Ehrlichiosis is a tick-borne disease of dogs usually caused by the rickettsial agent Ehrlichia canis. Ehrlichia canis is the pathogen of animals. Humans can become infected by E. canis and other species after tick exposure. German Shepherd Dogs are thought to be susceptible to a particularly severe form of the disease; other breeds generally have milder clinical signs. Cats can also be infected.

Colorado tick fever (CTF) is a viral infection (Coltivirus) transmitted from the bite of an infected Rocky Mountain wood tick (Dermacentor andersoni). It should not be confused with the bacterial tick-borne infection, Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Colorado tick fever is probably the same disease that American pioneers referred to as "mountain fever".

Arbovirus is an informal name for any virus that is transmitted by arthropod vectors. The term arbovirus is a portmanteau word. Tibovirus is sometimes used to more specifically describe viruses transmitted by ticks, a superorder within the arthropods. Arboviruses can affect both animals and plants. In humans, symptoms of arbovirus infection generally occur 3–15 days after exposure to the virus and last three or four days. The most common clinical features of infection are fever, headache, and malaise, but encephalitis and viral hemorrhagic fever may also occur.

Tick-borne diseases, which afflict humans and other animals, are caused by infectious agents transmitted by tick bites. They are caused by infection with a variety of pathogens, including rickettsia and other types of bacteria, viruses, and protozoa. The economic impact of tick-borne diseases is considered to be substantial in humans, and tick-borne diseases are estimated to affect ~80 % of cattle worldwide. Most of these pathogens require passage through vertebrate hosts as part of their life cycle. Tick-borne infections in humans, farm animals, and companion animals are primarily associated with wildlife animal reservoirs. Many tick-borne infections in humans involve a complex cycle between wildlife animal reservoirs and tick vectors. The survival and transmission of these tick-borne viruses are closely linked to their interactions with tick vectors and host cells. These viruses are classified into different families, including Asfarviridae, Reoviridae, Rhabdoviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Bunyaviridae, and Flaviviridae.

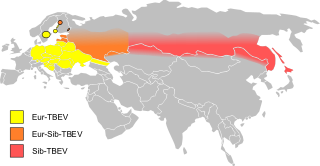

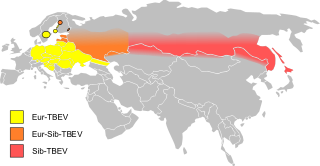

Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is a viral infectious disease involving the central nervous system. The disease most often manifests as meningitis, encephalitis or meningoencephalitis. Myelitis and spinal paralysis also occurs. In about one third of cases sequelae, predominantly cognitive dysfunction, persist for a year or more.

Phlebovirus is one of twenty genera of the family Phenuiviridae in the order Bunyavirales. The genus contains 66 species. It derives its name from Phlebotominae, the vectors of member species Naples phlebovirus, which is said to be ultimately from the Greek phlebos, meaning "vein". The proper word for "vein" in ancient Greek is however phleps (φλέψ).

Powassan virus (POWV) is a Flavivirus transmitted by ticks, found in North America and in the Russian Far East. It is named after the town of Powassan, Ontario, where it was identified in a young boy who eventually died from it. It can cause encephalitis, inflammation of the brain. No approved vaccine or antiviral drug exists. Prevention of tick bites is the best precaution.

Anaplasmosis is a tick-borne disease affecting ruminants, dogs, and horses, and is caused by Anaplasma bacteria. Anaplasmosis is an infectious but not contagious disease. Anaplasmosis can be transmitted through mechanical and biological vector processes. Anaplasmosis can also be referred to as "yellow bag" or "yellow fever" because the infected animal can develop a jaundiced look. Other signs of infection include weight loss, diarrhea, paleness of the skin, aggressive behavior, and high fever.

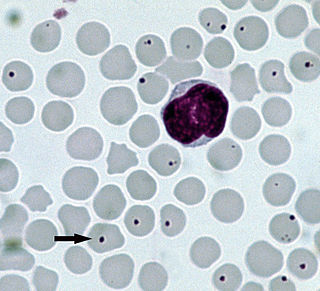

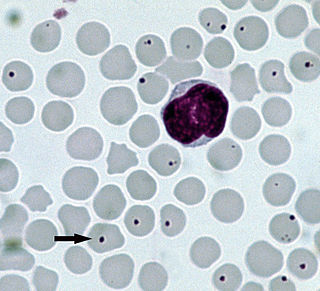

Ehrlichiosis is a tick-borne bacterial infection, caused by bacteria of the family Anaplasmataceae, genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These obligate intracellular bacteria infect and kill white blood cells.

Ixodes scapularis is commonly known as the deer tick or black-legged tick, and in some parts of the US as the bear tick. It was also named Ixodes dammini until it was shown to be the same species in 1993. It is a hard-bodied tick found in the eastern and northern Midwest of the United States as well as in southeastern Canada. It is a vector for several diseases of animals, including humans and is known as the deer tick owing to its habit of parasitizing the white-tailed deer. It is also known to parasitize mice, lizards, migratory birds, etc. especially while the tick is in the larval or nymphal stage.

Amblyomma americanum, also known as the lone star tick, the northeastern water tick, or the turkey tick, is a type of tick indigenous to much of the eastern United States and Mexico, that bites painlessly and commonly goes unnoticed, remaining attached to its host for as long as seven days until it is fully engorged with blood. It is a member of the phylum Arthropoda, class Arachnida. The adult lone star tick is sexually dimorphic, named for a silvery-white, star-shaped spot or "lone star" present near the center of the posterior portion of the adult female shield (scutum); adult males conversely have varied white streaks or spots around the margins of their shields.

Ehrlichia chaffeensis is an obligate intracellular, Gram-negative species of Rickettsiales bacteria. It is a zoonotic pathogen transmitted to humans by the lone star tick. It is the causative agent of human monocytic ehrlichiosis.

Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) is a tick-borne, infectious disease caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum, an obligate intracellular bacterium that is typically transmitted to humans by ticks of the Ixodes ricinus species complex, including Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus in North America. These ticks also transmit Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases.

Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis is a form of ehrlichiosis associated with Ehrlichia chaffeensis. This bacterium is an obligate intracellular pathogen affecting monocytes and macrophages.

Ehrlichiosis ewingii infection is an infectious disease caused by an intracellular bacteria, Ehrlichia ewingii. The infection is transmitted to humans by the tick, Amblyomma americanum. This tick can also transmit Ehrlichia chaffeensis, the bacteria that causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME).

Ehrlichia canis is an obligate intracellular bacterium that acts as the causative agent of ehrlichiosis, a disease most commonly affecting canine species. This pathogen is present throughout the United States, South America, Asia, Africa and recently in the Kimberley region of Australia. First defined in 1935, E. canis emerged in the United States in 1963 and its presence has since been found in all 48 contiguous United States. Reported primarily in dogs, E. canis has also been documented in felines and humans, where it is transferred most commonly via Rhipicephalus sanguineus, the brown dog tick.

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is a tick-borne infection caused by Dabie bandavirus also known as the SFTS virus, first reported between late March and mid-July 2009 in rural areas of Hubei and Henan provinces in Central China.

Dabie bandavirus, also called SFTS virus, is a tick-borne virus in the genus Bandavirus in the family Phenuiviridae, order Bunyavirales. The clinical condition it caused is known as severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS). SFTS is an emerging infectious disease that was first described in northeast and central China 2009 and now has also been discovered in Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan in 2015. SFTS has a fatality rate of 12% and as high as over 30% in some areas. The major clinical symptoms of SFTS are fever, vomiting, diarrhea, multiple organ failure, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia and elevated liver enzyme levels. Another outbreak occurred in East China in the early half of 2020.

Lone star bandavirus is a highly divergent bunyavirus, which is carried and transmitted by the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum. This is the same vector that transmits the SFTS virus, and the newly discovered Bhanja and Heartland viruses.

Bourbon virus is an RNA virus in the genus Thogotovirus of the family Orthomyxoviridae, which is similar to Dhori virus and Batken virus. It was first identified in 2014 in a man from Bourbon County, Kansas, United States, who died after being bitten by ticks. The case is the eighth report of human disease associated with a thogotovirus globally, and the first in the Western hemisphere. As of May 2015, a case was discovered in Stillwater, Oklahoma, and relatively little is known about the virus. No specific treatment or vaccine is available. The virus is suspected to be transmitted by ticks or insects, and avoidance of bites is recommended to reduce risk of infection. In June 2017 a 58-year-old female Missouri State Park employee died from an infection of the Bourbon virus after it had been misdiagnosed for a significant period of time.