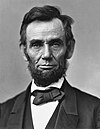

Abraham Lincoln was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the Union through the American Civil War to defend the nation as a constitutional union and succeeded in defeating the insurgent Confederacy, abolishing slavery, expanding the power of the federal government, and modernizing the U.S. economy.

The American Civil War was a civil war in the United States between the Union and the Confederacy, which had been formed by states that had seceded from the Union. The cause of the war was the dispute over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prevented from doing so, which many believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the effect of changing the legal status of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as slaves escaped the control of their enslavers, either by fleeing to Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, they were permanently free. In addition, the Proclamation allowed for former slaves to "be received into the armed service of the United States". The Emancipation Proclamation was a significant part of the end of slavery in the United States.

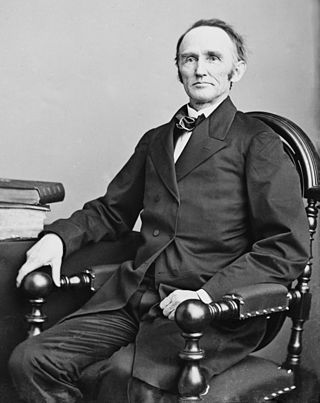

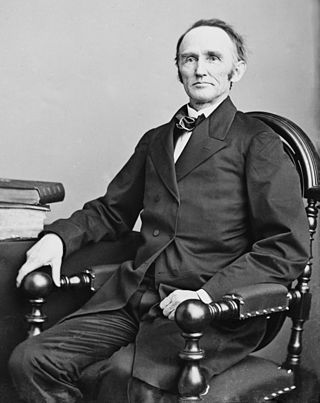

Montgomery Blair was an American politician and lawyer from Maryland. He served in the Lincoln administration cabinet as Postmaster-General from 1861 to 1864, during the Civil War. He was the son of Francis Preston Blair, elder brother of Francis Preston Blair Jr. and cousin of B. Gratz Brown.

Edward Bates was an American lawyer, politician and judge. He represented Missouri in the US House of Representatives and served as the U.S. Attorney General under President Abraham Lincoln. A member of the influential Bates family, he was the first US Cabinet appointee from a state west of the Mississippi River.

Abraham Lincoln's position on slavery in the United States is one of the most discussed aspects of his life. Lincoln frequently expressed his moral opposition to slavery in public and private. "I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong," he stated. "I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel." However, the question of what to do about it and how to end it, given that it was so firmly embedded in the nation's constitutional framework and in the economy of much of the country, was complex and politically challenging. In addition, there was the unanswered question, which Lincoln had to deal with, of what would become of the four million slaves if liberated: how they would earn a living in a society that had almost always rejected them or looked down on their very presence.

The 37th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C., from March 4, 1861, to March 4, 1863, during the first two years of Abraham Lincoln's presidency. The apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives was based on the 1850 United States census.

Francis Bicknell Carpenter was an American painter born in Homer, New York. Carpenter is best known for his painting First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln, which is hanging in the United States Capitol. Carpenter resided with President Lincoln at the White House and in 1866 published his one-volume memoir Six Months at the White House with Abraham Lincoln. Carpenter was a descendant of the New England Rehoboth Carpenter family.

The presidency of Abraham Lincoln began on March 4, 1861, when Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the 16th president of the United States, and ended upon his assassination and death on April 15, 1865, 42 days into his second term. Lincoln was the first member of the recently established Republican Party elected to the presidency. Lincoln successfully presided over the Union victory in the American Civil War, which dominated his presidency and resulted in the end of slavery.

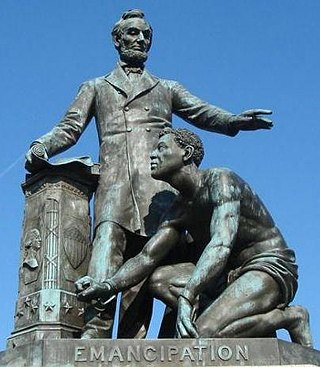

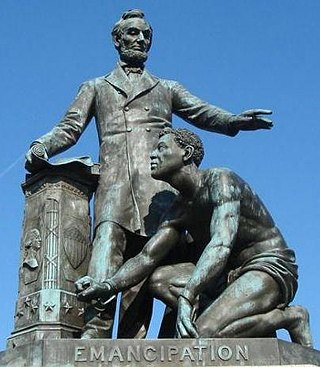

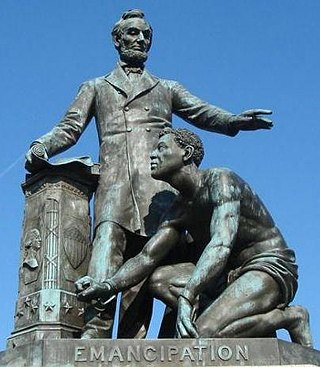

The Emancipation Memorial, also known as the Freedman's Memorial or the Emancipation Group is a monument in Lincoln Park in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D.C. It was sometimes referred to as the "Lincoln Memorial" before the more prominent so-named memorial was dedicated in 1922.

Harold Holzer is a scholar of Abraham Lincoln and the political culture of the American Civil War Era. He serves as director of Hunter College's Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute. Holzer previously spent twenty-three years as senior vice president for public affairs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York before retiring in 2015.

This bibliography of Abraham Lincoln is a comprehensive list of written and published works about or by Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States. In terms of primary sources containing Lincoln's letters and writings, scholars rely on The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, edited by Roy Basler, and others. It only includes writings by Lincoln, and omits incoming correspondence. In the six decades since Basler completed his work, some new documents written by Lincoln have been discovered. Previously, a project was underway at the Papers of Abraham Lincoln to provide "a freely accessible comprehensive electronic edition of documents written by and to Abraham Lincoln". The Papers of Abraham Lincoln completed Series I of their project The Law Practice of Abraham Lincoln in 2000. They electronically launched The Law Practice of Abraham Lincoln, Second Edition in 2009, and published a selective print edition of this series. Attempts are still being made to transcribe documents for Series II and Series III.

An Act for the Release of certain Persons held to Service or Labor in the District of Columbia, 37th Cong., Sess. 2, ch. 54, 12 Stat. 376, known colloquially as the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act or simply Compensated Emancipation Act, was a law that ended slavery in the District of Columbia, while providing slave owners who remained loyal to the United States in the then-ongoing Civil War to petition for compensation. Although not written by him, the act was signed by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln on April 16, 1862. April 16 is now celebrated in the city as Emancipation Day.

The Second Emancipation Proclamation is the term applied to an envisioned executive order that Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement called on President John F. Kennedy to issue. As the Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order issued by President Abraham Lincoln to free all slaves being held in states at war with the Union, the envisioned "Second Emancipation Proclamation" was to use the powers of the executive office to strike a severe blow to segregation.

Edward Dalton Marchant (1806-1887), also known as Edward D. Marchant and E. D. Marchant, was an American artist. He was born in Edgartown, Massachusetts in 1806. Largely self-taught, Marchant began his career as a house painter, establishing a portrait studio in Edgartown by the mid-1820s.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Abraham Lincoln:

This article documents the political career of Abraham Lincoln from the end of his term in the United States House of Representatives in March 1849 to the beginning of his first term as President of the United States in March 1861.

The presidential transition of Abraham Lincoln began when he won the United States 1860 United States presidential election, becoming the president-elect of the United States, and ended when Lincoln was inaugurated at noon on March 4, 1861.

In the District of Columbia, the slave trade was legal from its creation until it was outlawed as part of the Compromise of 1850. That restrictions on slavery in the District were probably coming was a major factor in the retrocession of the Virginia part of the District back to Virginia in 1847. Thus the large slave-trading businesses in Alexandria, such as Franklin & Armfield, could continue their operations in Virginia, where slavery was more secure.

From the late-18th to the mid-19th century, various states of the United States of America allowed the enslavement of human beings, most of whom had been transported from Africa during the Atlantic slave trade or were their descendants. The institution of slavery was established in North America in the 16th century under Spanish colonization, British colonization, French colonization, and Dutch colonization.