Mura is a language of Amazonas, Brazil. It is most famous for Pirahã, its sole surviving dialect. Linguistically, it is typified by agglutinativity, a very small phoneme inventory, whistled speech, and the use of tone.

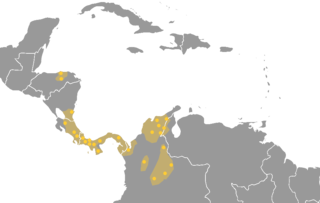

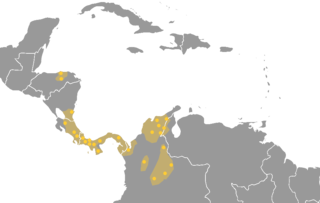

The Chibchan languages make up a language family indigenous to the Isthmo-Colombian Area, which extends from eastern Honduras to northern Colombia and includes populations of these countries as well as Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. The name is derived from the name of an extinct language called Chibcha or Muysccubun, once spoken by the people who lived on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense of which the city of Bogotá was the southern capital at the time of the Spanish Conquista. However, genetic and linguistic data now indicate that the original heart of Chibchan languages and Chibchan-speaking peoples might not have been in Colombia, but in the area of the Costa Rica-Panama border, where the greatest variety of Chibchan languages has been identified.

This is a list of different language classification proposals developed for the indigenous languages of the Americas. The article is divided into North, Central, and South America sections; however, the classifications do not correspond to these divisions.

Barbacoan is a language family spoken in Colombia and Ecuador.

Paezan may be any of several hypothetical or obsolete language-family proposals of Colombia and Ecuador named after the Paez language.

Tacanan is a family of languages spoken in Bolivia, with Ese’ejja also spoken in Peru. It may be related to the Panoan languages. Many of the languages are endangered.

The Waorani (Huaorani) language, commonly known as Sabela is a vulnerable language isolate spoken by the Huaorani people, an indigenous group living in the Amazon rainforest between the Napo and Curaray Rivers in Ecuador. A small number of speakers with so-called uncontacted groups may live in Peru.

The Chicham languages, also known as Jivaroan is a small language family of northern Peru and eastern Ecuador.

Páez is a language of Colombia, spoken by the Páez people. Crevels (2011) estimates 60,000 speakers out of an ethnic population of 140,000.

Yuracaré is an endangered language isolate of central Bolivia in Cochabamba and Beni departments spoken by the Yuracaré people.

Mataguayo–Guaicuru, Mataco–Guaicuru or Macro-Waikurúan is a proposed language family consisting of the Mataguayan and Guaicuruan languages. Pedro Viegas Barros claims to have demonstrated it. These languages are spoken in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia.

Zamucoan is a small language family of Paraguay and Bolivia.

The Piaroa–Saliban, also known as Saliban, are a small proposed language family of the middle Orinoco Basin, which forms an independent island within an area of Venezuela and Colombia dominated by peoples of Carib and Arawakan affiliation.

Vilela is an extinct language last spoken in the Resistencia area of Argentina and in the eastern Chaco near the Paraguayan border. Dialects were Ocol, Chinipi, Sinipi; only Ocol survives. The people call themselves Waqha-umbaβelte 'Waqha speakers'.

The two Lule–Vilela languages constitute a small, distantly related language family of northern Argentina. Kaufman found the relationship likely and with general agreement among the major classifiers of South American languages. Viegas Barros published additional evidence from 1996–2006. However, Zamponi (2008) considers Lule and Vilela each as language isolates, with similarities being due to contact.

Betoi (Betoy) or Betoi-Jirara is an extinct language of Colombia and Venezuela, south of the Apure River near the modern border with Colombia. The names Betoi and Jirara are those of two of its peoples/dialects; the language proper has no known name. At contact, Betoi was a local lingua franca spoken between the Uribante and Sarare rivers and along the Arauca. Enough was recorded for a brief grammatical monograph to be written.

Guamo is an extinct language of Venezuela. Kaufman (1990) finds a connection with the Chapacuran languages convincing.

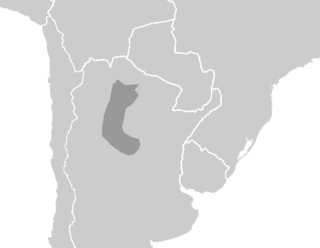

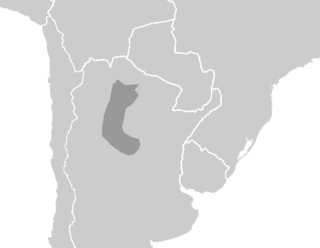

The Lule people, or Lules, are an indigenous people in Argentina. They were originally encountered in the area that is now the Salta Province of Argentina, as well as in nearby areas of modern-day Bolivia and Paraguay. They were later displaced by the Wichí toward the south of Salta Province, the north-east of Santiago del Estero Province, and eastern Tucumán Province. The Lule language is distantly related to the Vilela language, and together they form the Lule-Vilela language family. Today, 3,721 people in Argentina claim Lule ethnic affiliation, according to the 2010 census.

The indigenous languages of South America are those whose origin dates back to the pre-Columbian era. The subcontinent has great linguistic diversity, but, as the number of speakers of indigenous languages is diminishing, it is estimated that it could become one of the least linguistically diverse regions of the planet.