Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation worldwide, although these laws do not consider all work by children as child labour; exceptions include work by child artists, family duties, supervised training, and some forms of work undertaken by Amish children, as well as by Indigenous children in the Americas.

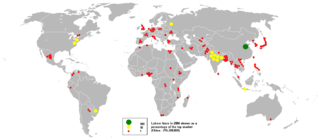

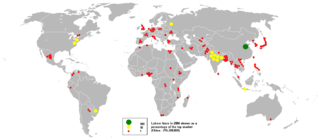

In macroeconomics, the labor force is the sum of those either working or looking for work :

A double burden is the workload of people who work to earn money, but who are also responsible for significant amounts of unpaid domestic labor. This phenomenon is also known as the Second Shift as in Arlie Hochschild's book of the same name. In couples where both partners have paid jobs, women often spend significantly more time than men on household chores and caring work, such as childrearing or caring for sick family members. This outcome is determined in large part by traditional gender roles that have been accepted by society over time. Labor market constraints also play a role in determining who does the bulk of unpaid work.

Child labour in Botswana is defined as the exploitation of children through any form of work which is harmful to their physical, mental, social and moral development. Child labour in Botswana is characterised by the type of forced work at an associated age, as a result of reasons such as poverty and household-resource allocations. Child labour in Botswana is not of higher percentage according to studies. The United States Department of Labor states that due to the gaps in the national frameworks, scarce economy, and lack of initiatives, “children in Botswana engage in the worst forms of child labour”. The International Labour Organization is a body of the United Nations which engages to develop labour policies and promote social justice issues. The International Labour Organization (ILO) in convention 138 states the minimum required age for employment to act as the method for "effective abolition of child labour" through establishing minimum age requirements and policies for countries when ratified. Botswana ratified the Minimum Age Convention in 1995, establishing a national policy allowing children at least fourteen-years old to work in specified conditions. Botswana further ratified the ILO's Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, convention 182, in 2000.

Child labour in Eswatini is a controversial issue that affects a large portion of the country's population. Child labour is often seen as a human rights concern because it is "work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, and that is harmful to physical and mental development," as defined by the International Labour Organization (ILO). Additionally, child labour is harmful in that it restricts a child's ability to attend school or receive an education. The ILO recognizes that not all forms of children working are harmful, but this article will focus on the type of child labour that is generally accepted as harmful to the child involved.

Child Workers in Nepal (CWIN) is a non-governmental organization working as an advocate for children's rights. CWIN supports street children, children subjected to child labour, children who are sexually exploited, and also those victimized by violence. The organization's objective is to protect the rights of children in Nepal. It was established in 1987 by a group of students at Tribhuvan University who, upon investigating the conditions of children living on the streets in Kathmandu, Nepal, recognized the need for advocacy in this area. As a "watchdog" in the field of child rights in Nepal, CWIN acts as a voice for the disadvantaged and exploited children. It does this by lobbying, campaigning, and pressuring the government to protect and promote children's rights, and to end exploitation, abuse and discrimination against children.

Labour in India refers to employment in the economy of India. In 2020, there were around 476.67 million workers in India, the second largest after China. Out of which, agriculture industry consist of 41.19%, industry sector consist of 26.18% and service sector consist 32.33% of total labour force. Of these over 94 percent work in unincorporated, unorganised enterprises ranging from pushcart vendors to home-based diamond and gem polishing operations. The organised sector includes workers employed by the government, state-owned enterprises and private sector enterprises. In 2008, the organised sector employed 27.5 million workers, of which 17.3 million worked for government or government owned entities.

The status of women in Nepal has varied throughout history. In the early 1990s, like in some other Asian countries, women in Nepal were generally subordinate to men in virtually every aspect of life. Historically, Nepal has been a predominantly patriarchal society where women are generally subordinate to men. Men were considered to be the leader of the family and superior to women. Also, social norms and values were biased in favor of men. This strong bias in favor of sons in society meant that daughters were discriminated against from birth and did not have equal opportunities to achieve all aspects of development. Daughters were deprived of many privileges, including rights, education, healthcare, parental property rights, social status, last rites of dead parents, and were thought to be other's property and liabilities. In the past century, there has been a dramatic positive change in the role and status of women in Nepal, reducing gender inequality. While the 1990 Constitution guaranteed fundamental rights to all citizens without discrimination on the basis of ethnicity, caste, religion, or sex, the modernization of society, along with increased education of the general population, have also played an important role in promoting gender equality. The roles of women have changed in various ways in the modern Nepalese society.

Child labour in Bangladesh is significant, with 4.7 million children aged 5 to 14 in the work force in 2002-03. Out of the child labourers engaged in the work force, 83% are employed in rural areas and 17% are employed in urban areas. Child labour can be found in agriculture, poultry breeding, fish processing, the garment sector and the leather industry, as well as in shoe production. Children are involved in jute processing, the production of candles, soap and furniture. They work in the salt industry, the production of asbestos, bitumen, tiles and ship breaking.

A significant proportion of children in India are engaged in child labour. In 2011, the national census of India found that the total number of child labourers, aged [5–14], to be at 10.12 million, out of the total of 259.64 million children in that age group. The child labour problem is not unique to India; worldwide, about 217 million children work, many full-time.

Human trafficking in Nepal is a growing criminal industry affecting multiple other countries beyond Nepal, primarily across Asia and the Middle East. Nepal is mainly a source country for men, women and children subjected to the forced labor and sex trafficking. U.S. State Department's Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons placed the country in "Tier 2" in 2017.

Child labour in Pakistan is the employment of children to work in Pakistan, which causes them mental, physical, moral and social harm. Child labour takes away the education from children. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan estimated that in the 1990s, 11 million children were working in the country, half of whom were under age ten. In 1996, the median age for a child entering the work force was seven, down from eight in 1994. It was estimated that one quarter of the country's work force was made up of children. Child labor stands out as a significant issue in Pakistan, primarily driven by poverty. The prevalence of poverty in the country has compelled children to engage in labor, as it has become necessary for their families to meet their desired household income level, enabling them to afford basic necessities like butter and bread.

Child labour refers to the full-time employment of children under a minimum legal age. In 2003, an International Labour Organization (ILO) survey reported that one in every ten children in the capital above the age of seven was engaged in child domestic labour. Children who are too young to work in the fields work as scavengers. They spend their days rummaging in dumps looking for items that can be sold for money. Children also often work in the garment and textile industry, in prostitution, and in the military.

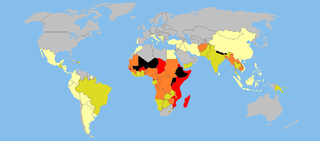

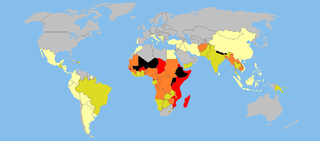

Child labour in Africa is generally defined based on two factors: type of work and minimum appropriate age of the work. If a child is involved in an activity that is harmful to his/her physical and mental development, he/she is generally considered as a child labourer. That is, any work that is mentally, physically, socially or morally dangerous and harmful to children, and interferes with their schooling by depriving them of the opportunity to attend school or requiring them to attempt to combine school attendance with excessively long and heavy work. Appropriate minimum age for each work depends on the effects of the work on the physical health and mental development of children. ILO Convention No. 138 suggests the following minimum age for admission to employment under which, if a child works, he/she is considered as a child laborer: 18 years old for hazardous works, and 13–15 years old for light works, although 12–14 years old may be permitted for light works under strict conditions in very poor countries. Another definition proposed by ILO's Statistical Information and Monitoring Program on Child Labor (SIMPOC) defines a child as a child labourer if he/she is involved in an economic activity, and is under 12 years old and works one or more hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least 14 hours per week, or is 14 years old or under and works at least one hour per week in activities that are hazardous, or is 17 or under and works in an "unconditional worst form of child labor".

Child labour in Nigeria is the employment of children under the age of 18 in a manner that restricts or prevents them from basic education and development. Child labour is pervasive in every state of the country. In 2006, the number of child workers was estimated at about 15 million. Poverty is a major factor that drives child labour in Nigeria. In poor families, child labour is a major source of income for the family.

Nepal, a Himalayan country situated in South Asia, is one of the poor country because of undeveloped resources. It has suffered from political instability and has had undemocratic rule for much of its history. There is a lack of access to basic facilities, people have superstitious beliefs, and there are high levels of gender discrimination. Although the Constitution provides for protection of women, including equal pay for equal work, the Government has not taken significant action to implement its provisions.

Child labor in Bolivia is a widespread phenomenon. A 2014 document on the worst forms of child labor released by the U.S. Department of Labor estimated that approximately 20.2% of children between the ages of 7 and 14, or 388,541 children make up the labor force in Bolivia. Indigenous children are more likely to be engaged in labor than children who reside in urban areas. The activities of child laborers are diverse, however the majority of child laborers are involved in agricultural labor, and this activity varies between urban and rural areas. Bolivia has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1990. Bolivia has also ratified the International Labour Organization’s Minimum Age Convention, 1973 (138) and the ILO’s worst forms of child labor convention (182). In July 2014, the Bolivian government passed the new child and adolescent code, which lowered the minimum working age to ten years old given certain working conditions The new code stipulates that children between the ages of ten and twelve can legally work given they are self-employed while children between 12 and 14 may work as contracted laborers as long as their work does not interfere with their education and they work under parental supervision.

Gender inequality in Nepal refers to disparities and inequalities between men and women in Nepal, a landlocked country in South Asia. Gender inequality is defined as unequal treatment and opportunities due to perceived differences based solely on issues of gender. Gender inequality is a major barrier for human development worldwide as gender is a determinant for the basis of discrimination in various spheres such as health, education, political representation, and labor markets. Although Nepal is modernizing and gender roles are changing, the traditionally patriarchal society creates systematic barriers to gender equality.

Child Labor in Saudi Arabia is the employing of children for work that deprives children of their childhood, dignity, potential, and that is harmful to a child’s physical and mental development.

Nepal has a labour force of 16.8-million-workers, the 37th largest in the world as of 2017. Although agriculture makes up only about 28 per cent of Nepal's GDP, it employs more than two-thirds of the workforce. Millions of men work as unskilled labourers in foreign countries, leaving the household, agriculture, and raising of children to women alone. Most of the working-age women are employed in agricultural sector, contributions to which are usually ignored or undervalued in official statistics. Few women who are employed in the formal sectors face discrimination and significant wage gap. Almost half of all children are economically active, half of which are child labourers. Millions of people, men, women and children of both sexes, are employed as bonded labourers, in slavery-like conditions. Trade unions have played a significant role in earning better working conditions and workers' rights, both at the company level and the national government level. Worker-friendly labour laws, endorsed by the labour unions as well as business owners, provide a framework for better working conditions and secure future for the employees, but their implementation is severely lacking in practice. Among the highly educated, there is a significant brain-drain, posing a significant hurdle in fulfilling the demand for skilled workforce in the country.