There are many Roman sites in Great Britain that are open to the public. There are also many sites that do not require special access, including Roman roads, and sites that have not been uncovered.

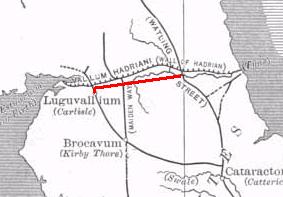

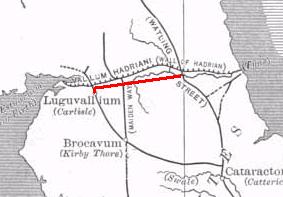

The Stanegate was an important Roman road and early frontier built in what is now northern England. It linked many forts including two that guarded important river crossings: Corstopitum (Corbridge) on the River Tyne in the east and Luguvalium (Carlisle) in the west. The Stanegate ran through the natural gap formed by the valleys of the River Tyne in Northumberland and the River Irthing in Cumbria. It predated the Hadrian's Wall frontier by several decades; the Wall would later follow a similar route, albeit slightly to the north.

The River Irthing is a river in Cumbria, England and a major tributary of the River Eden. The name is recorded as Ard or Arden in early references. For the first 15 miles of its course it defines the border between Northumberland and Cumbria.

Housesteads Roman Fort was an auxiliary fort on Hadrian's Wall, at Housesteads, Northumberland, England. It is dramatically positioned on the end of the mile-long crag of the Whin Sill over which the Wall runs, overlooking sparsely populated hills. It was called the "grandest station" on the Wall and is one of the best-preserved and extensively displayed forts. It was occupied for almost 300 years. It was located 5.3 miles west from Carrawburgh fort, 6 miles east of Great Chesters fort and about two miles north east of the existing fort at Vindolanda on the Stanegate road.

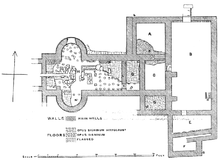

Segedunum was a Roman fort at modern-day Wallsend, North Tyneside in North East England. The fort lay at the eastern end of Hadrian's Wall near the banks of the River Tyne. It was in use for approximately 300 years from around 122 AD to almost 400. Today Segedunum is the most thoroughly excavated fort along Hadrian's Wall, and is operated as Segedunum Roman Fort, Baths and Museum. It forms part of the Hadrian's Wall UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Milecastle 48 (Poltross Burn), is a milecastle on Hadrian's Wall (grid reference NY6340666195). Its remains lie near the village of Gilsland in Cumbria where it was historically known as "The King's Stables", owing to the well-preserved interior walls. Unusually a substantial section of stone stairs has survived within the milecastle. The two turrets associated with this milecastle have also survived as above-ground masonry.

Luguvalium was an ancient Roman city in northern Britain located within present-day Carlisle, Cumbria, and may have been the capital of the 4th-century province of Valentia. It was the northernmost city of the Roman Empire.

Cilurnum or Cilurvum was an ancient Roman fort on Hadrian's Wall at Chesters near the village of Walwick, Northumberland. It is also known as Walwick Chesters to distinguish it from Great Chesters fort and Halton Chesters.

Carrawburgh is a settlement in Northumberland. In Roman times, it was the site of a 3+1⁄2-acre (1.5 ha) auxiliary fort on Hadrian's Wall called Brocolitia, Procolita, or Brocolita.

Vindobala was a Roman fort with the modern name, and in the hamlet of, Rudchester, Northumberland. It was the fourth fort on Hadrian's Wall, and situated about 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) to the west of Condercum (Benwell) fort and 7.5 miles east of Halton Chesters fort. The site of the fort is bisected by the B6318 Military Road, which runs along the route of the wall at that point.

Hunnum was a Roman fort on Hadrian's Wall located north of the modern-day village of Halton, Northumberland in North East England. It was the fifth fort on Hadrian's Wall and is situated about 7.5 miles west of Vindobala fort, 5.9 miles east of Chesters fort and 2.5 miles north of the Stanegate fort of Coria (Corbridge). The site of the fort is bisected by the B6318 Military Road, which runs along the route of the wall at that point.

The Rudge Cup is a small enamelled bronze cup found in 1725 at Rudge, near Froxfield, in Wiltshire, England. The cup was found down a well on the site of a Roman villa. It is important in that it lists five of the forts on the western section of Hadrian's Wall, thus aiding scholars in identifying the forts correctly. The information on the cup has been compared with the two major sources of information regarding forts on the Wall, the Notitia Dignitatum and the Ravenna Cosmography.

Hadrian's Wall is a former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Britannia, begun in AD 122 in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian. Running from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west of what is now northern England, it was a stone wall with large ditches in front of it and behind it that crossed the whole width of the island. Soldiers were garrisoned along the line of the wall in large forts, smaller milecastles, and intervening turrets. In addition to the wall's defensive military role, its gates may have been customs posts.

The Vacomagi were a people of ancient Britain, known only from a single mention of them by the geographer Claudius Ptolemy. Their principal places are known from Ptolemy's map c.150 of Albion island of Britannia – from the First Map of Europe.

The Military Way is the modern name given to a Roman road constructed immediately to the south of Hadrian's Wall.

Milecastle 19 (Matfen Piers) was a milecastle of the Roman Hadrian's Wall. Sited just to the east of the hamlet of Matfen Piers, the milecastle is today covered by the B6318 Military Road. The milecastle is notable for the discovery of an altar by Eric Birley in the 1930s. An inscription on the altar is one of the few dedications to a mother goddess found in Roman Britain, and was made by members of the First Cohort of Varduli from northern Spain. The presence of the Vardulians at this milecastle has led to debate amongst archaeologists over the origins of troops used to garrison the wall. A smaller altar was found at one of the two associated turrets.

Milecastle 29 (Tower Tye) was a milecastle of the Roman Hadrian's Wall. Its remains exist as a mutilated earth platform accentuated by deep robber-trenches around all sides, and are located beside the B6318 Military Road. Like Milecastles 9, 23, 25, and 51, a ditch has been identified around the Milecastle, and is still visible to a small extent. It has been postulated that this was as a result of the need for drainage on the site.

Milecastle 43 (Great Chesters) was a milecastle on Hadrian's Wall (grid reference NY70356684). It was obliterated when the fort at Great Chesters (Aesica) was built.

Milecastle 59 (Old Wall) was a milecastle on Hadrian's Wall (grid reference NY48546174).

Milecastle 65 (Tarraby) was a milecastle on Hadrian's Wall (grid reference NY40855793).