William James Dixon was an American blues musician, vocalist, songwriter, arranger and record producer. He was proficient in playing both the upright bass and the guitar, and sang with a distinctive voice, but he is perhaps best known as one of the most prolific songwriters of his time. Next to Muddy Waters, Dixon is recognized as the most influential person in shaping the post–World War II sound of the Chicago blues.

In livestock agriculture and the meat industry, a slaughterhouse, also called an abattoir, is a facility where livestock animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a meat-packing facility.

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

Gary Lawrence Francione is an American academic in the fields of law and philosophy. He is Board of Governors Professor of Law and Katzenbach Scholar of Law and Philosophy at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He is also a visiting professor of philosophy at the University of Lincoln (UK) and honorary professor of philosophy at the University of East Anglia (UK). He is the author of numerous books and articles on animal ethics.

Dehumanization is the denial of full humanity in others along with the cruelty and suffering that accompany it. A practical definition refers to it as the viewing and the treatment of other people as though they lack the mental capacities that are commonly attributed to humans. In this definition, every act or thought that regards a person as "less than" human is dehumanization.

Garfield Bromley Oxnam was a social reformer and American Bishop in the Methodist Episcopal Church, elected in 1936.

Americanization is the process of an immigrant to the United States becoming a person who shares American culture, values, beliefs, and customs by assimilating into the American nation. This process typically involves learning the American English language and adjusting to American culture, values, and customs. It can be considered another form of, or an American subset of Anglicization.

Franklyn MacCormack was an American radio personality in Chicago, Illinois, from the 1930s into the 1970s. After his death, Ward Quaal, the president of the last company for which MacCormack worked, described him as "a natural talent and one of the truly great performers of broadcasting's first 50 years."

"Wang Dang Doodle" is a blues song written by Willie Dixon. Music critic Mike Rowe calls it a party song in an urban style with its massive, rolling, exciting beat. It was first recorded by Howlin' Wolf in 1960 and released by Chess Records in 1961. In 1965, Dixon and Leonard Chess persuaded Koko Taylor to record it for Checker Records, a Chess subsidiary. Taylor's rendition quickly became a hit, reaching number thirteen on the Billboard R&B chart and number 58 on the pop chart. "Wang Dang Doodle" became a blues standard and has been recorded by various artists. Taylor's version was added to the United States National Recording Registry in 2023.

Plant rights are rights to which certain plants may be entitled. Such issues are often raised in connection with discussions about human rights, animal rights, biocentrism, or sentientism.

Norm Phelps was an American animal rights activist, vegetarian and writer. He was a founding member of the Society of Ethical and Religious Vegetarians (SERV), and a former outreach director of the Fund for Animals. He authored four books on animal rights: The Dominion of Love: Animal Rights According to the Bible (2002), The Great Compassion: Buddhism and Animal Rights (2004), The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to PETA (2007), and Changing the Game: Animal Liberation in the Twenty-first Century (2015).

Alice Morgan Wright was an American sculptor, suffragist, and animal welfare activist. She was one of the first American artists to embrace Cubism and Futurism.

The relationship between Christianity and animal rights is complex, with different Christian communities coming to different conclusions about the status of animals. The topic is closely related to, but broader than, the practices of Christian vegetarians and the various Christian environmentalist movements.

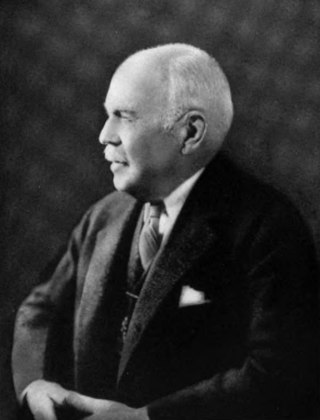

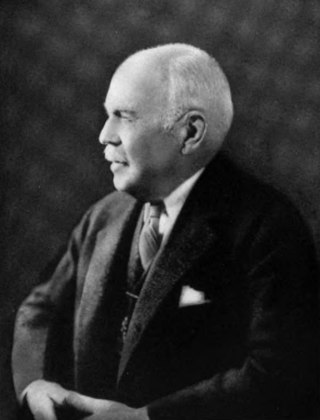

John Howard Moore was an American zoologist, philosopher, educator, and social reformer. He was best known for his advocacy of ethical vegetarianism and his pioneering role in the animal rights movement, both deeply influenced by his ethical interpretation of Darwin's theory of evolution. Moore's most influential work, The Universal Kinship (1906), introduced a sentiocentric philosophy he called the doctrine of Universal Kinship, arguing that the ethical treatment of animals, rooted in the Golden Rule, is essential for human ethical evolution, urging humans to extend their moral considerations to all sentient beings, based on their shared physical and mental evolutionary kinship.

Humphrey Primatt was an English clergyman and early animal rights writer. Primatt has been described as "one of the most important figures in the development of a notion of animal rights."

Francis Harold Rowley was an American Baptist minister, animal welfare campaigner and hymn writer.

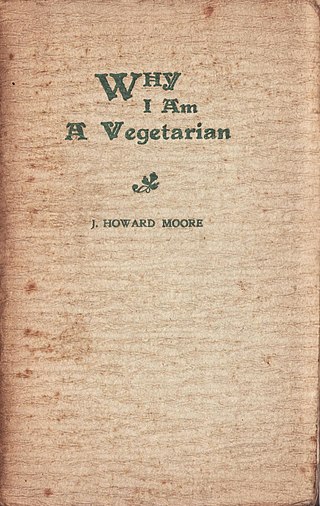

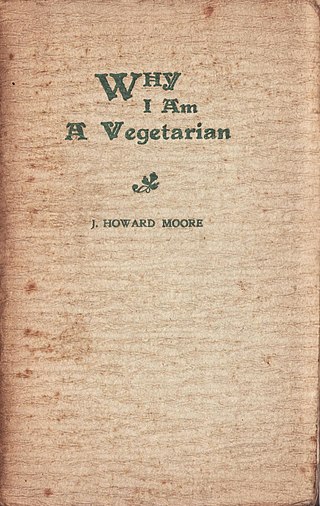

Why I Am a Vegetarian is an 1895 pamphlet based on an address delivered by J. Howard Moore before the Chicago Vegetarian Society. It was reprinted several times by the society and other publishers.

Moral Inquiries on the Situation of Man and of Brutes is an 1824 book by Lewis Gompertz, an early animal rights advocate and vegan. The book argues that animals, like humans, are sentient beings capable of experiencing pain and pleasure, and thus deserve moral consideration. He critiques the exploitation of animals for labour, food, and clothing, condemning practices such as slaughter, hunting, and scientific experimentation. He also addresses the suffering of wild animals, suggesting that even in nature, animals face hardships such as hunger and predation.

The New Ethics is a 1907 book by the American zoologist and philosopher J. Howard Moore, in which he advocates for a form of ethics, that he calls the New Ethics, which applies the principle of the Golden Rule—treat others as you would want to be treated yourself—to all sentient beings. It builds upon the arguments made in his 1899 book, Better-World Philosophy, and 1906 book, The Universal Kinship.

Moral circle expansion is an increase over time in the number and type of entities given moral consideration. The general idea of moral inclusion was discussed by ancient philosophers and since the 19th century has inspired social movements related to human rights and animal rights. Especially in relation to animal rights, the philosopher Peter Singer has written about the subject since the 1970s, and since 2017 so has the think tank Sentience Institute, part of the 21st-century effective altruism movement. There is significant debate on whether humanity actually has an expanding moral circle, considering topics such as the lack of a uniform border of growing moral consideration and the disconnect between people's moral attitudes and their behavior. Research into the phenomenon is ongoing.