A loom is a device used to weave cloth and tapestry. The basic purpose of any loom is to hold the warp threads under tension to facilitate the interweaving of the weft threads. The precise shape of the loom and its mechanics may vary, but the basic function is the same.

A power loom is a mechanized loom, and was one of the key developments in the industrialization of weaving during the early Industrial Revolution. The first power loom was designed and patented in 1785 by Edmund Cartwright. It was refined over the next 47 years until a design by the Howard and Bullough company made the operation completely automatic. This device was designed in 1834 by James Bullough and William Kenworthy, and was named the Lancashire loom.

A cotton mill is a building that houses spinning or weaving machinery for the production of yarn or cloth from cotton, an important product during the Industrial Revolution in the development of the factory system.

Barrowford is a village and civil parish in the Pendle district of Lancashire, England, north of Nelson, near the Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Four Loom Weaver, probably derived from "The Poor Cotton Weaver" is a 19th-century English lament on starvation. One source also names it Jone o Grinfilt though this title usually refers to different lyrics and score, which is about the naiveté of country folk. Actually, it is very similar to Jone o'Grinfilt Junior which can be found in John Harland's Ballads and Songs of Lancashire. Jone o Grinfilt is believed to have been written by Joseph Lees of Glodwick, near Oldham in the 1790s.

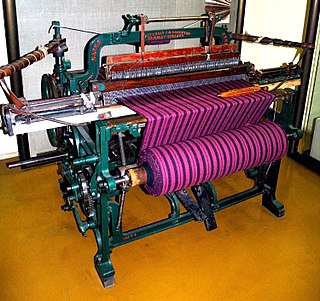

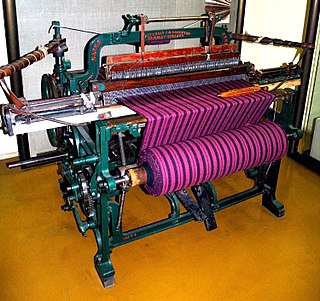

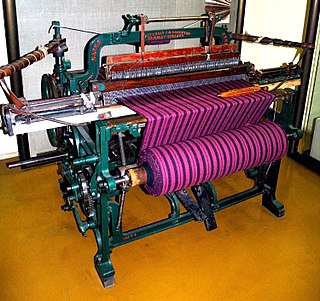

The Hattersley loom was developed by George Hattersley and Sons of Keighley, West Yorkshire, England. The company had been started by Richard Hattersley after 1784, with his son, George Hattersley, later entering the business alongside him. The company developed a number of innovative looms, of which the Hattersley Standard Loom – developed in 1921 – was a great success.

A weavers' cottage was a type of house used by weavers for cloth production in the putting-out system sometimes known as the domestic system.

The Lancashire Loom was a semi-automatic power loom invented by James Bullough and William Kenworthy in 1842. Although it is self-acting, it has to be stopped to recharge empty shuttles. It was the mainstay of the Lancashire cotton industry for a century.

Haggate is a small village within the parish of Briercliffe, situated three miles north of Burnley, Lancashire. The village is mostly built around a small crossroads, with routes towards Burnley, Nelson and Todmorden. The first buildings in the village date from the 16th century, when the Hare and Hounds public house, which still stands to this day, was built. The village was first officially documented in the 17th century. The origins of the name Haggate are unclear, although it is thought that it could mean, "the path by the hawthorn trees". The village itself is situated at the top of a hill, 800 feet above sea level. The buildings in the village are predominantly stone-built.

The Weavers' Triangle is an area of Burnley in Lancashire, England consisting mostly of 19th-century industrial buildings at the western side of town centre clustered around the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. The area has significant historic interest as the cotton mills and associated buildings encapsulate the social and economic development of the town and its weaving industry. From the 1980s, the area has been the focus of major redevelopment efforts.

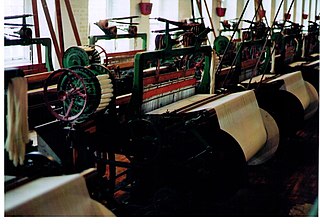

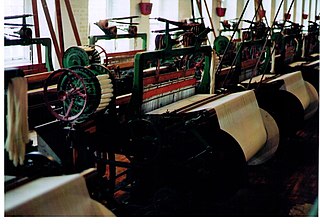

Queen Street Mill is a former weaving mill in Harle Syke, a suburb to the north-east of Burnley, Lancashire, that is a Grade I listed building. It now operates as a museum and cafe. Currently open for public tours between April and November. Over winter the café is opened on Wednesdays. It is also viewable with private bookings.

Harle Syke is a small village within the parish of Briercliffe, situated three miles north of Burnley, Lancashire, England. It was the home to eleven weaving firms, working out of seven mills. Queen Street Mill closed in 1982, and was converted to a textile museum, preserving it as a working mill. It is the world's last 19th-century steam powered weaving mill.

A weaving shed is a distinctive type of mill developed in the early 1800s in Lancashire, Derbyshire and Yorkshire to accommodate the new power looms weaving cotton, silk, woollen and worsted. A weaving shed can be a stand-alone mill, or a component of a combined mill. Power looms cause severe vibrations requiring them to be located on a solid ground floor. In the case of cotton, the weaving shed needs to remain moist. Maximum daylight is achieved, by the sawtooth "north-facing roof lights".

William Roberts and Company of Phoenix Foundry in Nelson, Lancashire, England, produced many of the steam engines that powered cotton weaving and spinning mills of Pendle and neighbouring districts. Industrial historian Mike Rothwell has called Phoenix foundry “Nelson’s most significant engineering site”.

Bancroft Shed was a weaving shed in Barnoldswick, Lancashire, England, situated on the road to Skipton. Construction was started in 1914 and the shed was commissioned in 1920 for James Nutter & Sons Limited. The mill closed on 22 December 1978 and was demolished. The engine house, chimneys and boilers have been preserved and maintained as a working steam museum. The mill was the last steam-driven weaving shed to be constructed and the last to close.

The more looms system was a productivity strategy introduced in the Lancashire cotton industry, whereby each weaver would manage a greater number of looms. It was an alternative to investing in the more productive Northrop automatic looms in the 1930s. It caused resentment, resulted in industrial action, and failed to achieve any significant cost savings.

Piece-rate lists were the ways of assessing a cotton operatives pay in Lancashire in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They started as informal agreements made by one cotton master and their operatives then each cotton town developed their own list. Spinners merged all of these into two main lists which were used by all, while weavers used one 'unified' list.

Steaming or artificial humidity was the process of injecting steam from boilers into cotton weaving sheds in Lancashire, England, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The intention was to prevent breakages in short-staple Indian Surat cotton which was introduced in 1862 during a blockade of American cotton at the time of the American Civil War. There was considerable concern about the health implications of steaming. Found to cause ill health, this practice became the subject of much campaigning and investigation from the 1880s to the 1920s. A number of Acts of Parliament imposed modifications.

A Dandy loom was a hand loom, that automatically ratcheted the take-up beam. Each time the weaver moved the sley to beat-up the weft, a rachet and pawl mechanism advanced the cloth roller. In 1802 William Ratcliffe of Stockport patented a Dandy loom with a cast-iron frame. It was this type of Dandy loom that was used in the small dandy loom shops.