Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine is a vaccine primarily used against tuberculosis (TB). It is named after its inventors Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin. In countries where tuberculosis or leprosy is common, one dose is recommended in healthy babies as soon after birth as possible. In areas where tuberculosis is not common, only children at high risk are typically immunized, while suspected cases of tuberculosis are individually tested for and treated. Adults who do not have tuberculosis and have not been previously immunized, but are frequently exposed, may be immunized, as well. BCG also has some effectiveness against Buruli ulcer infection and other nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Additionally, it is sometimes used as part of the treatment of bladder cancer.

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating the body's adaptive immunity, they help prevent sickness from an infectious disease. When a sufficiently large percentage of a population has been vaccinated, herd immunity results. Herd immunity protects those who may be immunocompromised and cannot get a vaccine because even a weakened version would harm them. The effectiveness of vaccination has been widely studied and verified. Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases; widespread immunity due to vaccination is largely responsible for the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the elimination of diseases such as polio and tetanus from much of the world. However, some diseases, such as measles outbreaks in America, have seen rising cases due to relatively low vaccination rates in the 2010s – attributed, in part, to vaccine hesitancy.

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins. The agent stimulates the body's immune system to recognize the agent as a threat, destroy it, and to further recognize and destroy any of the microorganisms associated with that agent that it may encounter in the future. Vaccines can be prophylactic, or therapeutic. Some vaccines offer full sterilizing immunity, in which infection is prevented completely.

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The skin form presents with a small blister with surrounding swelling that often turns into a painless ulcer with a black center. The inhalation form presents with fever, chest pain and shortness of breath. The intestinal form presents with diarrhea, abdominal pains, nausea and vomiting. The injection form presents with fever and an abscess at the site of drug injection.

The smallpox vaccine is the first vaccine to be developed against a contagious disease. In 1796, the British doctor Edward Jenner demonstrated that an infection with the relatively mild cowpox virus conferred immunity against the deadly smallpox virus. Cowpox served as a natural vaccine until the modern smallpox vaccine emerged in the 20th century. From 1958 to 1977, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a global vaccination campaign that eradicated smallpox, making it the only human disease to be eradicated. Although routine smallpox vaccination is no longer performed on the general public, the vaccine is still being produced to guard against bioterrorism, biological warfare, and monkeypox.

Polio vaccines are vaccines used to prevent poliomyelitis (polio). Two types are used: an inactivated poliovirus given by injection (IPV) and a weakened poliovirus given by mouth (OPV). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends all children be fully vaccinated against polio. The two vaccines have eliminated polio from most of the world, and reduced the number of cases reported each year from an estimated 350,000 in 1988 to 33 in 2018.

Immunization, or immunisation, is the process by which an individual's immune system becomes fortified against an infectious agent.

In biology, immunity is the capability of multicellular organisms to resist harmful microorganisms. Immunity involves both specific and nonspecific components. The nonspecific components act as barriers or eliminators of a wide range of pathogens irrespective of their antigenic make-up. Other components of the immune system adapt themselves to each new disease encountered and can generate pathogen-specific immunity.

The Ames strain is one of 89 known strains of the anthrax bacterium. It was isolated from a diseased 14-month-old Beefmaster heifer that died in Sarita, Texas in 1981. The strain was isolated at the Texas Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory and a sample was sent to the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). Researchers at USAMRIID mistakenly believed the strain came from Ames, Iowa because the return address on the package was the USDA's National Veterinary Services Laboratories in Ames and mislabeled the specimen.

Artificial induction of immunity is immunization achieved by human efforts in preventive healthcare, as opposed to natural immunity as produced by organisms' immune systems. It makes people immune to specific diseases by means other than waiting for them to catch the disease. The purpose is to reduce the risk of death and suffering, that is, the disease burden, even when eradication of the disease is not possible. Vaccination is the chief type of such immunization, greatly reducing the burden of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Mumps vaccines are vaccines which prevent mumps. When given to a majority of the population they decrease complications at the population level. Effectiveness when 90% of a population is vaccinated is estimated at 85%. Two doses are required for long term prevention. The initial dose is recommended between 12 and 18 months of age. The second dose is then typically given between two years and six years of age. Usage after exposure in those not already immune may be useful.

The Anthrax Vaccine Immunization Program (AVIP), is the name of the policy set forth by the U.S. federal government to immunize its military and certain civilian personnel with the BioThrax anthrax vaccine. It began in earnest in 1997 by the Clinton administration. Thereafter it ran into Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and judicial obstacles. Over 8 million doses of BioThrax were administered to over 2 million U.S. military personnel as part of the program between March 1998 and June 2008.

A zoster vaccine is a vaccine that reduces the incidence of herpes zoster (shingles), a disease caused by reactivation of the varicella zoster virus, which is also responsible for chickenpox. Shingles provokes a painful rash with blisters, and can be followed by chronic pain, as well as other complications. Older people are more often affected, as are people with weakened immune systems (immunosuppression). Both shingles and postherpetic neuralgia can be prevented by vaccination.

Varicella vaccine, also known as chickenpox vaccine, is a vaccine that protects against chickenpox. One dose of vaccine prevents 95% of moderate disease and 100% of severe disease. Two doses of vaccine are more effective than one. If given to those who are not immune within five days of exposure to chickenpox it prevents most cases of disease. Vaccinating a large portion of the population also protects those who are not vaccinated. It is given by injection just under the skin. Another vaccine, known as zoster vaccine, is used to prevent diseases caused by the same virus - the varicella zoster virus.

An attenuated vaccine is a vaccine created by reducing the virulence of a pathogen, but still keeping it viable. Attenuation takes an infectious agent and alters it so that it becomes harmless or less virulent. These vaccines contrast to those produced by "killing" the virus.

Hepatitis A vaccine is a vaccine that prevents hepatitis A. It is effective in around 95% of cases and lasts for at least twenty years and possibly a person's entire life. If given, two doses are recommended beginning after the age of one. It is given by injection into a muscle. The first hepatitis A vaccine was approved in Europe in 1991, and the United States in 1995. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.

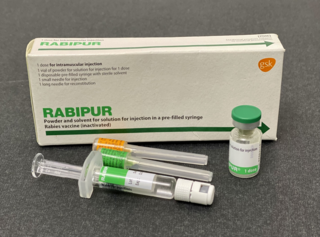

The rabies vaccine is a vaccine used to prevent rabies. There are a number of rabies vaccines available that are both safe and effective. They can be used to prevent rabies before, and, for a period of time, after exposure to the rabies virus, which is commonly caused by a dog bite or a bat bite.

Bacillus anthracis is a Gram-positive and rod-shaped bacterium that causes anthrax, a deadly disease to livestock and, occasionally, to humans. It is the only permanent (obligate) pathogen within the genus Bacillus. Its infection is a type of zoonosis, as it is transmitted from animals to humans. It was discovered by a German physician Robert Koch in 1876, and became the first bacterium to be experimentally shown as a pathogen. The discovery was also the first scientific evidence for the germ theory of diseases.

Anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA) is the only FDA-licensed human anthrax vaccine in the United States. It is produced under the trade name BioThrax by the Emergent BioDefense Corporation in Lansing, Michigan. The parent company of Emergent BioDefense is Emergent BioSolutions of Rockville, Maryland. It is sometimes called MDPH-PA or MDPH-AVA after the former Michigan Department of Public Health, which formerly was involved in its production.

Dengue vaccine is a vaccine used to prevent dengue fever in humans. Development of dengue vaccines began in the 1920s, but was hindered by the need to create immunity against all four dengue serotypes.