Stormwater, also written storm water, is water that originates from precipitation (storm), including heavy rain and meltwater from hail and snow. Stormwater can soak into the soil (infiltrate) and become groundwater, be stored on depressed land surface in ponds and puddles, evaporate back into the atmosphere, or contribute to surface runoff. Most runoff is conveyed directly as surface water to nearby streams, rivers or other large water bodies without treatment.

Water pollution is the contamination of water bodies, with a negative impact on their uses. It is usually a result of human activities. Water bodies include lakes, rivers, oceans, aquifers, reservoirs and groundwater. Water pollution results when contaminants mix with these water bodies. Contaminants can come from one of four main sources. These are sewage discharges, industrial activities, agricultural activities, and urban runoff including stormwater. Water pollution may affect either surface water or groundwater. This form of pollution can lead to many problems. One is the degradation of aquatic ecosystems. Another is spreading water-borne diseases when people use polluted water for drinking or irrigation. Water pollution also reduces the ecosystem services such as drinking water provided by the water resource.

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the primary federal law in the United States governing water pollution. Its objective is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters; recognizing the responsibilities of the states in addressing pollution and providing assistance to states to do so, including funding for publicly owned treatment works for the improvement of wastewater treatment; and maintaining the integrity of wetlands.

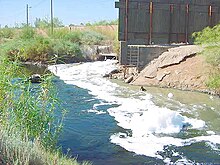

The Tijuana River is an intermittent river, 120 mi (195 km) long, near the Pacific coast of northern Baja California state in northwestern Mexico and Southern California in the western United States. The river is heavily polluted with raw sewage from the city of Tijuana, Mexico.

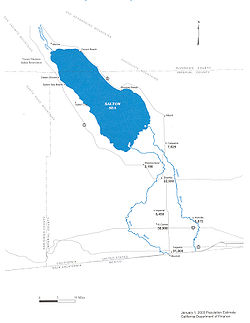

The All-American Canal is an 82-mile-long (132 km) aqueduct, located in southeastern California. It conveys water from the Colorado River into the Yuma Project, the Imperial Valley, and to nine cities. It is the Imperial Valley's only water source, and replaced the Alamo Canal, which was located mostly in Mexico. The Imperial Dam, about 30 miles (48 km) northeast of Yuma, Arizona, on the Colorado River, diverts water into the All-American Canal, which runs to just west of Calexico, California, before its last branch heads mostly north into the Imperial Valley. Smaller canals branching off the All-American Canal move water into the Yuma Valley and the Imperial Valley. These canal systems irrigate up to 630,000 acres (250,000 ha) of crop land and have made possible a greatly increased crop yield in this area, originally one of the driest on earth. It is the largest irrigation canal in the world, carrying a maximum of 26,155 cubic feet per second (740.6 m3/s). Agricultural runoff from the All-American Canal drains into the Salton Sea.

Sewage disposal regulation and administration describes the governance of sewage treatment and disposal.

Agricultural wastewater treatment is a farm management agenda for controlling pollution from confined animal operations and from surface runoff that may be contaminated by chemicals in fertilizer, pesticides, animal slurry, crop residues or irrigation water. Agricultural wastewater treatment is required for continuous confined animal operations like milk and egg production. It may be performed in plants using mechanized treatment units similar to those used for industrial wastewater. Where land is available for ponds, settling basins and facultative lagoons may have lower operational costs for seasonal use conditions from breeding or harvest cycles. Animal slurries are usually treated by containment in anaerobic lagoons before disposal by spray or trickle application to grassland. Constructed wetlands are sometimes used to facilitate treatment of animal wastes.

A combined sewer is a type of gravity sewer with a system of pipes, tunnels, pump stations etc. to transport sewage and urban runoff together to a sewage treatment plant or disposal site. This means that during rain events, the sewage gets diluted, resulting in higher flowrates at the treatment site. Uncontaminated stormwater simply dilutes sewage, but runoff may dissolve or suspend virtually anything it contacts on roofs, streets, and storage yards. As rainfall travels over roofs and the ground, it may pick up various contaminants including soil particles and other sediment, heavy metals, organic compounds, animal waste, and oil and grease. Combined sewers may also receive dry weather drainage from landscape irrigation, construction dewatering, and washing buildings and sidewalks.

Nonpoint source (NPS) pollution refers to diffuse contamination of water or air that does not originate from a single discrete source. This type of pollution is often the cumulative effect of small amounts of contaminants gathered from a large area. It is in contrast to point source pollution which results from a single source. Nonpoint source pollution generally results from land runoff, precipitation, atmospheric deposition, drainage, seepage, or hydrological modification where tracing pollution back to a single source is difficult. Nonpoint source water pollution affects a water body from sources such as polluted runoff from agricultural areas draining into a river, or wind-borne debris blowing out to sea. Nonpoint source air pollution affects air quality, from sources such as smokestacks or car tailpipes. Although these pollutants have originated from a point source, the long-range transport ability and multiple sources of the pollutant make it a nonpoint source of pollution; if the discharges were to occur to a body of water or into the atmosphere at a single location, the pollution would be single-point.

Best management practices (BMPs) is a term used in the United States and Canada to describe a type of water pollution control. Historically the term has referred to auxiliary pollution controls in the fields of industrial wastewater control and municipal sewage control, while in stormwater management and wetland management, BMPs may refer to a principal control or treatment technique as well.

Water supply and sanitation in the United States involves a number of issues including water scarcity, pollution, a backlog of investment, concerns about the affordability of water for the poorest, and a rapidly retiring workforce. Increased variability and intensity of rainfall as a result of climate change is expected to produce both more severe droughts and flooding, with potentially serious consequences for water supply and for pollution from combined sewer overflows. Droughts are likely to particularly affect the 66 percent of Americans whose communities depend on surface water. As for drinking water quality, there are concerns about disinfection by-products, lead, perchlorates, PFAS and pharmaceutical substances, but generally drinking water quality in the U.S. is good.

Sewage treatment is a type of wastewater treatment which aims to remove contaminants from sewage to produce an effluent that is suitable to discharge to the surrounding environment or an intended reuse application, thereby preventing water pollution from raw sewage discharges. Sewage contains wastewater from households and businesses and possibly pre-treated industrial wastewater. There are a high number of sewage treatment processes to choose from. These can range from decentralized systems to large centralized systems involving a network of pipes and pump stations which convey the sewage to a treatment plant. For cities that have a combined sewer, the sewers will also carry urban runoff (stormwater) to the sewage treatment plant. Sewage treatment often involves two main stages, called primary and secondary treatment, while advanced treatment also incorporates a tertiary treatment stage with polishing processes and nutrient removal. Secondary treatment can reduce organic matter from sewage, using aerobic or anaerobic biological processes. A so-called quarternary treatment step can also be added for the removal of organic micropollutants, such as pharmaceuticals. This has been implemented in full-scale for example in Sweden.

The Hardy River is a 26-kilometer (16 mi)-long Mexican river formed by residual agricultural waters from the Mexicali Valley, and running into the Colorado River. The river is believed to have been an ancient channel of the Colorado, as well as the primary outflow for the prehistoric Lake Cahuilla.

Nutrient pollution, a form of water pollution, refers to contamination by excessive inputs of nutrients. It is a primary cause of eutrophication of surface waters, in which excess nutrients, usually nitrogen or phosphorus, stimulate algal growth. Sources of nutrient pollution include surface runoff from farm fields and pastures, discharges from septic tanks and feedlots, and emissions from combustion. Raw sewage is a large contributor to cultural eutrophication since sewage is high in nutrients. Releasing raw sewage into a large water body is referred to as sewage dumping, and still occurs all over the world. Excess reactive nitrogen compounds in the environment are associated with many large-scale environmental concerns. These include eutrophication of surface waters, harmful algal blooms, hypoxia, acid rain, nitrogen saturation in forests, and climate change.

Allegheny County Sanitary Authority is a municipal authority in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania that provides wastewater treatment services to 83 communities, including the city of Pittsburgh. Its principal sewage treatment plant is along the Ohio River downstream from Pittsburgh.

Water pollution in the United States is a growing problem that became critical in the 19th century with the development of mechanized agriculture, mining, and manufacturing industries—although laws and regulations introduced in the late 20th century have improved water quality in many water bodies. Extensive industrialization and rapid urban growth exacerbated water pollution as a lack of regulation allowed for discharges of sewage, toxic chemicals, nutrients, and other pollutants into surface water. This has led to the need for more improvement in water quality as it is still threatened and not fully safe.

Point source water pollution comes from discrete conveyances and alters the chemical, biological, and physical characteristics of water. In the United States, it is largely regulated by the Clean Water Act (CWA). Among other things, the Act requires dischargers to obtain a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit to legally discharge pollutants into a water body. However, point source pollution remains an issue in some water bodies, due to some limitations of the Act. Consequently, other regulatory approaches have emerged, such as water quality trading and voluntary community-level efforts.

The International Wastewater Treatment Plant (IWTP) was developed by the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC) in the South Bay area of San Diego, California. Construction began on a 75-acre site (30 ha), west of San Ysidro in the Tijuana River Valley. The project, authorized by the U.S. Congress in 1989 and formally agreed between the two countries in July 1990, was part of a regional approach to solve long-standing problems, particularly the flow of sewage-contaminated water into the ocean via the Tijuana River.

Water pollution in Canada is generally local and regional in water-rich Canada, and most Canadians have "access to sufficient, affordable, and safe drinking water and adequate sanitation." Water pollution in Canada is caused by municipal sewage, urban runoff, industrial pollution and industrial waste, agricultural pollution, inadequate water infrastructure. This is a long-term threat in Canada due to "population growth, economic development, climate change, and scarce fresh water supplies in certain parts of the country."