Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥākim, better known with his regnal name al-Ẓāhir li-Iʿzāz Dīn Allāh, was the seventh caliph of the Fatimid dynasty (1021–1036). Al-Zahir assumed the caliphate after the disappearance of his father al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah.

Sitt al-Mulk was a Fatimid princess. After the disappearance of her half-brother, the caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, in 1021, she was instrumental in securing the succession of her nephew Ali az-Zahir, and acted as the de facto ruler of the state until her death on 5 February 1023.

The Tayy, , also known as Ṭayyi, Tayyaye, or Taiyaye, are a large and ancient Arab tribe, among whose descendants today are the tribes of Bani Sakher and Shammar. The nisba (patronymic) of Tayy is aṭ-Ṭāʾī (ٱلطَّائِي). In the second century CE, they migrated to the northern Arabian ranges of the Shammar and Salma Mountains, which then collectively became known as the Jabal Tayy, and later Jabal Shammar. The latter continues to be the traditional homeland of the tribe until the present day. They later established relations with the Sasanian and Byzantine empires.

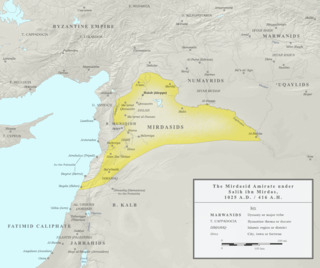

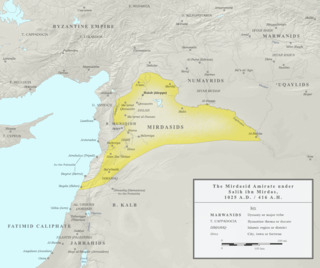

Abu Ali Salih ibn Mirdas, also known by his laqabAsad al-Dawla, was the founder of the Mirdasid dynasty and emir of Aleppo from 1025 until his death in May 1029. At its peak, his emirate (principality) encompassed much of the western Jazira, northern Syria and several central Syrian towns. With occasional interruption, Salih's descendants ruled Aleppo for the next five decades.

Abu Kamil Nasr ibn Salih ibn Mirdas, also known by his laqab of Shibl al-Dawla, was the second Mirdasid emir of Aleppo, ruling between May 1029 until his death. He was the eldest son of Salih ibn Mirdas, founder of the Mirdasid dynasty. Nasr fought alongside his father in the Battle of al-Uqhuwana near Tiberias in 1029, where Salih was killed by a Fatimid army led by Anushtakin al-Dizbari. Afterward, Nasr ruled the emirate jointly with his brother Thimal. The young emirs soon after faced a large-scale Byzantine offensive led by Emperor Romanos III. Commanding a much smaller force of Bedouin horsemen, Nasr routed the Byzantines at the Battle of Azaz in 1030.

The Mirdasid dynasty, also called the Banu Mirdas, was an Arab Shia Muslim dynasty which ruled an Aleppo-based emirate in northern Syria and the western Jazira more or less continuously from 1024 until 1080.

The 1020s was a decade of the Julian Calendar which began on January 1, 1020, and ended on December 31, 1029.

The Battle of Azaz was an engagement fought in August 1030 near the Syrian town of Azaz between the Byzantine army, led by Emperor Romanos III Argyros in person, and the forces of the Mirdasid Emirate of Aleppo, likewise under the personal command of Emir Shibl al-Dawla Nasr. The Mirdasids defeated the much larger Byzantine army and took great booty, even though they were eventually unable to capitalise on their victory.

Mufarrij ibn Daghfal ibn al-Jarrah al-Tayyi, in some sources erroneously called Daghfal ibn Mufarrij, was an emir of the Jarrahid family and leader of the Tayy tribe. Mufarrij was engaged in repeated rebellions against the Fatimid Caliphate, which controlled southern Syria at the time. Although he was several times defeated and forced into exile, by the 990s Mufarrij managed to establish himself and his tribe as the de facto autonomous masters of much of Palestine around Ramlah with Fatimid acquiescence. In 1011, another rebellion against Fatimid authority was more successful, and a short-lived Jarrahid-led Bedouin state was established in Palestine centred at Ramlah. The Bedouin even proclaimed a rival Caliph to the Fatimid al-Hakim, in the person of the Alid Abu'l-Futuh al-Hasan ibn Ja'far. Bedouin independence survived until 1013, when the Fatimids launched their counterattack. Their will to resist weakened by Fatimid bribes, the Bedouin were quickly defeated. At the same time Mufarrij died, possibly poisoned, and his sons quickly came to terms with the Fatimids. Among them, Hassan ibn Mufarrij al-Jarrah managed to succeed to his father's position, and became a major player in the politics of the region over the next decades.

Abu'l-Qasim al-Husayn ibn Ali al-Maghribi, also called al-wazir al-Maghribi and by the surname al-Kamil Dhu'l-Wizaratayn, was the last member of the Banu'l-Maghribi, a family of statesmen who served in several Muslim courts of the Middle East in the 10th and early 11th centuries. Abu'l-Qasim himself was born in Hamdanid Aleppo before fleeing with his father to Fatimid Egypt, where he entered the bureaucracy. After his father's execution, he fled to Palestine, where he raised the local Bedouin leader Mufarrij ibn Daghfal to rebellion against the Fatimids (1011–13). As the rebellion began to falter, he fled to Iraq, where he entered the service of the Buyid emirs of Baghdad. Soon after he moved to the Jazira, where he entered the service of the Uqaylids of Mosul and finally the Marwanids of Mayyafariqin. He was also a poet and author of a number of treatises, including a "mirror for princes".

Nāṣir al-Dawla Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn al-Ḥasan, better known by his honorific epithet as Nasir al-Dawla Ibn Hamdan, was a descendant of the Hamdanid dynasty who became a general of the Fatimid Caliphate, ruing Egypt as a de facto dictator in 1071–1073.

The Jarrahids were an Arab dynasty that intermittently ruled Palestine and controlled Transjordan and northern Arabia in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. They were the ruling family of the Tayy tribe, one of the three powerful tribes of Syria at the time; the other two were Kalb and Kilab.

Hazim ibn Ali ibn Mufarrij ibn Daghfal ibn al-Jarrah al-Ta'i was a chieftain of the Jarrahids, a Bedouin clan of the Banu Tayy tribe that intermittently controlled Palestine, Balqa and northern Arabia in the late 10th and early 11th century. The dynasty remained influential in the northern Arabian Desert in later centuries. Hazim was the son of Ali ibn Mufarrij, and grandson of Mufarrij ibn Daghfal, a former governor of Palestine under the Fatimid Caliphate. There is scant information about Hazim in medieval sources.

Sharaf al-Maʿālī Abu Manṣūr Anūshtakīn al-Dizbarī was a Fatimid statesman and general who became the most powerful Fatimid governor of Syria. Under his Damascus-based administration, all of Syria was united under a single Fatimid authority. Near-contemporary historians, including Ibn al-Qalanisi of Damascus and Ibn al-Adim of Aleppo, noted Anushtakin's wealth, just rule and fair treatment of the population, with whom he was popular.

Rāfiʿ ibn Abīʾl-Layl ibn ʿUlayyān al-Kalbī, also known by his laqabʿIzz al-Dawla, was the emir of the Kalb tribe of Syria in the mid-11th century.

Abu Nasr Fath al-Qal'i, also known by his laqab of Mubarak al-Dawla wa-Sa'id-ha, was the governor of the Citadel of Aleppo during the reign of Emir Mansur ibn Lu'lu'. In 1016, he rebelled against Mansur, in likely collusion with Salih ibn Mirdas, forcing Mansur to flee. After a few months, Fath relinquished control of Aleppo to the Fatimid Caliphate, marking the beginning of direct Fatimid rule over the city. Afterward, he held posts in Tyre, then Jerusalem. As governor of Jerusalem, Fath helped the Fatimid general Anushtakin al-Dizbari suppress a rebellion by the Jarrahids in 1024–1025 and maintained order between the Rabbinate and Karaite Jewish sects during the Hoshana Rabbah festivals at the Mount of Olives in 1029 and 1030.

Quṭb al-Dawla Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Jaʾfar ibn Fallāh was a Fatimid commander and governor in the service of Caliph al-Hakim.

Sinān ibn ʿUlayyān or Sinān ibn al-Bannā, also known by his laqabṢamṣām al-Dawla, was a preeminent emir of the Banu Kalb tribe in Syria under early Fatimid rule. He was an ally of the Fatimids in several campaigns, until rebelling against them in alliance with the chiefs of the Arab tribes of Tayy and Kilab in 1025. Sinan attempted to take over Damascus from its Fatimid ruler, but died in 1028. His nephew Rafi ibn Abi'l-Layl reverted to allying with the Fatimids against the Tayy and Kilab.

Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥasan ibn Ṣāliḥ al-Rūdhabārī, also known by his title ʿAmid al-Dawla, was the vizier of the Fatimid Caliphate in 1024–1027, during the reign of Caliph al-Zahir.

The Battle of al-Uqhuwana was fought at a place east of Lake Tiberias in May 1029 between the Fatimid Caliphate under general Anushtakin al-Dizbari and a coalition of Syrian Bedouin tribes.