Varicella zoster virus (VZV), also known as human herpesvirus 3 or Human alphaherpesvirus 3 (taxonomically), is one of nine known herpes viruses that can infect humans. It causes chickenpox (varicella) commonly affecting children and young adults, and shingles in adults but rarely in children. As a late complication of VZV infection, Ramsay Hunt syndrome type 2 may develop in rare cases. VZV infections are species-specific to humans. The virus can survive in external environments for a few hours.

Shingles, also known as herpes zoster, is a viral disease characterized by a painful skin rash with blisters in a localized area. Typically the rash occurs in a single, wide mark either on the left or right side of the body or face. Two to four days before the rash occurs there may be tingling or local pain in the area. Other common symptoms are fever, headache, and tiredness. The rash usually heals within two to four weeks; however, some people develop ongoing nerve pain which can last for months or years, a condition called postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). In those with poor immune function the rash may occur widely. If the rash involves the eye, vision loss may occur.

A mohel is a Jewish man trained in the practice of brit milah, the "covenant of male circumcision". Women who are trained in the practice are referred to as a mohelet.

A herpetic whitlow is a herpes lesion (whitlow), typically on a finger or thumb, caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV). Occasionally infection occurs on the toes or on the nail cuticle. Herpes whitlow can be caused by infection by HSV-1 or HSV-2. HSV-1 whitlow is often contracted by health care workers that come in contact with the virus; it is most commonly contracted by dental workers and medical workers exposed to oral secretions. It is also often observed in thumb-sucking children with primary HSV-1 oral infection (autoinoculation) prior to seroconversion, and in adults aged 20 to 30 following contact with HSV-2-infected genitals.

A vertically transmitted infection is an infection caused by pathogenic bacteria or viruses that use mother-to-child transmission, that is, transmission directly from the mother to an embryo, fetus, or baby during pregnancy or childbirth. It can occur when the mother has a pre-existing disease or becomes infected during pregnancy. Nutritional deficiencies may exacerbate the risks of perinatal infections. Vertical transmission is important for the mathematical modelling of infectious diseases, especially for diseases of animals with large litter sizes, as it causes a wave of new infectious individuals.

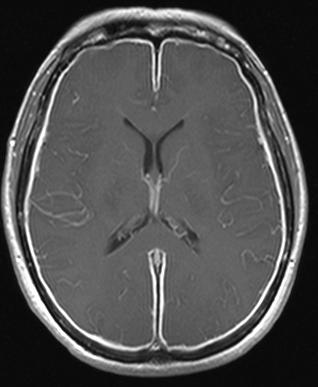

Viral encephalitis is inflammation of the brain parenchyma, called encephalitis, by a virus. The different forms of viral encephalitis are called viral encephalitides. It is the most common type of encephalitis and often occurs with viral meningitis. Encephalitic viruses first cause infection and replicate outside of the central nervous system (CNS), most reaching the CNS through the circulatory system and a minority from nerve endings toward the CNS. Once in the brain, the virus and the host's inflammatory response disrupt neural function, leading to illness and complications, many of which frequently are neurological in nature, such as impaired motor skills and altered behavior.

Gingivostomatitis is a combination of gingivitis and stomatitis, or an inflammation of the oral mucosa and gingiva. Herpetic gingivostomatitis is often the initial presentation during the first ("primary") herpes simplex infection. It is of greater severity than herpes labialis which is often the subsequent presentations. Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis is the most common viral infection of the mouth.

Herpes simplex virus1 and 2, also known by their taxonomic names Human alphaherpesvirus 1 and Human alphaherpesvirus 2, are two members of the human Herpesviridae family, a set of viruses that produce viral infections in the majority of humans. Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 are very common and contagious. They can be spread when an infected person begins shedding the virus.

Genital herpes is a herpes infection of the genitals caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV). Most people either have no or mild symptoms and thus do not know they are infected. When symptoms do occur, they typically include small blisters that break open to form painful ulcers. Flu-like symptoms, such as fever, aching, or swollen lymph nodes, may also occur. Onset is typically around 4 days after exposure with symptoms lasting up to 4 weeks. Once infected further outbreaks may occur but are generally milder.

A genital ulcer is an open sore located on the genital area, which includes the vulva, penis, perianal region, or anus. Genital ulcers are most commonly caused by infectious agents. However, this is not always the case, as a genital ulcer may have noninfectious causes as well.

The central nervous system (CNS) controls most of the functions of the body and mind. It comprises the brain, spinal cord and the nerve fibers that branch off to all parts of the body. The CNS viral diseases are caused by viruses that attack the CNS. Existing and emerging viral CNS infections are major sources of human morbidity and mortality.

Herpes simplex, often known simply as herpes, is a viral infection caused by the herpes simplex virus. Herpes infections are categorized by the area of the body that is infected. The two major types of herpes are oral herpes and genital herpes, though other forms also exist.

Herpes meningitis is inflammation of the meninges, the protective tissues surrounding the spinal cord and brain, due to infection from viruses of the Herpesviridae family - the most common amongst adults is HSV-2. Symptoms are self-limiting over 2 weeks with severe headache, nausea, vomiting, neck-stiffness, and photophobia. Herpes meningitis can cause Mollaret's meningitis, a form of recurrent meningitis. Lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid results demonstrating aseptic meningitis pattern is necessary for diagnosis and polymerase chain reaction is used to detect viral presence. Although symptoms are self-limiting, treatment with antiviral medication may be recommended to prevent progression to Herpes Meningoencephalitis.

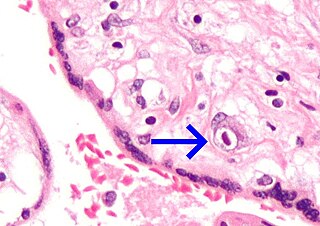

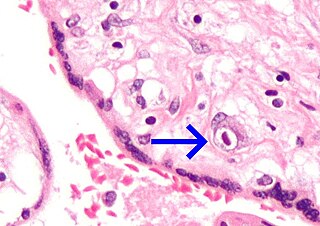

Herpes simplex encephalitis (HSE), or simply herpes encephalitis, is encephalitis due to herpes simplex virus. It is estimated to affect at least 1 in 500,000 individuals per year, and some studies suggest an incidence rate of 5.9 cases per 100,000 live births.

A cold sore is a type of herpes infection caused by the herpes simplex virus that affects primarily the lip. Symptoms typically include a burning pain followed by small blisters or sores. The first attack may also be accompanied by fever, sore throat, and enlarged lymph nodes. The rash usually heals within ten days, but the virus remains dormant in the trigeminal ganglion. The virus may periodically reactivate to create another outbreak of sores in the mouth or lip.

The epidemiology of herpes simplex is of substantial epidemiologic and public health interest. Worldwide, the rate of infection with herpes simplex virus—counting both HSV-1 and HSV-2—is around 90%. Although many people infected with HSV develop labial or genital lesions, the majority are either undiagnosed or display no physical symptoms—individuals with no symptoms are described as asymptomatic or as having subclinical herpes.

Neonatal meningitis is a serious medical condition in infants that is rapidly fatal if untreated. Meningitis, an inflammation of the meninges, the protective membranes of the central nervous system, is more common in the neonatal period than any other time in life, and is an important cause of morbidity and mortality globally. Mortality is roughly half in developing countries and ranges from 8%-12.5% in developed countries.

Herpetic simplex keratitis is a form of keratitis caused by recurrent herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in the cornea.

Pritelivir is a direct-acting antiviral drug in development for the treatment of herpes simplex virus infections (HSV). This is particularly important in immune compromised patients. It is currently in Phase III clinical development by the German biopharmaceutical company AiCuris Anti-infective Cures AG. US FDA granted fast track designation for pritelivir in 2017 and breakthrough therapy designation 2020.

Neonatal infections are infections of the neonate (newborn) acquired during prenatal development or within the first four weeks of life. Neonatal infections may be contracted by mother to child transmission, in the birth canal during childbirth, or after birth. Neonatal infections may present soon after delivery, or take several weeks to show symptoms. Some neonatal infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, and malaria do not become apparent until much later. Signs and symptoms of infection may include respiratory distress, temperature instability, irritability, poor feeding, failure to thrive, persistent crying and skin rashes.