Constitution

The constitution of 2011 replaced that of 1949.

The law of Hungary is civil law. [1] It was first codified during the socialist period. [2]

The constitution of 2011 replaced that of 1949.

The legislature is the Magyar Országgyűlés (English: National Assembly). [3] There was formerly a Diet of Hungary.

Legislation [4] includes Acts (Hungarian: törvény [5] or törvények). [6] [7]

There is a Supreme Court, a Constitutional Court [3] and a Central District Court of Pest. [24] There was a Chief Justice of Hungary.

There is a Hungarian Bar Association [25] (Hungarian: Magyar Ügyvédi Kamara). [26] Legislation relating to legal practitioners includes Act XI of 1998. [27] [28]

The law of Hungary includes criminal law. [29] Legislation on this subject has included Act IV of 1978 on criminal code.

Legislation on criminal procedure has included Act III of 1951, [30] [31] [32] Act I of 1973 on criminal procedure [16] and Act XIX of 1998. [33] [34]

The law of Hungary includes company law. [35] Legislation on accounting has included Act C of 2000. [36] [37]

The law of Hungary includes energy law. [38] Legislation on electricity has included Act XLVIII of 1994. [39] [40]

The royal prerogatives of the King of Hungary included prefection. [41] Tripartitum was a law book. [42]

The Napoleonic Code, officially the Civil Code of the French, is the French civil code established during the French Consulate in 1804 and still in force in France, although heavily and frequently amended since its inception.

In law, codification is the process of collecting and restating the law of a jurisdiction in certain areas, usually by subject, forming a legal code, i.e. a codex (book) of law.

Abortion laws vary widely among countries and territories, and have changed over time. Such laws range from abortion being freely available on request, to regulation or restrictions of various kinds, to outright prohibition in all circumstances. Many countries and territories that allow abortion have gestational limits for the procedure depending on the reason; with the majority being up to 12 weeks for abortion on request, up to 24 weeks for rape, incest, or socioeconomic reasons, and more for fetal impairment or risk to the woman's health or life. As of 2022, countries that legally allow abortion on request or for socioeconomic reasons comprise about 60% of the world's population. In 2024, France became the first country to explicitly protect abortion rights in its constitution.

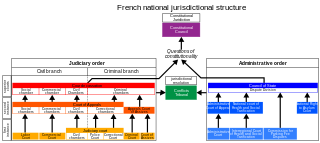

French law has a dual jurisdictional system comprising private law, also known as judicial law, and public law.

The law of Northern Ireland is the legal system of statute and common law operating in Northern Ireland since the partition of Ireland established Northern Ireland as a distinct jurisdiction in 1921. Prior to 1921, Northern Ireland was part of the same legal system as the rest of Ireland.

The Judiciary of the Czech Republic is set out in the Constitution, which defines courts as independent institutions within the constitutional framework of checks and balances.

The law of Gibraltar is a combination of common law and statute, and is based heavily upon English law.

The law of Finland is based on the civil law tradition, consisting mostly of statutory law promulgated by the Parliament of Finland. The constitution of Finland, originally approved in 1919 and rewritten in 2000, has supreme authority and sets the most important procedures for enacting and applying legislation. As in civil law systems in general, judicial decisions are not generally authoritative and there is little judge-made law. Supreme Court decisions can be cited, but they are not actually binding.

The Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation is a ministry of the Government of Russia responsible for the legal system and penal system.

Current Law Statutes Annotated, published between 1994 and 2004 as Current Law Statutes, contains annotated copies of Acts of the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed since 1947 and Acts of the Scottish Parliament passed since 1999. It is published by Sweet & Maxwell in London and by W Green in Edinburgh. It was formerly also published by Stevens & Sons in London.

Czech law, often referred to as the legal order of the Czech Republic, is the system of legal rules in force in the Czech Republic, and in the international community it is a member of. Czech legal system belongs to the Germanic branch of continental legal culture. Major areas of public and private law are divided into branches, among them civil, criminal, administrative, procedural and labour law, and systematically codified.

The administration of justice is the process by which the legal system of a government is executed. The presumed goal of such an administration is to provide justice for all those accessing the legal system.

The law of Albania is civil law.

The law of Luxembourg is civil law. From the Tenth Century to the Fifteenth Century the law of the Grand Duchy was customary law.

The law of Malta incorporates continental law, common law and local traditions, such as Code de Rohan. A municipal code was enacted in 1784 and replaced in 1813. Maltese law has evolved over the centuries and reflected the rule of the context of the time. At present Malta has a mixed-system codification, influenced by Roman law, French Napoleonic Code, British Common Law, European Union law, international law, and customary law established through local customs

The law of Romania is civil law.

The law of the Slovak Republic is civil law.

Armenian law, that being the modern Legal system of Armenia, is a system of law acted in Armenia.

The law of Bolivia includes a constitution and a number of codes.

The law of Peru includes a constitution and legislation. The law of Perú is part of the Roman-Germanic tradition that concedes the utmost importance to the written law, therefore, statutes known as leyes are the primary source of the law.