Władysław III of Poland, also known as Ladislaus of Varna, was King of Poland and Supreme Duke of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from 1434 as well as King of Hungary and Croatia from 1440 until his death at the Battle of Varna. He was the eldest son of Władysław II Jagiełło (Jogaila) and the Lithuanian noblewoman Sophia of Halshany.

Jogaila, later Władysław II Jagiełło, was Grand Duke of Lithuania, later giving the position to his cousin Vytautas in exchange for the title of Supreme Duke of Lithuania (1401–1434) and then King of Poland (1386–1434), first alongside his wife Jadwiga until 1399, and then sole ruler of Poland. Raised a Lithuanian polytheist, he converted to Catholicism in 1386 and was baptized as Ladislaus in Kraków, married the young Queen Jadwiga, and was crowned King of Poland as Władysław II Jagiełło. In 1387, he converted Lithuania to Catholicism. His own reign in Poland started in 1399, upon the death of Queen Jadwiga, lasted a further thirty-five years, and laid the foundation for the centuries-long Polish–Lithuanian union. He was a member of the Jagiellonian dynasty in Poland that bears his name and was previously also known as the Gediminid dynasty in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The dynasty ruled both states until 1572, and became one of the most influential dynasties in late medieval and early modern Europe.

In World War II, the Polish armed forces were the fourth largest Allied forces in Europe, after those of the Soviet Union, United States, and Britain.[a] Poles made substantial contributions to the Allied effort throughout the war, fighting on land, sea, and in the air.

Władysław Albert Anders was a general in the Polish Army and later in life a politician and prominent member of the Polish government-in-exile in London.

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile, was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and the Slovak Republic, which brought to an end the Second Polish Republic.

Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, in English known as Adam George Czartoryski, was a Polish nobleman, statesman, diplomat and author.

Tadeusz Józef Sulimirski was a Polish-born British historian and archaeologist, who emigrated to the United Kingdom soon after the outbreak of World War II in 1939. Sulimirski was a pioneer and leading expert in the study of the archaeology of steppe nomads, particularly the Cimmerians, Scythians and Sarmatians.

The Wawel Royal Castle and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established on the orders of King Casimir III the Great and enlarged over the centuries into a number of structures around an Italian-styled courtyard. It represents nearly all European architectural styles of the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods.

The Konarski Secondary School is a coeducational public secondary school in Rzeszów, Poland. Founded in 1658, it is one of the oldest secondary schools in Poland. Located in the old town in a historic building designed by Tylman van Gameren, it plays an important role in the cultural life of Rzeszów and Subcarpathia Province.

British Poles, alternatively known as Polish British people or Polish Britons, are ethnic Poles who are citizens of the United Kingdom. The term includes people born in the UK who are of Polish descent and Polish-born people who reside in the UK. There are approximately 682,000 people born in Poland residing in the UK. Since the late 20th century, they have become one of the largest ethnic minorities in the country alongside Irish, Indians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Germans, and Chinese. The Polish language is the second-most spoken language in England and the third-most spoken in the UK after English and Welsh. About 1% of the UK population speaks Polish. The Polish population in the UK has increased more than tenfold since 2001.

The Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum, known as Sikorski Institute, named after General Władysław Sikorski, is a leading London-based museum and archive for research into Poland during World War II and the Polish diaspora. It is a non-governmental organisation managed by scholars from the Polish community in the United Kingdom, housed at 20 Prince's Gate in West London, in a Grade II listed terrace on Kensington Road facing Hyde Park. It is incidentally part of the same Victorian development by Charles James Freake as the nearby Polish Hearth Club. Although the institute is closer to the commercial centres of Kensington, it is just within the City of Westminster. In 1988 it merged with the formerly independent Polish Underground Movement (1939–1945) Study Trust –.

Jerzy Władysław Giedroyc was a Polish writer, lawyer, publicist and political activist. For many years, he worked as editor of the highly influential Paris-based periodical, Kultura.

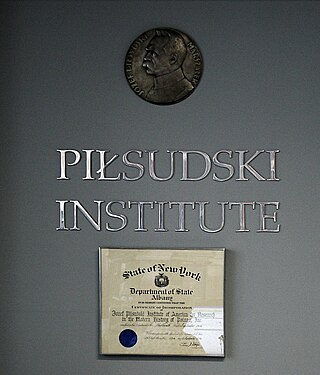

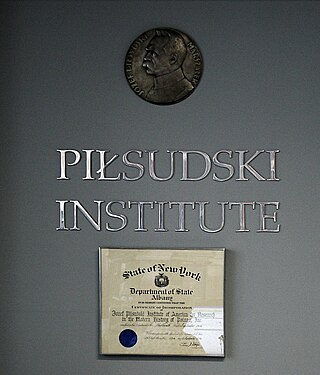

The Józef Piłsudski Institute of America is a museum and research center devoted to the study of modern Polish history and named after the Polish interwar statesman Józef Piłsudski located in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

The Polish Social and Cultural Centre is a Polish cultural centre in west London, England. It was founded in 1967 and funded by public subscription, on the initiative of Polish engineer Roman Wajda, at 238–246 King Street, Hammersmith.

The Jagiellonian or Jagellonian dynasty, otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty, the House of Jagiellon, or simply the Jagiellons, was the name assumed by a cadet branch of the Lithuanian ducal dynasty of Gediminids upon reception by Jogaila, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, of baptism as Władysław in 1386, which paved the way to his ensuing marriage to the Queen Regnant Jadwiga of Poland, resulting in his ascension to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland as Władysław II Jagiełło, and the effective promotion of his branch to a royal dynasty. The Jagiellons were polyglots and per historical evidence Casimir IV Jagiellon and his son Saint Casimir possibly were the last Jagiellons who spoke in their patrilineal ancestors Lithuanian language, however even the last patrilineal Jagiellonian monarch Sigismund II Augustus maintained two separate and equally lavish Lithuanian-speaking and Polish-speaking royal courts in Lithuania's capital Vilnius. The Jagiellons reigned in several European countries between the 14th and 16th centuries. Members of the dynasty were Kings of Poland (1386–1572), Grand Dukes of Lithuania, Kings of Hungary, and Kings of Bohemia and imperial electors (1471–1526).

Jerzy Tabeau, an imprisoned Polish medical student, was one of the first escapees from Auschwitz to give a detailed report to the outside world on the genocide occurring there. First reports in early 1942 had been made by the Polish officer Witold Pilecki. Zabłotów-born Tabeau's report was known as that of the "Polish major" in the Auschwitz Protocols. After the war, he became a noted cardiologist in Kraków.

The Polish School of Medicine at the University of Edinburgh was established in March 1941. Initially, the idea was to meet the needs of the Polish Armed Forces for doctors but from the outstart, civilian students were admitted. Founded on the basis of an agreement between the Polish Government in Exile and the Senate of The University of Edinburgh this unique wartime initiative enabled students to complete their medical degrees.

Jerzy Sławomir Kulczycki was a Polish engineer, activist bookseller, and publisher. He was the founder in 1996 of the Kulczycki prize in Polish Studies.