The Glorious Revolution is the term, first used in 1689, to summarise events leading to the deposition of James II and VII of England, Ireland, and Scotland in November 1688 and his replacement by his daughter Mary II and her husband, who was also James's nephew William III of Orange, de facto ruler of the Dutch Republic. Known as the Glorieuze Overtocht or Glorious Crossing in the Netherlands, it has been described both as the last successful invasion of England and as an internal coup.

The Whigs were a political faction and then a political party in the Parliaments of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. Between the 1680s and the 1850s, the Whigs contested power with their rivals, the Tories. The Whigs merged into the Liberal Party with the Peelites and Radicals in the 1850s. Many Whigs left the Liberal Party in 1886 to form the Liberal Unionist Party, which merged into the Conservative Party in 1912.

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys, PC, also known as "the Hanging Judge", was a Welsh judge. He became notable during the reign of King James II, rising to the position of Lord Chancellor. His conduct as a judge was to enforce royal policy, resulting in a historical reputation for severity and bias.

The Tories were a loosely organised political faction and later a political party, in the Parliaments of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom. They first emerged during the 1679 Exclusion Crisis, when they opposed Whig efforts to exclude James, Duke of York from the succession on the grounds of his Catholicism. Despite their fervent opposition to state-sponsored Catholicism, Tories opposed exclusion in the belief inheritance based on birth was the foundation of a stable society.

Henry Sydney, 1st Earl of Romney was an English Army officer, Whig politician and peer who served as Master-General of the Ordnance from 1693 to 1702. He is best known as one of the Immortal Seven, a group of seven Englishmen who drafted an invitation to William of Orange, which led to the November 1688 Glorious Revolution and subsequent deposition of James II of England.

Sir William Williams, 1st Baronet was a Welsh lawyer and politician. He served as a Member of Parliament for Chester and later Beaumaris, and was appointed Speaker for two English Parliaments during the reign of Charles II. He later served as Solicitor General during the reign of James II. Williams had a bitter personal and professional rivalry with Judge Jeffreys.

John Drummond, 1st Earl of Melfort, styled Duke of Melfort in the Jacobite peerage, was a Scottish politician and close advisor to James II. A Catholic convert, Melfort and his brother the Earl of Perth consistently urged James not to compromise with his opponents, contributing to his increasing isolation and ultimate deposition in the 1688 Glorious Revolution.

Admiral of the Blue George Churchill was an English naval officer, who served as a Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty from 1699 to 1702 and sat on the Lord High Admirals Council from 1702 to 1708. He was Member of Parliament for St Albans from 1685 to 1708, then Portsmouth from 1708 until his death in 1710.

Major General Charles Trelawny, also spelt 'Trelawney', was an English soldier from Cornwall who played a prominent part in the 1688 Glorious Revolution, and was a Member of Parliament for various seats between 1685 and 1713.

Henry Bertie, JP, of Chesterton, Oxfordshire was an English soldier and Tory politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons between 1678 and 1715.

Theophilus Hastings, 7th Earl of Huntingdon was a 17th-century English politician and Jacobite. One of the few non-Catholics to remain loyal to James II of England after November 1688, on the rare occasions he is mentioned by historians, he is described as a 'facile instrument of the Stuarts,' a 'turncoat' or 'outright renegade.'

Robert Leke, 3rd Earl of Scarsdale was an English politician and courtier, styled Lord Deincourt from 1655 to 1681.

The English Convention was an assembly of the Parliament of England which met between 22 January and 12 February 1689 and transferred the crowns of England and Ireland from James II to William III and Mary II.

The Exclusion Bill Parliament was a Parliament of England during the reign of Charles II of England, named after the long saga of the Exclusion Bill. Summoned on 24 July 1679, but prorogued by the king so that it did not assemble until 21 October 1680, it was dissolved three months later on 18 January 1680/81.

Sir John Talbot was an English politician, soldier, and landowner, who was Member of Parliament for various seats between 1660 and 1685. He held rank in a number of regiments, although he does not appear to have seen active service.

The Toleration Act 1688, also referred to as the Act of Toleration, was an Act of the Parliament of England. Passed in the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution, it received royal assent on 24 May 1689.

Lieutenant-General Thomas Windsor, 1st Viscount Windsor, styled The Honourable Thomas Windsor until 1699, was a British Army officer, landowner and Tory politician who sat in the English and British House of Commons between 1685 and 1712. He was then elevated to the British House of Lords as one of Harley's Dozen.

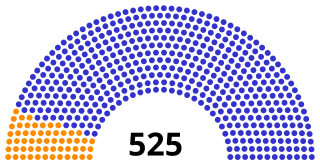

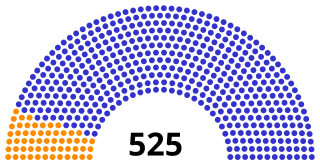

The 1685 English general election elected the only parliament of James II of England, known as the Loyal Parliament. This was the first time the pejorative words Whig and Tory were used as names for political groupings in the Parliament of England. Party strengths are an approximation, with many MPs' allegiances being unknown.

Brigadier-General Richard Leveson, 12 July 1659 to March 1699, was the son of a wealthy merchant from Wolverhampton, who served in the army of James II until the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, when he defected to join William III. He fought in Ireland and Flanders, sat as MP for Lichfield and Newport, and was Governor of Berwick-upon-Tweed from 1691 until his death in March 1699.

Sir Richard Atherton, was a Tory politician and an English Member of Parliament elected in 1671 representing Liverpool. He also served as Mayor of Liverpool from 1684 to 1685. He resided at Bewsey Old Hall, Warrington and died in 1687. He was 11th in descent from Sir William Atherton MP for the same county in 1381 and was the last Atherton in the male line to have been a member of parliament.