the set of all such locations is called 8-dimensional space. Often such spaces are studied as vector spaces, without any notion of distance. Eight-dimensional Euclidean space is eight-dimensional space equipped with the Euclidean metric.

Ideal lattices are a special class of lattices and a generalization of cyclic lattices. Ideal lattices naturally occur in many parts of number theory, but also in other areas. In particular, they have a significant place in cryptography. Micciancio defined a generalization of cyclic lattices as ideal lattices. They can be used in cryptosystems to decrease by a square root the number of parameters necessary to describe a lattice, making them more efficient. Ideal lattices are a new concept, but similar lattice classes have been used for a long time. For example cyclic lattices, a special case of ideal lattices, are used in NTRUEncrypt and NTRUSign.

In the mathematical fields of numerical analysis and approximation theory, box splines are piecewise polynomial functions of several variables. Box splines are considered as a multivariate generalization of basis splines (B-splines) and are generally used for multivariate approximation/interpolation. Geometrically, a box spline is the shadow (X-ray) of a hypercube projected down to a lower-dimensional space. Box splines and simplex splines are well studied special cases of polyhedral splines which are defined as shadows of general polytopes.

Short integer solution (SIS) and ring-SIS problems are two average-case problems that are used in lattice-based cryptography constructions. Lattice-based cryptography began in 1996 from a seminal work by Ajtai who presented a family of one-way functions based on SIS problem. He showed that it is secure in an average case if the shortest vector problem is hard in a worst-case scenario.